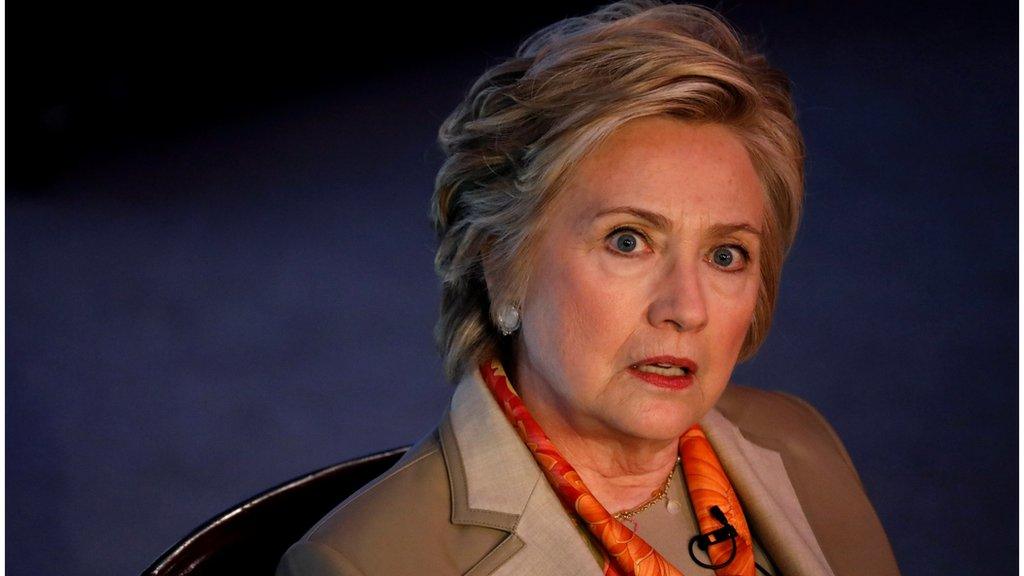

Hillary Clinton joins the 'Trump resistance'

- Published

The election may be over, with Donald Trump's presidency more than 100 days old, but Hillary Clinton isn't ready to let go.

In a brief but frank interview with foreign affairs reporter Christiane Amanpour at the Women for Women International event in New York City on Tuesday, Mrs Clinton said that she has conducted an "excruciating analysis" of her failed presidential campaign as part of a book she is writing.

What has she learned? While admitting that she made mistakes and that her campaign had "challenges", "problems" and "shortfalls", she pointed the finger at two men - FBI Director James Comey and Russian President Vladimir Putin - as the proximate cause of her defeat.

"I was on the way to winning until the combination of Jim Comey's letter on October 28 and Russian Wikileaks raised doubts in the minds of people who were inclined to vote for me but got scared off," she said. "The evidence for that intervening event is, I think, compelling."

Mrs Clinton also noted that as the first woman to run for president as a major party candidate, misogyny may have also been a factor in her loss.

"It is real," Mrs Clinton said of discrimination against women. "It is very much a part of the landscape politically, socially and economically."

She said her election would have been "a really big deal" for women's rights, sending a message around the world.

At one point, Amanpour joked that the president would likely take to social media to respond to the former candidate's remarks .

"If he wants to tweet about me then I am happy to be the diversion because we have lot of things to worry about," Mrs Clinton said.

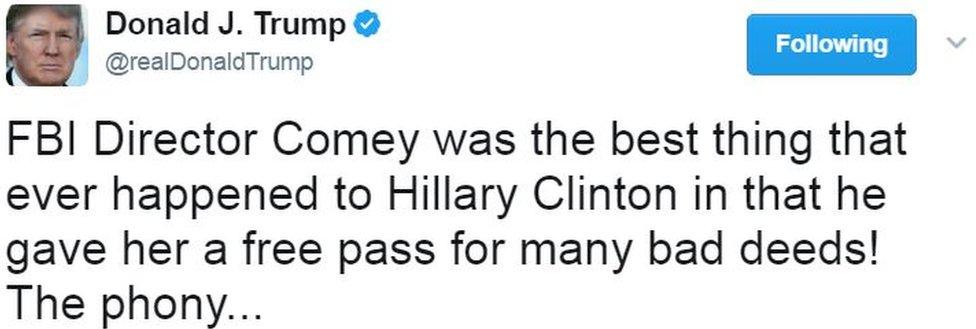

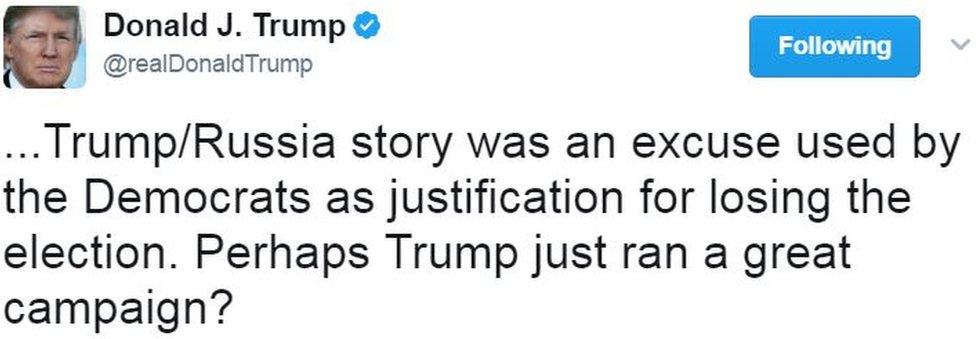

By that evening, Mr Trump indeed offered his Twitter response, again saying the Russia allegations were a Democratic attempt to avoid blame for their defeat.

Other opponents of the former secretary of state will be quick to point out that explaining away her campaign missteps as mere challenges, problems and shortfalls gives short shrift to strategic lapses that left her vulnerable to Mr Trump's economic populism, allowing him to prevail in the decisive Rust Belt states of Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Michigan.

Mrs Clinton's apparent response, however, is that she had to defend Mr Obama's presidential accomplishments and sell her pragmatic approach as the way to improve American lives.

"That was not as exciting as saying throw it all out and start over again, but it's how you make change in America - and lasting change that would improve people's lives," she said.

When it came to foreign policy, Mrs Clinton shared some thoughts on the "wicked problems" currently confronting Mr Trump.

She said the effort to end North Korea's nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programmes requires a regional effort, with US positions presented in critical negotiations and "not just thrown off in a tweet some morning".

WATCH: What is Trump's plan in Syria?

She also said she supported the recent US missile strike to punish the Syrian government for its use of chemical weapons, although she says she is not convinced it has made much of a difference.

"If all it was was a one-off effort," she said, "it's not going to have much of a lasting effect."

Instead, Mrs Clinton is left trying to find her footing as an ex-candidate with no electoral prizes on the horizon for the first time since she emerged from her husband's political shadow. As her numerous swipes at the current president reveal, however, she may find an identity in opposition.

"I'm now back to being an activist citizen and part of the resistance," she said toward the end of her interview, referencing the label many of Mr Trump's liberal opponents have adopted.

The grassroots movement aiming to topple President Trump

Playing backseat driver to the Trump presidency isn't where Mrs Clinton wanted to be, of course. It's not where, 10 days before last November's election, she thought she'd be. And dealing with it, she said, has been a "painful process".

If Mrs Clinton's psychological wounds never truly heal, she will hardly be the first to endure such lasting damage, as an anecdote recounted by political reporter Roger Simon reveals.

Shortly after his presidential defeat in 1984, Democratic nominee Walter Mondale called George McGovern, who was beaten by Republican Richard Nixon in 1972.

When does the pain stop, he asked. When did you wake up in the morning and not feel like throwing up?

"I'll tell you when I get there," McGovern replied.