Quebec mosque shooting leaves community 'reeling'

- Published

Quebec mosque attack: 'We cannot let the racists win'

The shock from Sunday night's deadly the Quebec mosque shooting is slowly waning.

Now, the community is turning to introspection.

Questions are being raised in the province around radicalisation and whether there is a climate of intolerance that needs to be addressed.

On Monday, Alexandre Bissonette, a 27-year-old University of Laval student, was charged with six counts of first-degree murder and five counts of attempted murder.

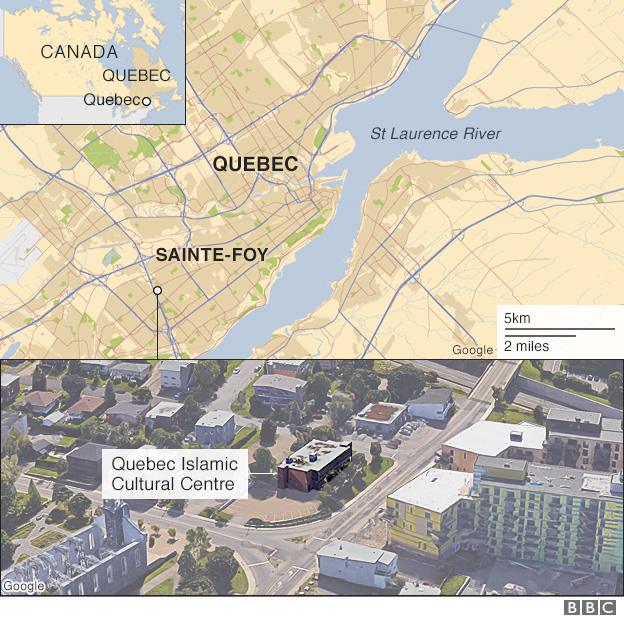

Police have not said what motivated the alleged attacker, who opened fire at the Quebec Islamic Cultural Centre during evening prayers.

Quebec attack: Who were the victims?

Quebec Muslims 'emotionally destroyed'

But there are reports that Mr Bissonette expressed anti-immigration and anti-feminist views online.

Francois Deschamps, an official with an advocacy group, Welcome to Refugees, said the suspect was known for those views online, external.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau: "They were robbed of their lives in an act of brutal violence"

Vivek Venkatesh, a professor with Montreal's Concordia University who studies online hate and radicalisation, says social media creates "echo chambers", where more extreme views can gain traction.

He says while Quebec is "still reeling" from the mosque shooting, it is important that there be a public debate in the province on how to prevent radicalisation and violent extremism in all its forms.

Pierre Martin, a political science professor with the University of Montreal, says that it appears Mr Bissonette may have been influenced by a mix of global nationalist trends, the so-called "alt-right", and "currents within Quebec itself".

Trump’s shock troops: Who are the ‘alt-right’?

In the 1960s, Quebec shifted quickly from a highly religious society to a deeply secular culture.

"People (now) tend to be critical of religion in general and how religion shapes people's social interactions," he said.

He said Quebecers tend to reject overt displays of religion.

For example, the province has debated in the past few years whether government workers should be allowed to wear clothing that showed their faith, like hijabs or turbans.

Mr Martin said the current provincial Liberal government is seen as being overly permissive on the issue while the opposition "have tended to be criticised for seizing some currents of resentment and exploiting them for political purposes".

montreal english

But he says the fact that thousands of Quebecers attended candlelight vigils on Monday showed "that the large majority of people who may have even traces of reservations about ostentatious displays of religion in the public sphere are extremely tolerant of private observance".

Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard echoed that on Tuesday, telling journalists that while "all societies live with demons and our society is not perfect", the majority of the province is open to newcomers.

Still, many in Quebec City's Muslim community have said over that past two days that they have concerns about Islamophobia in the province.

Amira Elghawaby, with the National Council of Canadian Muslims, says that in Quebec, recent debates around the niqab - like whether to ban the wearing of the face veil while offering or receiving public services - have been "toxic" and contributed to the mischaracterisation of Muslims as the "other."