Sisterlocks struggle: Stylists want fewer restrictions to braid hair

- Published

Tameka Stigers working in her salon

In college, Tameka Stigers wore her hair in thin locks that looked so attractive, parents at her church wanted her to fashion their young daughters' hair.

"They said, 'Can you do it like yours?'" Stigers recalled. She wore her hair in Sisterlocks, hundreds of tiny locks that allow women with coarse, tightly-wound hair to wear almost any style - from ponytails to braids, curly or straight.

She enrolled in a short training course in order to master the technique of creating Sisterlocks - a trademarked technique - with nothing but her two hands, a comb and small elastic bands. She registered as a Sisterlock hair braider online and requests from other people in the St Louis area poured in.

To meet the demand, Stigers needed to move her business out of her home. That's where her hair braiding business hit its first snag.

Stigers knew that hair salons were regulated by the Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners, but she wasn't sure that her business, which doesn't use any chemicals, heat or scissors, would also fall under the board's purview.

She phoned the board to ask if she would have to pay upwards of £8,189 ($10,000) and spend thousands of hours in cosmetology school in order to open up a hair braiding shop. Initially, Stigers said she was told that the regulations wouldn't apply to her.

The board later reversed its course. In mid-2014, Stigers started pursuing a lawsuit against the board after it told her that she and any other hair braiders running businesses in Missouri would need to get a full cosmetology licence, which requires courses at a registered cosmetology school - courses that Stigers said don't teach any natural or African hair braiding skills at all.

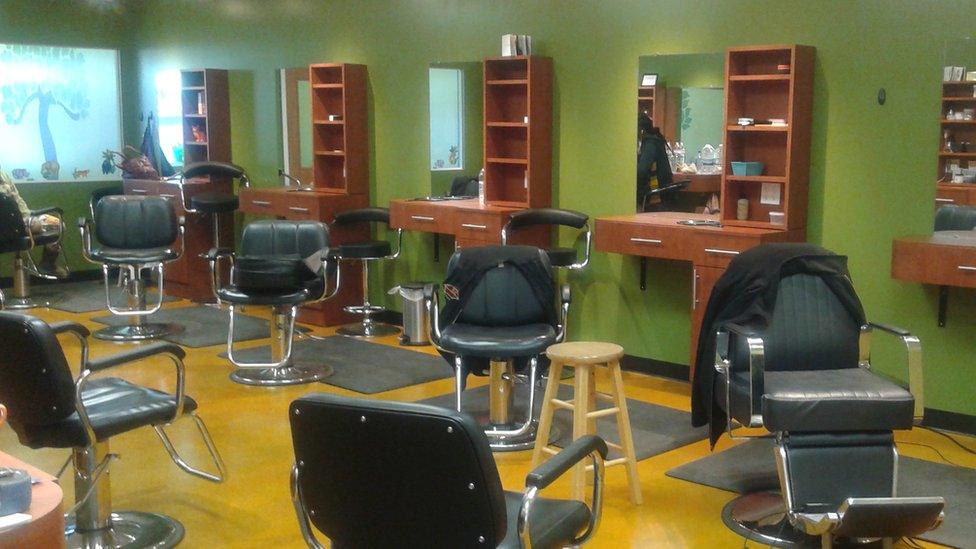

Stigers' salon has expanded

"Hair braiding is an art really," Stigers said. "It's something that if I went to cosmetology school today, I couldn't learn how to do braiding."

Stigers joined another braider, Joba Niang, in a lawsuit against the board of cosmetology and barber examiners, seeking reprieve from the regulations.

A judge ruled against Stigers in September, 2016, but her lawyers finished filing briefs to appeal the case last week, just as Stigers settled into a new, larger storefront to accommodate a growing number of customers.

Stigers didn't get a licence to braid hair, and many of her braiders lack licences, though her business partner does have a cosmetology licence to run the spa area in her new salon.

Thus far, the Missouri Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners has declined to enforce its rules while Stigers lawsuit is active, allowing Stigers and other braiders to continue working until the courts resolve the case.

If she loses, Stigers and other hair braiders will face the choice of getting the expensive cosmetology licences or closing up shop.

Women who run hair braiding salons in up to 21 states face similar regulations.

Cosmetology classes mostly focus on how to cut hair, safely dye hair, and treat hair chemically to permanently curl or straighten strands. Hair braiders don't do any of that. The small amount of training that does touch on styling typically does not go into African-style hair braiding, though a few cosmetology textbooks do nod to the techniques.

Other professional hair braiders, like Pamela Ferrell, in Washington DC have won in similar cases

The Missouri Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners does not comment on ongoing court cases, and could not discuss the regulations surrounding hair braiding. However, board members on cosmetology boards in other states have cautioned against loosening regulations because of concerns over sanitation and safety.

Jeanne Chappell, a board member on the New Hampshire Board of Barbering, Cosmetology and Esthetics told the Associated Press that diseases can be passed through the tools used during braiding and that licensing would allow the board to monitor and enforce against salons that don't use safe practices.

Pamela Ferrell, owns a braiding salon in Washington, DC, and successfully fought licensing regulations. She thinks racial biases and gaps in cultural knowledge play a role in the debate.

"It's a constant attack against our hair, our beauty standards, all under the guise of occupational licensing," Ferrell said. "It's culturally disrespectful. They're using irrelevant occupational laws to put this bias on a particular group of people."

While Stigers and her attorneys wait on a judge to set a date for the oral arguments Missouri is working to pass a bill that would make the lawsuit moot by deregulating hair braiding and imposing a simple £20 ($25) fee to register the business.

Governor Eric Greitens, a Republican, specifically called out Stigers' case as "burdensome" in his January state-of-the-state address.

"We need to end frivolous regulations like these so that our people can start their own businesses and create jobs," he said.

Stigers may have found a political ally in new Missouri governor Eric Greitens

The conservative political powerhouse run by Charles and David Koch has also taken a stand against the licensing regulations as part of a £737,280,000 ($900m) campaign for a free market that encourages small business growth.

Former President Barack Obama issued a call to action to cut down on the state licensing regulations that require nearly one in four American workers to obtain an occupational licence - a huge increase from the 5% who had to get licences in 1950. His administration also allocated federal funds for states who reformed licensing regulations.

Stigers works a lot. She has to carve out time to testify in court and in front of the Missouri state legislators. She just expanded her salon to a new storefront that fits ten braiding booths and a full spa with manicure stations and a soon-to-come sauna.

When she's not braiding a client's hair, she's running to the bank, buying supplies, or discussing business with the eleven other women her business employs.

"It's a constant attack against our hair, our beauty standards, all under the guise of occupational licensing," says braider Pamela Farrell

Stigers said she hopes her lawsuit will help other women realise their dreams of opening a hair-braiding salon.

"I am excited because it's something that, the other native African hair braiders, they see me moving and expanding and they don't have to be afraid of being out in the public eye," Stigers said.