California's drought is over. Now what?

- Published

Wildflowers bloom in Death Valley after heavy rains

Now that California has had significant rain, can the state ever go back to "normal"?

At the height of California's multi-year drought, Rafael Surmay's well - the only source of water to his house - went dry. For two and a half years, Surmay, his wife, and his four children showered, cleaned, drank and cooked using a water tank and 10 gallons of bottled water per month. They depended on monthly deliveries to refill their water tank

"To manage the water was practically the main track of each day," he says."We disconnected the washer and had to go to the public laundry. For showering, every time I tell my boys, soap, close the shower [faucet], wash, close."

Over the past several months, rainstorms have brought relief to parts of California, which has been suffering from drought since 2012. Some areas have had record rain, and snowpack across the Sierra Nevada is between 150-175% of normal.

Though a small percentage of California is still in moderate to severe drought, external, California Governor Jerry Brown may declare an official end to the drought emergency in the near future.

But several years of widespread, deeply dry conditions have exacted a toll on the state that will take more than one wet season to fix. In some cases, the landscape may be forever altered.

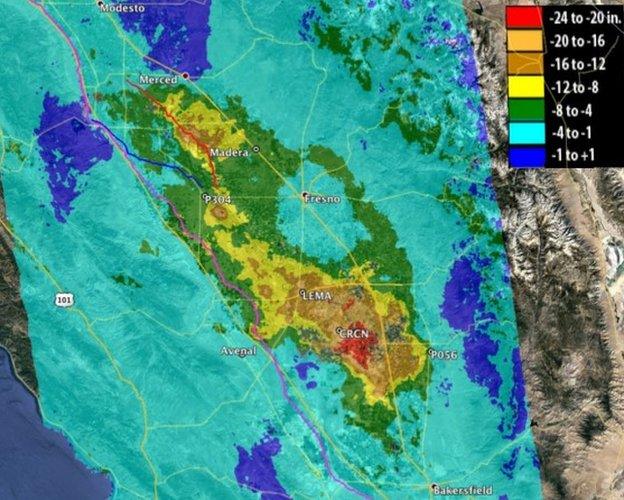

In parts of San Joaquin Valley, where the Surmays live, the ground is sinking as fast as two feet a year, because of over-pumping of groundwater, according to a new study by Nasa's Jet Propulsion Lab, external.

Rafael grabs drinking water from a neighbour in 2015

As the drought continued, people dug deeper and deeper to extract water from the ground, and that's taken a toll. Groundwater aquifers in this area have layers of clay whose particles are like "little plates," says Kathleen Jones, one of the paper's authors.

"They take up a lot of room, but whenever you over draw, they flatten, and they don't fluff back up."

And as the ground sinks behind the water being pumped out, the aquifers don't hold as much water afterwards.

Alan Haynes, a hydrologist with the National Weather Service says some of the shallower groundwater reserves will respond to the rainy season, but others may take much longer. Claudia Faunt, a US Geological Survey researcher, says even if all groundwater pumping stopped, it would take decades for aquifers in the Central Valley to fully recharge.

These deeper basins collected water over thousands of years, Hayes said. "It's almost like fossilised water."

Ground subsidence in San Joaquin Valley

And that means despite flooding in some parts of the state, the drought's effects still reverberate.

David Lewis, another resident of the San Joaquin Valley whose well has gone dry, is moving instead of digging a deeper well. The lack of water has extended to his work at the cement plant - where its own well ran dry in early March.

Last month, after years of planning and advocacy efforts from local non-profits, the Surmays' house and many of their neighbours were connected to the city of Porterville's water system.

But the infrastructure that now brings water to their house itself is at threat due to the subsidence. Ground shifts can affect roads, bridges, water pipes and aqueducts.

The Nasa study focused on land around California's vast water infrastructure, which brings water from the northern part of the state to the southern - across hundreds of miles.

"There is a huge mismatch between where and when the water falls and where and when people use it," Jones says. One of the results of the JPL study: as result of the sinking ground in one area of the aqueduct, water flow is hampered by 20%.

The governor has signed a new law requiring localities to manage groundwater more sustainably, but it does not go into effect immediately.

The California aqueduct moves fresh water across the state from Northern California into the irrigation networks of the central valley and into the southern California

"Subsidence has long plagued certain regions of California," William Croyle, a state water official, said in a press release. "But the current rates jeopardise infrastructure serving millions of people. Groundwater pumping now puts at risk the very system that brings water to the San Joaquin Valley. The situation is untenable."

That flow downstate affects farming in California too. During the drought, farmers either let their fields fallow or began digging for groundwater themselves. While California farmers as a whole saw higher revenue at the height of the drought, success was uneven and driven by higher prices.

In 2015 alone, there were 2,500 new wells drilled by farmers in San Joaquin Valley., external.

But in some cases, it wasn't enough. "I don't know a farmer that hasn't reduced [water consumption] by 25%," says Paul Wegner, president of the California Farm Bureau. Some didn't farm at all.

In southern California, thousands of acres of citrus were removed because of drought, external. Other farmers have shifted to less water-intensive crops like wine grapes or berries, or higher-value crops like walnuts and almonds.

California may be in a better position now, but it remains at risk of another intense drought.

"In the past five years we weren't seeing these mid-winter storms," says Alan Haynes, a hydrologist with the National Weather Service.

Much of the rain depends on luck and how the weather breaks.

"You can lock into ridge of high pressure and it steers everything away, or there's a pattern where the storms can get in."

Climate change has a part to play, but less so with the amount of precipitation and more an increase in average temperatures earlier in the year, says Paul Ullrich, a climate scientist and professor at University of California, Davis.

"That means over the summers, more water is evaporating from the ground," Ullrich says. Rising temperatures also limit the amount of snowpack in the high mountains over the winter, and melts it even earlier.

"No matter how much it snows during the rainy season, rising temperatures will continue to remove water from the state," says Ullrich.

That means any gains now are tenuous.

"If we have another dry season - you can easily get back into trouble again," Hayes says.

After five years of living under the harsh realities of drought, he says, a lot of state residents won't change their water-conserving habits.

"That memory is going to be around for a while."