Trump's Australian row: Is the US a liability for Australia?

- Published

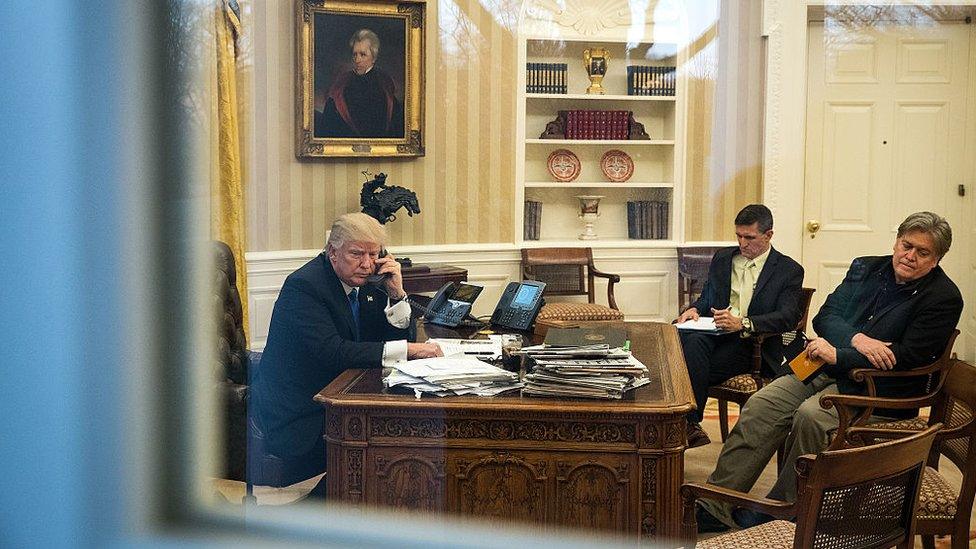

Mr Trump's phone call with Prime Minister Turnbull was described as "hostile and charged"

The airtight alliance between America and Australia took a bumpy turn on Wednesday after a "hostile and charged" phone conversation was leaked between US President Donald Trump and his Australian counterpart, Malcolm Turnbull, in which the former reportedly called it his "worst call by far, external" with a foreign leader.

Mr Trump reportedly lambasted Mr Turnbull over a deal inked by the Obama administration to resettle up to 1,250 asylum seekers in the US.

Both leaders played down the encounter, but the leak underscored a longstanding debate about whether Australia relies too much on its northern ally in matters of foreign policy and security.

For a country that is so closely aligned to the US, which bolsters its security, and so geographically important to China, which underpins its prosperity, the balance is tricky.

US-Australia refugee deal: Trump in 'worst call' with Turnbull

Dangerous ally

In his 2014 book, Dangerous Allies, external, former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser argued that while an alliance with the US may have been beneficial during the Cold War, the new reality was Australia needed to focus on establishing greater independence in the Asia-Pacific region.

Australia needed to end its "strategic dependence" on the US, he argued, because the risks of maintaining it amid the rise of China and rebalancing of world power outweighed the benefits.

Mr Fraser argued that the US alliance works against Australia's interest in the Asia-Pacific region

Mr Fraser, who was pro-American during his tenure as prime minister, changed his position over a course of his lifetime (he began as a Liberal, moved to the left and campaigned later in life for the Greens before his death in 2015).

His book was criticised for viewing China through rose-tinted glasses, failing to mention the country's territorial provocations and artificial island-building in the South China Sea.

But Mr Fraser did contend that as America's southern "linchpin", Australia would be vulnerable if the US went to war in the Pacific.

Why is the South China Sea so contentious?

The spectre of war in the Pacific seemed far-fetched as the US made its "pivot" to China, but in a Trump era of "America First", that may change.

In fact, US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson took a hard line during his confirmation hearing, stating that China should be blocked from its artificial islands, which could set the stage for a potential clash in the South China Sea.

White House chief strategist Steve Bannon has also said, external "there's no doubt" the US and China will fight a war in the next decade over the territorial disputes.

Australia's very delicate relationship with Beijing is critical to its economy; it sells coal, iron ore and other raw materials to China.

Australia has stood by the US in every war since World War One

Taken for granted

So just how entangled is Australia's security with US defence?

America has a US military base in the city of Darwin and multiple surveillance bases, including the Joint Defence Facility at Pine Gap in the Outback, while Australian Major General Richard Burr was promoted to Deputy Commander of the US Army Pacific in 2013.

The country has stood by the US in every war since World War One, and Australian forces remain in Iraq and Afghanistan, as Republican Senator John McCain noted in a statement following the revealed spat.

"Today, Australia is hosting increased deployments of US aircraft, more regular port visits by US warships, and critical training for US marines at Robertson Barracks in Darwin," he pointed out.

"This deepening co-operation is a reminder that from maintaining security and prosperity in the Asia-Pacific region to combating radical Islamist terrorism, the US-Australia relationship is more important than ever."

Unravelling a 70-year-old alliance hardly seems feasible.

Australia's annual defence budget currently stands at $32bn (£25bn). Without US support, Canberra would need raise its defence spending from about 2% of GDP to 4%, according to Peter Jennings, external, the head of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

Both countries have invested millions into the upkeep of American military bases, putting US Marines closer to Southeast Asia while also bolstering Australia's own defence.

In October, the two nations agreed to a nearly $2bn cost-sharing agreement to improve infrastructure in northern Australia, as well as pay for costs over the 25-year pact.

Foreign policy experts have argued Australia has also strengthened its diplomatic position in the region due to its American ties.

The countries also share billions of dollars in trade, which made the US Australia's second-largest trading partner in 2015, external.

But the price of American influence over Australia has not always paid off.

Mr Trump's sharp remarks are not the first time tensions have bubbled up between the two countries.

In 2015, President Obama admonished Mr Turnbull for not consulting the US about a decision to allow a Chinese company with alleged links to China's Communist Party to lease the Port of Darwin.

"Let us know next time," he reportedly told the prime minister.

Former Prime Minister John Howard once lamented he was "a little let down" that then-President Bill Clinton declined to send ground troops to support Australian military intervention in East Timor in 1999.

And Gough Whitlam famously quibbled with Richard Nixon during the Vietnam War, when the US president froze Australian access to American officials for nearly 18 months, according to University of Sydney historian James Curran.

However, the contact between the State Department and the Australian embassy continued.

A new era

Though the countries have endured previous clashes, Mr Trump's demeanour could signal that the diplomatic niceties of the past are diminishing.

"It forces us to drop romantic notions of the alliance and now be more realistic," former Australian foreign minister Bob Carr told the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper.

"It liberates leaders to say no to Washington if it seeks to recruit us for any reckless adventure," he added.

After the leaked call prompted international media frenzy, Mr Trump softened his tone.

"We have wonderful allies and we're going to keep it that way but we need to be treated fairly also," Mr Trump said of the exchange at a news conference on Thursday.

With uncertainty of a Trump administration ahead, Australia may be doing the same.