Seeking funds to say a final farewell to sons on death row

- Published

Marilyn Shankle-Grant on a recent visit with her son, Paul Storey

For the families of men facing the death penalty, money can be a barrier to seeing a loved one before the end.

Marilyn Shankle-Grant's son, Paul Storey, has been fighting his death sentence for almost 10 years. All his legal efforts so far have fallen short, and in autumn, a judge set his execution date for 12 April, 2017.

Storey was convicted in the 2006 shooting death of 28-year-old Jonas Cherry during an armed robbery. Storey's accomplice - the gunman - pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life in prison. Storey went forward with a jury trial and received the death penalty in 2008.

Since he was sent to death row, Shankle-Grant has been able to see her son about once a month, making the four-hour drive from her home in Fort Worth, Texas, to the state prison in Livingston, Texas.

But recently things have got more difficult for the 57-year-old hospitality worker. The stress and depression over her son's impending execution was affecting her work performance, and she lost a job she had held for 30 years.

She tried to pick up temporary work, and even started her own business, Marilyn's Old-Fashioned Tea Cakes, baking flat, buttery rounds from her grandmother's recipe, wrapping them up in cellophane and selling them at local events.

But even that small income stream has dried up - she stopped making tea cakes not long after her son's execution date was announced.

"When I do them, I do it with lots of love," she explains. "Right now that's just not in me."

The situation has become dire - her Forth Worth home entered foreclosure this week. She needs $8,000 (about £6,400) to save it.

The prison in Livingston, Texas, where Paul Storey and other death row inmates are held

Her financial difficulty - not to mention her broken car - have made the trips to Livingston a real financial strain, at the same time that the approaching execution date makes them more important than ever. She estimates each trip costs roughly $350.

With just six weeks left to visit before her son is executed, Shankle-Grant posted a weary status to her Facebook page, lamenting the short amount of time she has left with her son and the financial struggle she faces just to see him.

It caught the eye of Abraham J Bonowitz, co-director of Death Penalty Action, an anti-death penalty charity. He had met Shankle-Grant many times over the years at death penalty abolition events.

Bonowitz reached out to Shankle-Grant to ask her permission to set up an online fundraiser on her behalf. He created a page on the crowdfunding site You Caring, which included a note from Shankle-Grant.

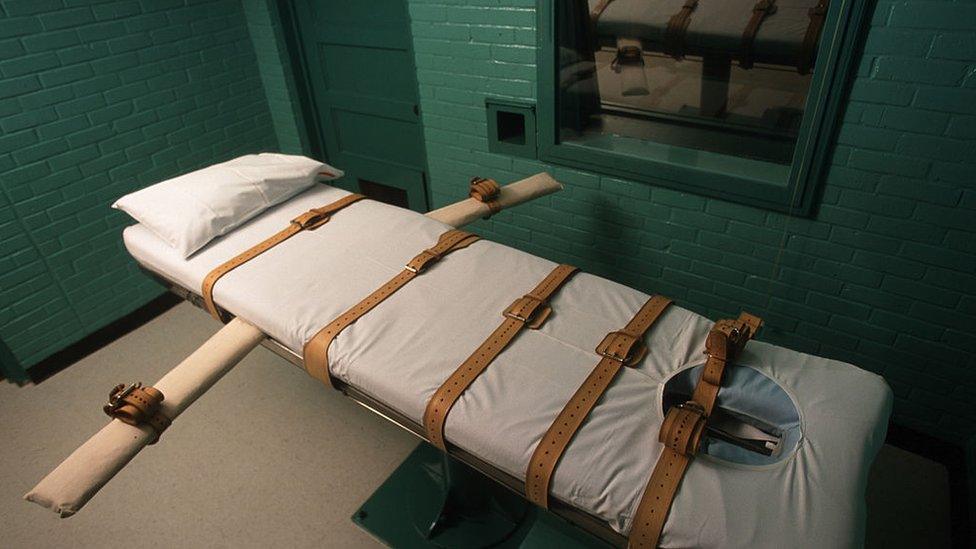

The death chamber in Huntsville, Texas

"My love and devotion to my son are not matched by the resources needed to make the trip as often as I am allowed to visit him," she wrote. "With a heavy heart I turn to my fellow human light to ask you to help me help my son face the darkness as his destruction approaches."

The donations began streaming in. One anonymous donor contributed $1,000.

"My father was executed in Texas 13 years ago, and while the situation is still painful, I'm thankful for our last few visits, and I know he was as well," wrote one contributor.

"Nobody's going to be able to take away the pain that Marilyn has, but we can take away some of the anxiety," says Bonowitz, who is considering making these fundraisers a permanent part of his work.

So far, he has raised nearly $6,000. The money allows Shankle-Grant to rent a car each weekend, stay for two nights in a nearby hotel, as well as pay for meals and gas.

Thanks to the funds, Shankle-Grant has been able to visit her son every weekend since. She says she is incredibly grateful for the help.

"None of this would be able to be happening if it weren't for that You Caring page," she says. "I'm able to talk to him. When he's down and out and depressed, we can talk about it and talk him through it. It gives me comfort, too."

Abraham Bonowitz at an anti-death penalty rally he hosts in front of the US Supreme Court each year

Shankle-Grant's situation illustrates the hidden impact on the families of the condemned, who often come from low-income backgrounds and can live far away from the prison in which their loved one is housed. After 30 years of death penalty abolition work, Bonowitz has seen the situation many times before. Often a church or a non-profit will step in to help defray the cost of visiting a family member before an execution.

"None of these families have any money," he says. "Marilyn never did anything wrong and yet she is made to suffer. It's her son's fault, yes, but that doesn't mean the love for her child stops."

The success of the fundraiser caught the attention of advocates in Arkansas, which is poised to execute eight inmates over the course of 10 days, due to the fact that the state's supply of an execution drug called midazolam is about to expire.

Deborah Robinson, a freelance journalist who is writing a book about the eight men, says she has heard from three of them, asking for help so that their families can see them before the execution dates in late April.

"I have a 21-year-old daughter whom I haven't seen in 17 years, along with a 3-year-old granddaughter," wrote inmate Kenneth Williams, who is scheduled to die on 27 April, in a message to Robinson.

"The financial costs have prevented her from coming. If I am going to be executed, I would love to see her before I go one last time and to see my grandchild for the first time."

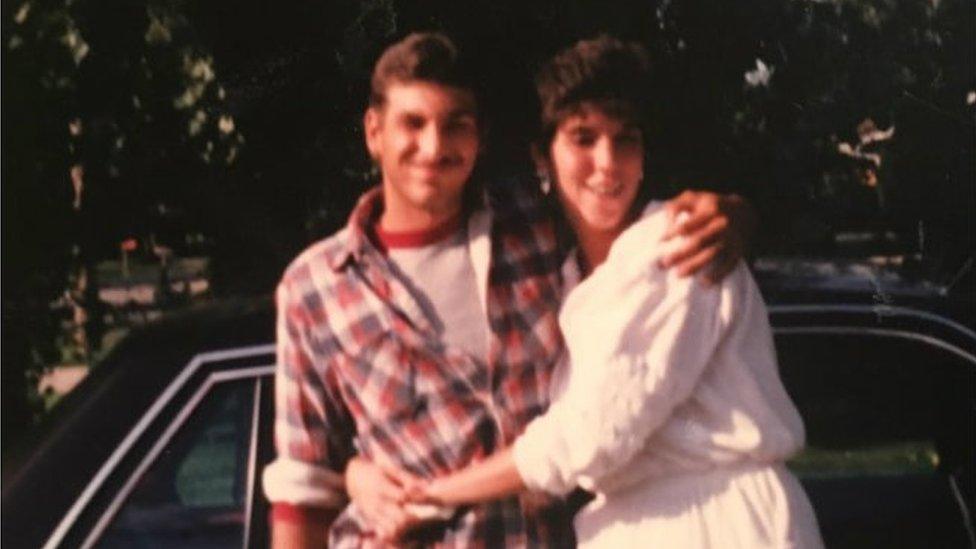

Lynn Scott with her brother Jack Jones, Jr, who has been in prison since 1995

Lynn Scott, the sister of death row inmate Jack Jones, Jr, lives in North Carolina. She runs her own business as a wedding planner, but she and her husband lost nearly everything after the 2008 recession - their house, their 401k, they sold off most of their possessions. After Scott's husband suffered a massive heart attack in 2015, they found themselves financially devastated.

"We live paycheck to paycheck," she says.

Arkansas is scheduled to execute her brother on 24 April. With airfare, hotel, car rental and meals - plus cremation and burial expenses - she expects that she will need about $5,000.

"It's very difficult," says Scott. "What I want people to know is - whatever the inmates did, we didn't do that. I didn't do that to those people, but I'm still losing someone."

Modelling a crowdfunding page after the one in Texas, Robinson is now raising funds for all three Arkansas families, external to help defray some of those costs.

Shankle-Grant and Storey on a visit in 2014

If Shankle-Grant's You Caring page raises more money than she can use to see her son, she says she wants the excess funds to go to the families in Arkansas.

Her son, Storey, still has a lawyer fighting for a stay of execution, in part based on the fact that his victim's parents are opposed to the death penalty, external and do not want him to be executed. Glenn and Judy Cherry have written letters to Texas Governor Greg Abbott and other state officials asking for mercy.

Shankle-Grant still holds out hope that her son's execution will be halted, and the portion of the fundraiser money that is designated for her son's burial can be sent to the other families. She is asking supporters to write letters, external to the Texas Department of Corrections, asking that Storey's life be spared.

In the meantime, because of a court hearing Storey has been moved to a county jail that allows him to use the phone for the first time in years (phone calls are not allowed for death row inmates in his prison). Shankle-Grant says he has been able to talk to his elderly grandparents, who can't travel to see him, and thanks to the fundraiser, she was easily able to pay the hefty $300 phone bill. She is also able to talk to him, sometimes as often as four times a day.

It's a small comfort as the execution date creeps closer and closer.

"He'll hang up and call back, hang up and call back," she says. "I don't know after [nine] days if I'm ever going to hear his voice again. For me, it's very important."

If an inmate's family does not make other arrangements - which can cost thousands - they are buried in this prison cemetery in Huntsville, Texas