Where liberal fight goes in the age of Trump

- Published

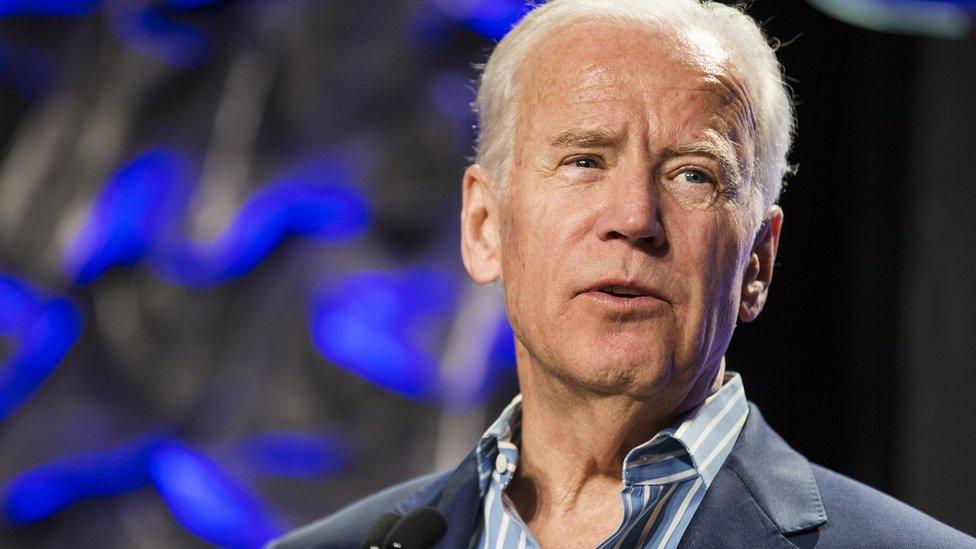

With FBI Director James Comey cancelling, former Vice-President Biden was a political highlight at the conference

In recent years, the annual South By Southwest festival in Austin, Texas, has been about more than just music, film and technology. Politics keeps seeping into the picture.

That's never been more apparent than now, with Donald Trump's presidency dominating the headlines and generating social media waves with every controversial tweet.

Former Vice President Joe Biden took the stage in Austin on Sunday afternoon looking tanned and relaxed, a man freed from the burden the Washington political pressure cooker.

In an emotional presentation, he spoke of the death of his eldest son, Beau, from cancer and his work since then to help find a cure.

The fight against cancer, Biden said, was "the only bipartisan thing left in America", and there are "a lot of decent people" in politics on both sides of the political divide who want to help.

Even while preaching bipartisanship and pledging co-operation with the new Trump administration, however, the former vice-president couldn't help but take a swipe at the current Washington power players, some of whom, he said, don't believe in global warming and the public health benefits of environmental regulation.

Joe Biden: "Some of the most innovative minds in the world are sitting in front of me"

"I shouldn't have said it that way," Mr Biden said. "But it frustrates me."

Such is this year's reality at South by Southwest.

In the time of Donald Trump, the national political climate sits like a vulture, peering over the shoulder of the largely liberal crowds who circulate among the conference's various events.

"I think that South by Southwest is always a reflection of what is happening in the larger world, and certainly we live in a very politicised time over the last three months," said Hugh Forrest, chief programming officer for the conference.

While there have been plenty of panel discussions on esoteric computer systems and lectures by technological evangelists, evidence of growing concern and, perhaps, resistance emerges.

Democratic mayors spoke of "holding the line" against Trump administration policies. Newspapers editors and social media experts discussed threats to "civil discourse in the age of a Twitterer-in-chief" and how to fight "fake news".

Civil libertarians contemplated "activism in the era of social media surveillance".

"We have in office a demagogue who makes himself feel better about himself by putting down other people," said Jim Kenney, the Democratic mayor of Philadelphia, comparing the president to a bully who can either be confronted or affirmed.

More from Anthony

Even ostensibly non-political conversations over the course of the week have been influenced by the gravitational forces emanating from Washington, DC.

"The idea that we have a serial sexual abuser and a pathological liar in that office, I can't get away from it," angel investor Chris Sacca said during an appearance on Saturday, external.

While some Republican politicians dot the panels, any sort of White House presence is absent this year. According to Forrest, no-one from the Trump team expressed interest in attending - and none were invited. Several executive branch officials were also notable late no-shows.

James Comey, the Federal Bureau of Investigations director who can't seem to avoid the national spotlight, was a scheduled high-profile guest, but he pulled out last week, citing "scheduling conflicts".

Andrey Ostrovsky, the chief medical officer for Medicaid, the US health insurance programme for the poor, also cancelled just days before he was set to talk.

Mr Ostrovsky had made national news earlier in the week when he tweeted that, unlike others at the Department of Health and Human Services, he did not support the Republican-backed plan to replace Obamacare.

"Reluctantly unable to attend," he subsequently tweeted, external, "given my recent advocacy effort." He told the BBC he still remains a "huge advocate for people served by Medicaid".

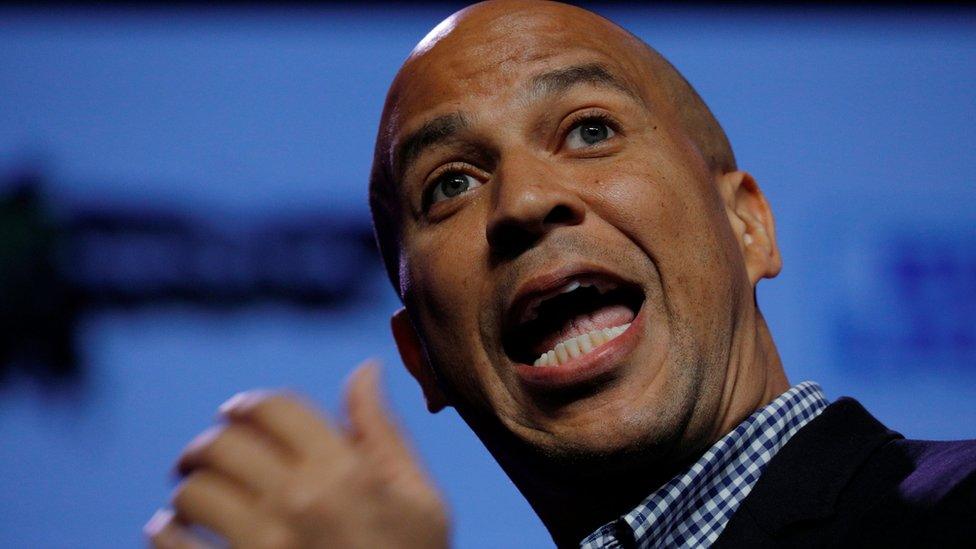

Meanwhile Democratic Senator Cory Booker - a possible 2020 presidential candidate - gave the introductory address on Friday, where he set the tone by repeatedly targeting the president and his policies.

Senator Cory Booker was among a series of liberals who spoke to the increasing political conference

"I've never seen in my lifetime an atmosphere of fear as I've seen now," Mr Booker said. "I feel a sense of pain about my country right now."

According to Forrest, it's not so much fear as it is uncertainty that is colouring the attitudes of the tech entrepreneurs, executives and activists who have crowded the convention hallways this year.

"We had a president for eight years and we generally knew what his policies were - friendly to the tech community, wanted to push start-ups," he said.

"We don't really know what the policies are for the new administration. I was naively expecting that some of these policies might have been more in place by March, but I don't think they are."

One area where there has been some certainty as to the direction Trump administration policy is heading is on immigration.

That has many in the technology industry, which relies heavily on drawing from a global talent pool, particularly concerned.

"We want more people all over the world to come here to work," says Adam Lyons, founder of the online auto insurance rate comparison service the Zebra.

"Are folks not going to want to come to the US all of a sudden or are there other places they might go? Will we still able to attract top-notch talent? That's very concerning."

"We want more people all over the world to come here to work" says chief executive Adam Lyons

Mr Lyons says while some of Mr Trump's pro-business rhetoric is exciting, workforce issues are paramount.

This is not the first year the conference, and its attendees, have grappled with pressing political concerns, of course.

Three years ago, Edward Snowden made one of his first major public appearances, via a secure video line from Moscow, warning attendees they should encrypt their email communications to avoid government observation.

Multiple panels dealt with the perceived threats of a growing surveillance state and technology's "dark arts".

In 2015, as the political world geared up for the presidential race, Chelsea Clinton spoke and prospective Republican candidate Rand Paul made the rounds, meeting with technology evangelists and opening a Texas campaign office.

Then, last year, President Barack Obama became the first sitting president to attend, offering a full-throated defence of government as a force for good.

"If there are those who despise government - oftentimes because the absence of government allows them to pollute, or keep as much money as they can, or not have to answer to consumers who are complaining about their practices - if they are controlling those who are currently in government and government gets starved of resources, then it can be a self-reinforcing notion that, in fact, government doesn't work because it's being starved," he said.

Needless to say, the current team in Washington - with its promises to "deconstruct the administrative state" - has a decidedly different view of the role of government in US society.

On Sunday Mr Biden - who told the audience he seriously considered his own presidential bid in 2016 - spoke of the important role government plays in cancer research, with a tacit acknowledgement of the new political environment.

"Your government - that many of you don't like - is the vehicle through which this gets funded," he said.

In his conclusion, the former vice-president spoke of the "urgency of now" in efforts to cure cancer.

For many of the progressives and Democratic politicians who travelled to Austin this week, however, it's hard not to look ahead, to political fights and elections to come.