The inflammatory telegram that pushed the US into World War One

- Published

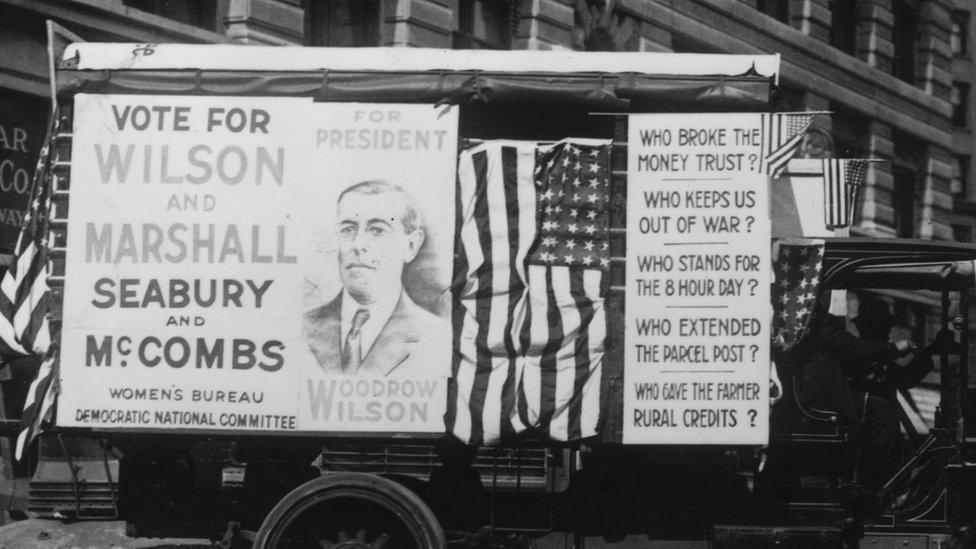

Woodrow Wilson

When Congress finally gave its approval to go to war in April 1917 it was a decision most observers at the time regarded as unavoidable. Author Patrick Gregory explains how the US got to that point.

The slide towards war had begun just over two months before, the result of a decision by the Imperial German Government to resume its policy of unrestricted U-boat warfare - the targeting of any and all shipping, including American vessels - in the coastal waters around the British Isles.

Yet war, if now unavoidable, had not always been inevitable. Far from it.

US President Woodrow Wilson had strained every political sinew in the previous two and a half years to keep his country out of the conflict, often in the face of intense political opposition.

Wilson was a reserved, almost severe intellectual of Scots Presbyterian descent. Troubled by what he saw of war - the US Civil War - in his own native southern states as a child, he resolved to keep his and his country's nose out of the conflict when Europe began to erupt in 1914.

It was a conflict whose causes and objects he viewed as at best obscure. American foreign policy would not be advanced, he felt, by participation.

Neutrality was to be Wilson's watchword and word of the nation's dealings in Europe: to be neutral "in thought as well as in action", to the chagrin of many critics, including prominent Republicans like former President Theodore Roosevelt.

Yet Wilson held to his policy in the years following, even in the face of some extreme provocation. The most prominent example of the latter came in May 1915 with the sinking of the passenger liner RMS Lusitania, torpedoed by a German U-boat off the southern Irish coast. Nearly 1200 people perished, including 128 Americans.

Whilst the chorus of protests grew, demanding redress and intervention, Wilson eventually obtained a partial retreat from the German government. In September 1915, Kaiser Wilhelm II issued an order to the effect that Germany would henceforth refrain from sinking passenger ships without warning.

A depiction of the sinking of the RMS Lusitania

So an uneasy calm endured. Wilson headed off some critics with 1916's National Defence Act, aimed at boosting the size of the army - an answer to those in the Preparedness Movement who felt that if war were to suddenly arrive, America would be found wanting. But still, his brand of watchful caution held sway. He even campaigned in the run up to that year's Presidential elections under the banner "He Kept Us out of War".

He won, albeit with the slimmest of margins. By January 1917 he was even daring to look to the future, addressing the Senate in a speech where he asked them to help in his quest to forge the "foundations of peace among the nations" once conflict was at an end.

So when the turn in events came, changing that outlook, it came suddenly and abruptly. Barely over a week after his speech to the Senate, on 31 January, the German ambassador to Washington called on Wilson's Secretary of State Robert Lansing.

US Troops on the move during World War 1

He had with him a letter declaring that Germany was to resume its policy of unrestricted U-boat warfare. The clock was now ticking. First diplomatic ties were severed, then a halfway-house of what Wilson termed "armed neutrality" was tried, but events had their own momentum.

Public opinion was inflamed by the emergence of a telegram, purportedly from the German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman, offering military assistance to Mexico if the United States entered the war on the Allies' side.

The proposal from Zimmerman, through the German embassy in Mexico, was a straightforward one, written in a most to-the-point fashion: "Make war together, make peace together"

If it did, Mexico could expect generous financial support to reconquer lost territory in the United States: in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. "The ruthless employment of our submarines," said Zimmerman, would lead to peace in just a few months.

Some detected a cynical motive from those on the Allied side who wanted to see America in the war. But on 29 March, the minister addressed the matter in a speech admitting his involvement, even pressing home and justifying his argument with reference to the "hostile attitude" of the American government.

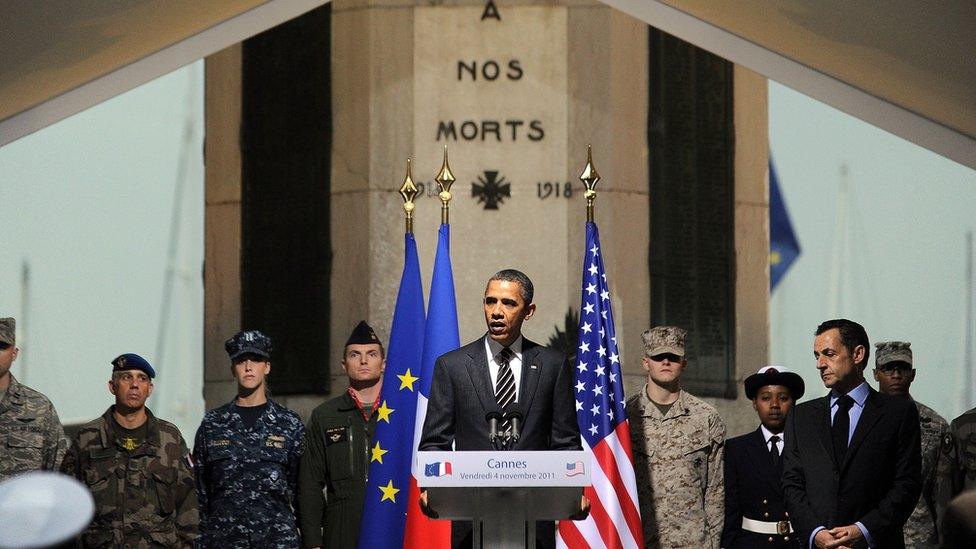

US President Barack Obama (L) talks next to his French counterpart Nicolas Sarkozy during a ceremony at a World War I memorial

On 2 April Wilson found himself before a joint session of Congress. With a profound sense of the solemn and tragic step he was taking, he said, Congress should declare German actions to be nothing less than war against the government and people of the United States.

Armed neutrality had been ineffectual. It had proved impracticable in defending shipping against attack from "outlaw" German submarines. "We have no quarrel with the German people. We have no feeling towards them but one of sympathy and friendship," he said. But, "the world must be made safe for democracy".

Two days later the Senate voted in favour of Wilson's resolution, and two after that it was endorsed by the House of Representatives. Later that same day, 6 April 1917, the President signed his official declaration. America was at war.

Patrick Gregory is the co-author with Elizabeth Nurser of An American on the Western Front: The First World War Letters of Arthur Clifford Kimber 1917-18 , external(The History Press, 2016). He tweets at @AmericanOnTheWF, external