What does the future hold for Guantanamo?

- Published

What is it like inside Guantanamo Bay?

These are uncertain times at Guantanamo Bay. Not only for the detainees but also those who guard them. After eight years in which President Obama has tried - and failed - to close the detention facility, what will President Trump mean for its future?

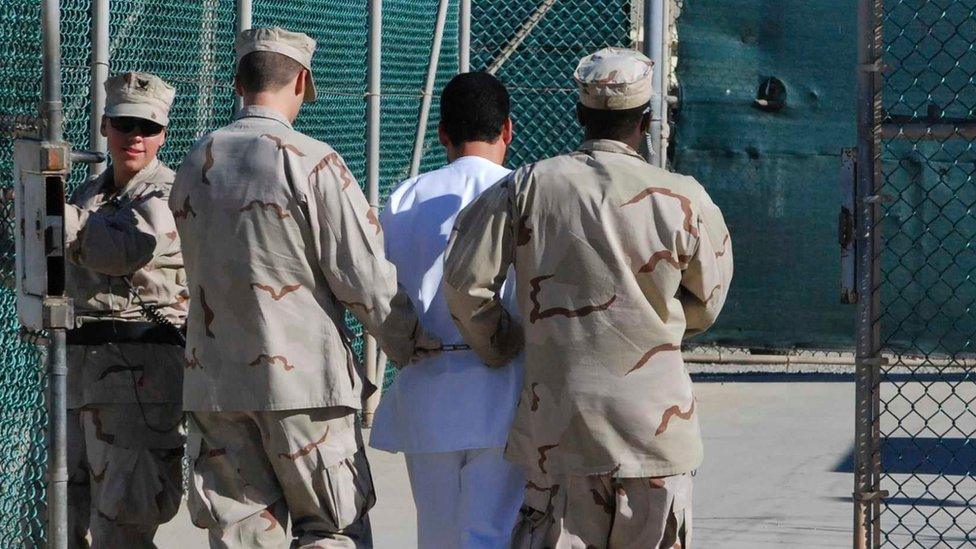

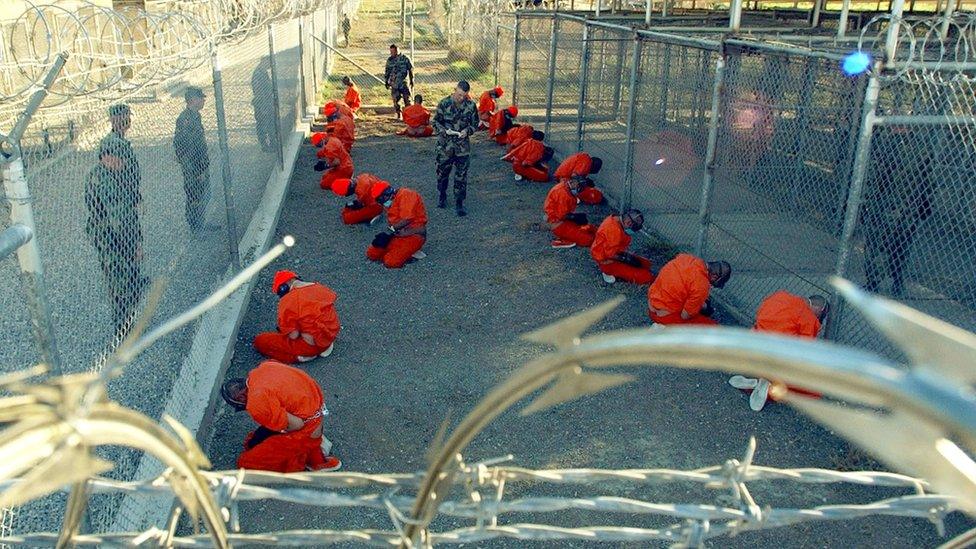

The first detainees arrived at Camp X-Ray 15 years ago in the early months of what was then called the "War on Terror". I first visited a few weeks later and watched the men in orange jumpsuits in steel cages in the hot Cuban sun.

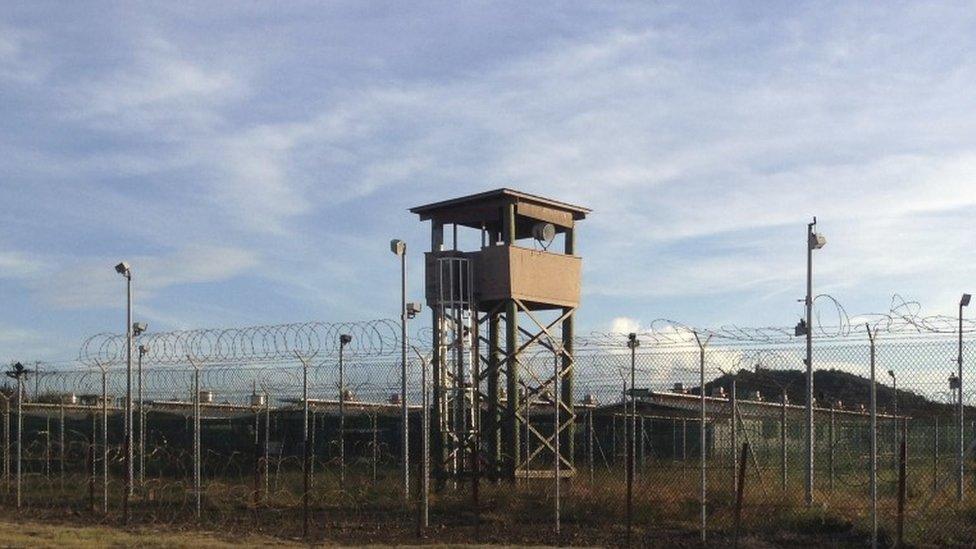

Guantanamo had been chosen partly because it was not US soil and so avoided coming under regular US law. The camp then had a thrown together feel - the Bush administration was improvising and no-one was sure how long it would last.

The orange jumpsuits worn by detainees became notorious

The next time I visited - two years later - Camp X-Ray had been replaced by the more permanent structure of Camp Delta. Guantanamo was here to stay.

Its numbers grew - around 700 at its peak. But on his second day in office eight years ago President Obama promised to close the facility, external and the pace of transfers increased.

On my visit a few weeks ago, I found much of the Camp eerily empty, a lone iguana roaming around the barbed wire. But closing Guantanamo was a promise President Obama could not keep, partly because Congress blocked the transfer of any detainees to the US.

Controlled atmosphere

Fewer than 60 men are now left. There are 20 currently cleared for release and the Obama administration is trying to transfer some of these out before its term ends.

But on 3 January, President-elect Trump made his views clear in a tweet.

"There should be no further releases," he wrote. "These are extremely dangerous people and should not be allowed back on to the battlefield."

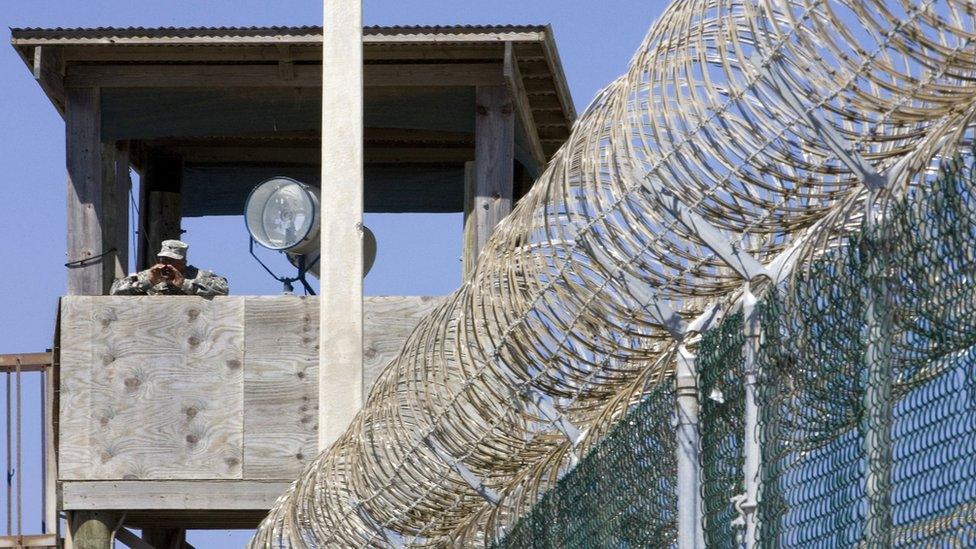

Most of the remaining detainees are held now in Camp Six.

Inside a cell in Camp Six at Guantanamo Bay

The uncertainty hanging over the base was clear as we toured the detention block. We were able to watch and film detainees in the communal areas of their cell block through one-way glass, an unsettling procedure.

The detainees are not supposed to know we are there but clearly they realised as one put up a hand-painted sign showing a question mark with a padlock underneath.

They followed the election result like everyone else and Col Steve Gabavics, Commander of the Joint Detention Force, told me: "They were all watching TV - their behaviour was pretty much the same as any other night.

"We didn't notice any significant negative response. No-one came to us angry, no-one protested. They were simply interested to see what was going to happen."

Colonel Steve Gabavics said they noticed no reaction to Donald Trump's election victory

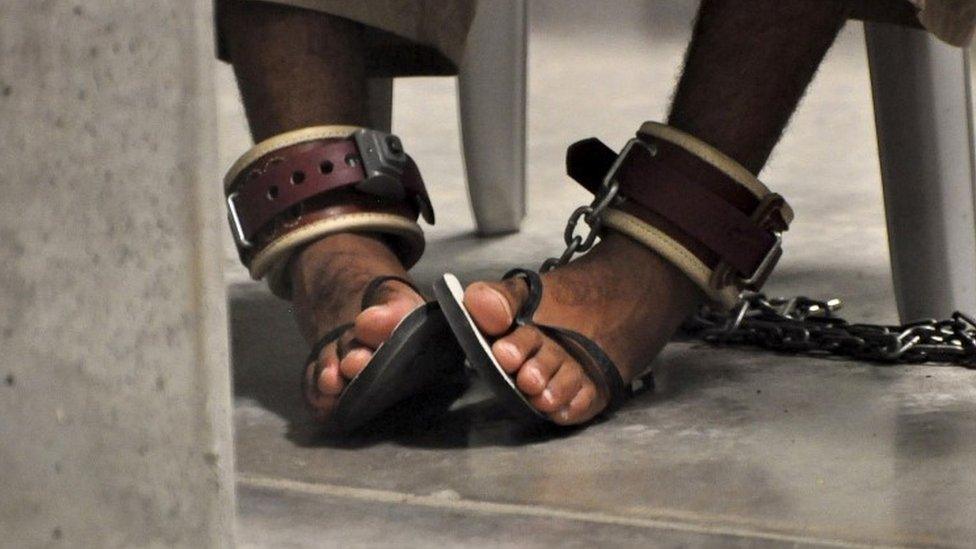

One difference from my early visits is just how much more controlled - even mundane - the interaction between detainees and guards is now compared to the early days.

The attacks of 2001 were still raw and there was a tension and sense of underlying aggression on both sides. Now, the atmosphere is much more controlled.

Detainees tap on a window to summon a guard when they have a message to pass and the guard proceeds through a door into a cage-like structure inside the cell-block where they can communicate with a detainee.

During our visit in December, officials say that the detainees were "compliant".

But what does the arrival of President Trump mean?

"You know the detainees have questions - are the transfers going to stop when the new president takes office on 20 January? We don't know, they don't know. Their lawyers may speculate, but no-one knows," says Rear Adm Peter Clarke, commander of Joint Task Force Guantanamo.

He did say - before Donald Trump's latest tweet - that "some of them may act up" if they realise they are not going to be transferred.

New detainees?

Somewhere else on the base, which sprawls across an otherwise isolated tip of Cuba, is Camp Seven. Its precise location is secret - leading to much speculation from visiting reporters.

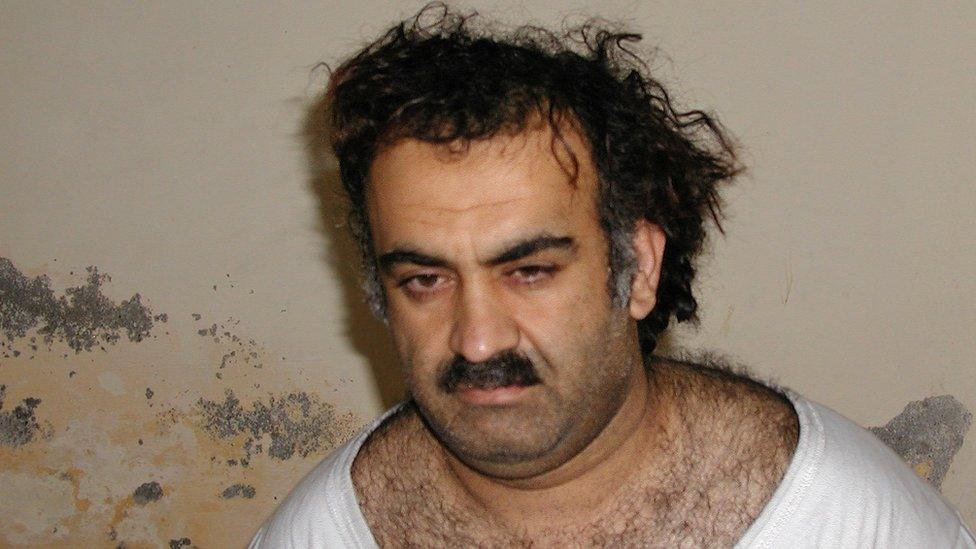

This is where so-called high value detainees are being held - men like Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the 11 September attacks who is going through the long slow process of a military commission - a form of trial.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was captured in Pakistan in March 2003 and sent to the US detention centre in Cuba in 2006

Might it be not only that transfers out are stopped, but that current detainees find they have some company?

"We are going to load it up with bad dudes," Mr Trump said in the campaign trail in February last year.

Camp Five was built to hold detainees but now sits empty. What if President Trump decides he wants to not just stop people leaving but send in new detainees?

The maximum capacity of Camp Six is around 175 detainees. Camp Five could hold 80 - it has been part-converted to a new medical facility. That means potentially Guantanamo could accommodate more than 100 extra detainees pretty much immediately. More than that would require construction work.

Officials say it is a "reasonable assumption" that they would want to segregate new detainees who would be more likely to be members of so-called Islamic State rather than al-Qaeda.

"We are prepared to receive some if that was required in the short term," Col Gabavics told us.

'Legal orders'

The Obama administration's push to close Guantanamo also meant there was a reluctance to capture more detainees in counter-terrorism operations around the world, some former officials say.

They believe that a policy of "take no prisoners" created an incentive to kill rather than capture, with the administration increasing the pace and the geographical spread of drone strikes which - on occasion - might mean useful intelligence gleaned from interrogation or captured material might be lost.

Rear Adm Peter Clarke said he is confident he will not be asked to torture detainees

Mr Trump has also said that he would consider returning to the practice of waterboarding detainees. Could that take place at Guantanamo? Rear Adm Clarke said he was "confident" that there will be no torture at Guantanamo.

"Whatever orders we receive, by the time they come to me from US Southern Command, I am confident those orders will be legal orders that I will be ready to carry out," he said.

In the 15 years since Guantanamo was opened, the contours of America's war on terror have changed.

New enemies have emerged and the question of what to do with those America is fighting - where to put them, how to treat them and even whether to kill or capture them - will now be for a new president to decide.

- Published4 January 2017

- Published3 January 2017

- Published16 August 2016

- Published30 May 2016

- Published23 February 2016