Trump and truth

- Published

This is a critical moment for journalism, particularly in the United States.

More than 40 years ago, the unmasking of the Watergate break-in inspired journalists around the world.

Reporters appeared as tireless investigators holding the most powerful to account.

Now, a new president declares the fourth estate "dishonest human beings".

A global survey published last week found only 43% of people trusted the traditional media.

Journalists find themselves on the defensive having to demonstrate their integrity to a sceptical public.

Donald Trump believes he is in a "running war" with parts of the media.

Where do Donald Trump supporters get their news from?

This struggle over who defines the facts will be a central feature of his administration.

Social media enables leaders to bypass traditional media and to talk to the public directly.

Donald Trump, with his 34,000 tweets, understands the reach and the power this gives him.

He can sit in the White House and, with a single tweet, define the news agenda of the day or distract attention away from uncomfortable news.

Some of the traditional media now accept they were instrumental in the rise of Donald Trump.

He was good for ratings.

He was the "candidate that kept on giving", as you would regularly hear in Washington.

Controversy surrounded the size of the crowd at Donald Trump's inauguration

But President Trump's rise to power was partly built on attacking the media.

At rally after rally, I watched Donald Trump point at the press pen and denounce journalists as "terrible" people, the "worst".

It was a deliberate tactic.

He wanted to define much of the media as part of the establishment elite who had ignored the plight of ordinary Americans.

He sowed the seed that journalists and their stories about him could not be trusted.

Painting journalists as untrustworthy gave him cover when he was accused of lying and exaggeration.

And so we inhabit the "post-truth world".

Democracy can't function without facts that are widely accepted.

It doesn't mean that facts shouldn't be disputed or their meaning argued over, but societies need a bedrock of information to inform their decisions.

If conspiracies and exaggerations are accepted as alternative realities, then it is much more difficult for a leader to be judged in the court of public opinion.

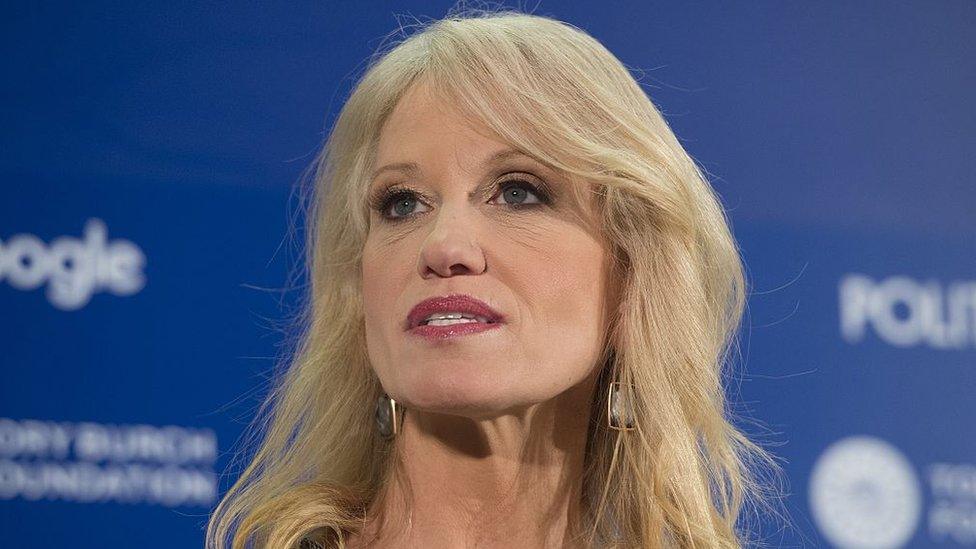

When, a few days ago, the senior White House aide Kellyanne Conway was asked why the president's press secretary had lied about the crowd size at the inauguration, she defended him by saying he was offering "alternative facts".

Kellyanne Conway used the term "alternative facts" to defend the White House press secretary

Her interviewer, Chuck Todd, of NBC, retorted that "alternative facts aren't facts, they're falsehoods".

It was an early round in the battle for the truth.

I recall an exchange I had at a Trump event where it was explained to me that the fact that a lot of people believed something gave it an element of truth.

Most Americans still get their news from TV, but more than 30% get it from the internet and particularly from Facebook.

There is now a lot of research on the role of social media in spreading false information.

In Europe, too, the reputation of the media is under fire.

Journalists have been damaged by hacking, by intrusion and the suspicion that they don't tell the whole story.

In Germany, parts of the mainstream media were accused of covering up reports of assaults on women in Cologne on New Year's Day 2016 because many of the allegations related to men believed to be migrants.

In the Edelman Trust barometer, external - published last week - trust in the media had fallen to an all-time low in 17 of the 28 countries polled.

So what is to be done?

White House press secretary Sean Spicer says the administration will "hold the press accountable"

In the United States, news organisations are grappling with difficult questions.

When should a tweet from President Trump be allowed to dominate the news agenda?

Will the cable networks have the courage to ignore a tweet?

Will the networks pursue potentially damaging stories even if it risks losing access or an interview?

One TV executive said the biggest challenge was to avoid being seen as part of the "running war" that President Trump describes.

Some organisations in the US, the UK and Germany - including the BBC - are embracing "reality checks" as part of their coverage, but they are time consuming and difficult.

Governments, too, are looking into how to boost trust in statistics and official information.

It might mean the creation of more agencies that are truly independent of government and politicians.

The new White House press secretary has said: "We are going to hold the press accountable."

It signals a battle over who defines the truth and who defines the facts.

American journalism will face one of its severest tests.

- Published23 January 2017

- Published10 September 2024