Comey sacking doesn't rise to Watergate levels

- Published

The New York Times called for the president to leave office immediately, describing it as "the last great service" he could perform for the country.

The Washington Post demanded impeachment, followed by a Senate trial. Time magazine, deeming it necessary to publish its first-ever editorial, thundered: "The president should resign."

Outside the White House, protesters waved placards at passing motorists: "Honk for Impeachment." Even Washington's most influential columnist, Stewart Alsop, who was normally supportive of the president, called him an "ass." The president had lost his moral authority, argued his critics, and with it, his ability to govern. The country faced a constitutional crisis. The republic was imperilled.

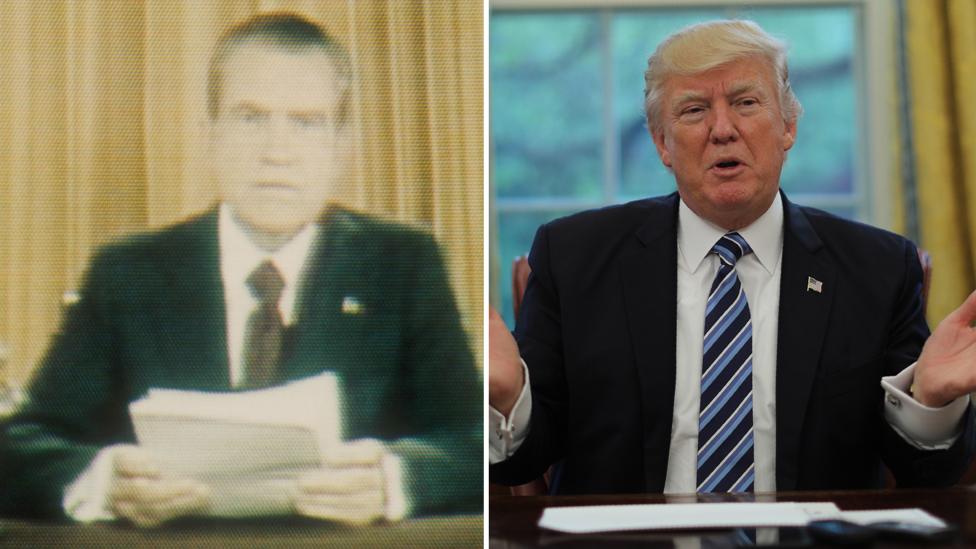

Such was the feverish reaction to the events of 20 October, 1973, a date remembered in the national memory as the "Saturday Night Massacre" - a pivotal moment in the unfolding Watergate controversy.

With scandal engulfing the White House, Richard Nixon decided to fire Archibald Cox, the special prosecutor appointed to investigate "all offenses arising out of the 1972 election… involving the president, the White House staff or presidential appointments".

John Dean spoke to BBC radio about Watergate

Nixon's Attorney General, Elliot Richardson, and his Deputy Attorney General, William Ruckelshaus, resigned rather than carry out the president's order. Eventually, the Solicitor General Robert Bork, who was third in command at the justice department, was prepared to fire Cox.

The White House announced the news at 20:22 that Saturday evening.

On Wednesday, almost as quickly as the news that he had been sacked as head of the FBI reached James Comey in Los Angeles, these two dramatic episodes were being described as historically analogous.

The president had fired the lead figure in an investigation into alleged wrongdoing by members of his own team.

The Nixonian parallels were obvious.

Roger Stone, a Trump associate who also worked in 1972 for the notorious Committee to Re-elect the President, told the New York Times: "Somewhere Dick Nixon is smiling."

The Nixon presidential library even trolled the White House on Twitter: "FUN FACT: President Nixon never fired the Director of the FBI #FBIDirector #notNixonian."

Democrats insinuated that Comey was fired for similar reasons to Cox, because he was closing in on the truth.

There were other resemblances, too. In the lead-up to the Saturday Night Massacre, the Nixon White House was still reeling from the resignation of the president's chief of staff, Bob Haldeman, a central figure in the Watergate scandal, just as the Trump administration continues to be buffeted by the swirl of controversy surrounding the forced departure of Gen Michael Flynn, his former National Security Adviser.

There's the suspicion now, as there was four decades ago, that an embattled White House has something to hide.

So is this truly a re-run of the events of 1973? Is the past repeating itself?

Even by the standards of the Nixon presidency, the autumn of 1973 was unusually chaotic.

Flynn before his departure from the White House

It saw the resignation of Vice-President Spiro Agnew because of fraud, tax evasion, bribery and extortion allegations.

The Middle East was in the grip of the Yom Kippur war, a conflict between US-backed Israel and Arab forces armed by the Soviets that threatened to blow-up into a broader conflagration between Washington and Moscow.

In Washington, Nixon was fighting a pitched battle with Archibald Cox and the courts.

Cox, a Harvard professor who had been appointed as special prosecutor in May that year, had issued a subpoena ordering the White House to hand over nine tapes of phone calls and West Wing conversations in connection with the Watergate break-in. Nixon's legal team argued the principle of executive privilege should apply, and the tapes should remain private.

On 12 October, however, the Court of Appeals in Washington upheld a lower court's ruling granting Cox's request. Rather than comply, Nixon decided to fire the special prosecutor, something his Attorney General Elliot Richardson had promised Congress would never happen.

A president stood in defiance of the courts, putting himself above the law of the land. It was a textbook constitutional crisis.

Donald Trump's sacking of his FBI director, while highly unusual and deeply controversial, is constitutionally permissible. No court orders have been flouted. The president, while breaking with the norm of allowing FBI directors to serve out their 10-year terms unimpeded, is not putting himself above the law.

Trump's motivations may also be different. Nixon sacked Cox through fear his criminality was about to exposed.

Within the FBI, agents believe that Trump sacked Comey primarily out of pique and spite because of his refusal to publicly exonerate Trump against allegations of collusion with the Kremlin, and also because Comey refused to back up Trump's unsubstantiated claims that Barack Obama ordered the wire-tapping of Trump Tower.

Trump's love-hate relationship with Comey over a tumultuous year

Unlike the Saturday Night Massacre, the president is at one with the most high-ranking figures in the justice department rather than at odds with them. The president, the attorney general and the deputy attorney general together they made the case that Comey should go - not purportedly because of his investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election, but because of the former director's handling of the Hillary Clinton email investigation.

The politics is also very different. Back in 1973, the Democrats controlled both the Senate and House of Representatives. That put the investigative machinery of Congress in their hands. Senate hearings were already under way, and the Saturday Night Massacre gave them fresh impetus.

Nixon also faced an acid shower of criticism from Republicans on Capitol Hill and around the country. "Clearly we face a constitutional crisis," lamented the Republican governor of Michigan.

Literally Nixonian: Trump and Nixon Secretary of State Henry Kissinger talking in the Oval Office the day after Comey's firing

There have been Republican critics of Trump's decision to fire Comey. But so far they haven't been so vehement. Crucially, the Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell is resisting demands from the Democrats, and some in his own party, to back calls for the appointment of a special counsel to investigate the 2016 election.

Politically, Donald Trump remains strong, because of the support of the Republican leadership on Capitol Hill and his grassroots supporters in the American heartland.

Nixon, by contrast, was politically weak. This became apparent only a few days later when the White House indicated it would hand over the tapes, which included a recording of the infamous conversation between the president and Haldeman, eighteen and half minutes of which were missing.

Nixon was also forced to appoint a new special prosecutor. And eventually, of course, the push for impeachment gathered unstoppable momentum, and he was forced to resign as president.

In 1973, Democrats were hollering impeachment. In 2017, the party's congressional leadership has not publicly uttered that explosive word.

What may be similar between now and then is the intemperate mood of the president. As demonstrated by his Twitter tirades, Donald Trump is lashing out publicly against his critics, much as Nixon did privately in his final months in office.

Senator Marco Rubio being interviewed by reporters about Comey firing

Politico is reporting that Trump shouted at the television over the Russian investigation, which again has echoes of Nixon's executive mansion tantrums.

Curiously, both presidents also saw Florida as a bolt-hole from the pressures of Washington, Nixon opting for Key Biscayne, Trump regularly visiting Mar-a-Lago - although a key difference is that Nixon medicated himself with alcohol, while Trump is famously teetotal.

But the Saturday Night Massacre and the Tuesday Night 'You're fired" are not directly comparable.

The sacking of Archibald Cox contributed heavily to Nixon's forced departure from the White House. It was widely seen as an impeachable offence.

The removal of James Comey, in and of itself, does not pose such an existential threat to the Trump administration.