Florida's Amendment 1: A cautionary tale for 2018?

- Published

As the US deals with a president who tweets stories his own staff don't believe, and an environmental chief who denies carbon emissions are the primary driver of climate change, a Florida election fight shows the ups and downs of dealing with the politics of confusion around climate and energy policy.

A few days after early voting had begun in Florida last October, an 84-year-old woman telephoned Mary Ellen Klas, the state capital bureau chief of the Miami Herald, with an urgent question.

Was there any way she could take back her vote?

Klas told the woman that wasn't going to be possible - there are no do-overs in voting.

But the woman didn't want to change her vote for president - she wanted to undo her vote on a Florida ballot measure, Amendment 1.

Amendment 1 read simply, asking voters if there should be "a right under Florida's constitution for consumers to own or lease solar equipment".

The woman on the phone had voted Yes. She, like 89% of Americans, external in a recent survey, supported expanding solar power in some way.

Florida voters were able to vote on four ballot measures in the last election

But she wanted to switch her vote because of a story Klas had just published.

A leaked recording all but confirmed what editorials in Florida papers and opponents had been arguing for months: the amendment was a deliberately misleading effort, aimed at drastically limiting solar competition.

"Your article came one day too late," she told Klas, external, vowing to tell all her friends to vote no. "I read it and I almost cried."

In 2015, a group called Floridians for Solar Choice begin petitioning for a ballot amendment that would allow state residents to set up contracts with third party companies that install solar panels for no cost and in return, sell the energy produced back to the consumer.

Across the US, utility firms see such companies as a threat, as they reduce revenues from residential consumers who are otherwise still connected to their grid.

A competing amendment by a group called Consumers for Smart Solar cropped up, titled "Rights of Electricity Consumers Regarding Solar Energy Choice". The title sounded similar and the language seemed to indicate the amendment would be broadly pro-solar, promising a right to "own or lease solar equipment".

But instead of being backed by renewable energy and environmental groups, the Smart Solar group was funded by Florida utilities.

WATCH: The world's first solar-powered airport

The issue was the second half of the utility-backed amendment: non-solar consumers would be "not required to subsidize" solar installations. Critics saw this as a way of constitutionally enshrining raised fees to make third-party solar prohibitively expensive.

"We need more solar in Florida and we need it to be done in a way that is fair, transparent and protects all consumers," said Ana Gibbs, a spokeswoman for Duke Energy, one of the major utility firms who supported Consumers for Smart Solar.

Both sides were soliciting signatures for "the solar amendment" says Josh Gillin, a reporter at the Tampa Bay Times and contributor to PolitiFact Florida. "There were reports of people saying 'Well I already signed for that'," Gillin says.

In the end, Consumers for Smart Solar got the signatures needed, and was listed on the ballot as Amendment 1. Floridians for Solar Choice admitted they would not get the required signatures in time, and began switching their efforts to organising a No campaign against Amendment 1.

Consumers for Smart Solar also won a legal battle in early 2016 challenging the amendment's wording.

In a 4-3 ruling, the Florida Supreme Court said the amendment could go forward. But one of the judges in the minority called the amendment "a wolf in sheep's clothing", writing that the ballot's title was "misleading".

Consumers for Smart Solar's Yes on 1 began their campaign in earnest - TV advertisements, direct mail and opinion pieces. Many voters received four or five pieces of mail from the group, Klas says.

They also targeted their messaging for Florida's large elderly population - claiming the amendment would protect seniors from scams, despite the amendment language guaranteeing no such thing, external. Some leaders in Florida's black and Latino communities came on board, swayed by argument that third-party solar would ultimately raise electricity rates on Florida's poorest.

Swiss researchers are looking to develop a solar panel that can push out twice the energy of existing standard roof panels

By the end of the election, Consumers for Smart Solar had raised $27m (£21m) for the campaign - $20m of that from utility companies, and the vast majority of the rest by political organisations not required to disclose their donors or coalition groups.

Floridians for Solar Choice raised about a tenth of that - $2.5m. Most of it was donated by the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy (SACE) action fund - also not required to disclose their donors - and from environmental groups, solar industry groups and several hundred individuals.

"I don't think people thought we could win," Susan Glickman, Florida Director for SACE Action Fund says. "It's a big state, lots of media markets...It's a real investment."

Meanwhile, Florida newspaper editorial boards invited both groups in to make their case.

"We really bent over backward to be as open minded as possible," says Paul Owens, opinions editor of the Orlando Sentinel. "We met with groups on both sides…for at least an hour [each]."

After the meetings, Owens' team did their own reporting and ultimately decided they would advise their readers to vote no.

"Energy seems to be an area that's changing rapidly," Owens says "We didn't think that was a good idea to lock something in a rapidly changing policy area in the constitution."

But how the amendment came to the ballot also affected their decision.

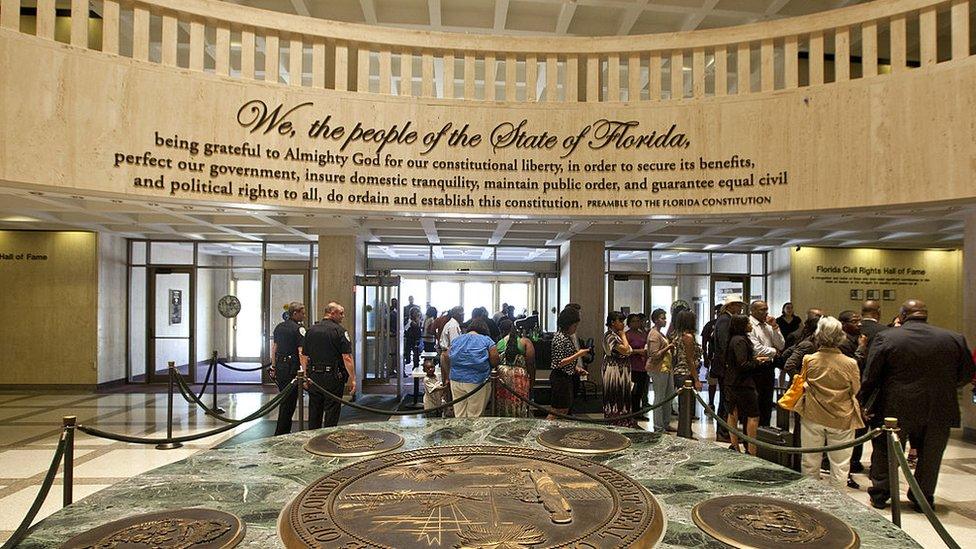

Florida's state legislature may still make changes to how solar power can be installed and sold

"The major utilities in Florida had invested so much money into this," Owens says. "Of course, they were saying they were doing it on behalf of the consumers. But," - he laughs - " we were a little sceptical."

Owens and the Sentinel eventually wrote two separate editorials opposing amendment one, and they weren't alone. More than two dozen Florida newspaper editorial boards all came out against the amendment.

When asked if the firm is concerned about being associated with what many editorials called a misleading amendment, Gibbs says Duke Energy "believes our numbers speak for themselves" and described the firm's own solar installations and projects.

Mr Lodio's children, unlike many others in the village, have solar power to do their homework by

The No on 1 campaign was losing the fundraising race, but they had an odd and energised coalition on their side - environmental groups, solar firms, Christian conservatives and Tea Party groups frustrated over state utility monopolies.

As the editorials came out, they ran with them.

"We were on radio, on debates, on Facebook Live," Glickman said. "People were emailing their list - the Christian Coalition - that's a couple hundred thousand of people."

Their language was easy to get across, Glickman says. "People understood - the only reason utilities spent [millions] was to help themselves."

A tech millionaire ran his own $100,000 internet marketing campaign against the amendment, telling Klas, external he had "nothing against power companies" but disliked "companies try to fool me".

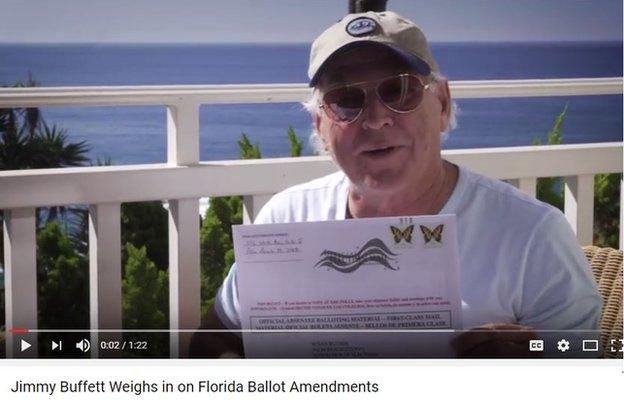

"Margaritaville" singer Jimmy Buffett recorded a video in opposition. Even Al Gore got angry about it (and got fact checked himself, external).

Jimmy Buffett endorsed the No campaign to amendment one on Youtube

In order to pass, the amendment need 60% support. But polling had showed support as high as 84% in September, external. Two weeks before the election, it had dropped - but only to 60%.

And then Klas got a scoop.

It was an audio recording of Sal Nuzzo, a policy director at James Madison Institute, a think tank hired by Consumers for Smart Solar, calling the amendment campaign "an incredibly savvy manoeuvre" that "would completely negate anything they [pro-solar interests] would try to do either legislatively or constitutionally down the road".

Nuzzo, who was speaking at a conference put on by the think tank, suggested political operatives in other states could "use a little bit of political jiu-jitsu and take what they're kind of pinning us on and use it to our benefit either in policy, in legislation or in constitutional referendums".

"As you guys look at policy in your state, or constitutional ballot initiatives in your state, remember this: solar polls very well," Nuzzo said.

The reaction to the leaked recording was quick. More editorials came out. Yes on 1 removed all references to the James Madison Institute on their website. A fire fighting union rescinded their endorsement of the amendment and demanded the group stop airing television ads featuring fire-fighters.

Scientists mobilise against 'fear of facts' in age of Trump

"It was confirming a narrative," Klas says. "It's got that 'Hey Mabel, external" quality to it - oh what's this story? I should pay attention."

And readers paid attention - and shared. "It was picked up on Facebook and recirculated," Klas says, adding reader engagement with the story made it one of the largest political stories of the year for the Herald. "People read to the end."

But without the leaked recording, would Amendment 1 have lost?

"You know, I still think we would have won," Glickman says, but "it was close".

Klas thinks it was a combination of multiple factors: an organised, if underfunded, opposition, the tape, the editorials, the drip-drip of bad news near the election.

But she's not convinced the experience will change how amendment campaigns are run.

"I think they got caught," she says.

"I think they are going to make sure they are not going to get caught again."