Arctic summit: Alaskan fears amid the vanishing ice

- Published

The BBC's James Cook explains why the Arctic Circle summit in Alaska matters

It's springtime in Alaska and a gentle drip-drip and occasional creak and crack tells you that the winter ice on the shore of the Bering Sea is melting fast.

In the little town of Nome ("there's no place like Nome," as they say here) folk reckon that these thaws are coming earlier, summers are longer and the ice is thinner.

To them climate change is not just a theory.

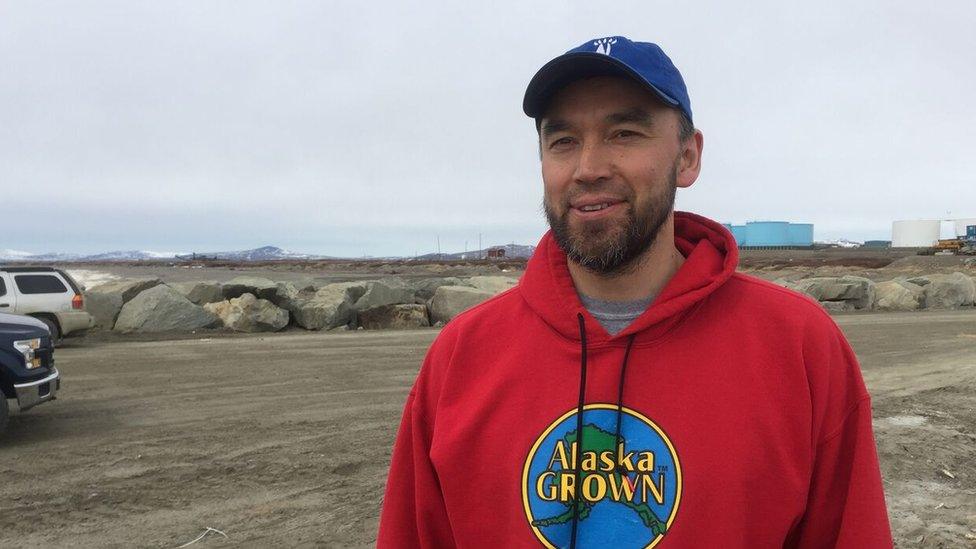

"When I was younger this shore-fast ice was upwards of eight feet," says Austin Ahmasuk who has been gazing out at this icy water since the day he was born. "Now its wintertime maximum is four feet thick or so."

Fierce winters can cut Nome off, as in 2012 when icebreakers were needed to deliver fuel

Austin Ahmasuk says the area faces 'mind-blowing' oceanic changes

Mr Ahmasuk works with Kawerak, external, a consortium of 20 local tribes including Inupiaq, St Lawrence Island Yupik and Central Yup'ik peoples - trying to maintain old traditions in a new world.

"In Alaska," he says, "we are witnessing the disappearance of the cryosphere, external - ice - in many parts where it occurred in all of its forms: permafrost, river ice, ocean ice."

The resulting oceanic changes are, he says, "mind-blowing".

Trump scraps Obama's climate change policies

Trump's 'control-alt-delete' on climate change policy

This changing face of land and sea hampers the mobility of isolated communities, making hunting harder and challenging ways of life which have endured for thousands of years.

'Longer summers'

Along the beach, Rebecca Tokeinna and her mother Peggy Olanna are not hunting, but scavenging for flat stones to decorate their new home.

It is a few degrees above freezing today and the sun is out so both mother and daughter are wearing shorts. "It's summer," they declare, with broad smiles.

They have recently moved south from the Arctic village of Wales from where, on a clear day and in the right spot, you can see Russia across the strait, external.

They too are reporting changes.

"The winters are colder and a little bit shorter and spring is coming earlier and a lot warmer, which we love. Summers are longer instead of shorter," says Ms Olanna.

The winter which has just ended was particularly fierce, she says, although she adds that it followed several milder winters.

"The elders, they are watching the climate change," says Ms Olanna.

"Back in the day they knew exactly when to go out hunting. Now they have to play with the weather."

Rebecca Tokeinna and Peggy Olanna say they are noticing the winters are shorter

There is no doubt that people here are tough and resilient.

Through the long, dark winters when ferocious storms scream in from the sea, survival is not guaranteed and there is no-one to turn to for help.

And yet now, with conditions changing so rapidly, there is a feeling that help may be needed, that local problems are becoming global concerns.

'Abdication of responsibility'

Halfway across Alaska, climate change is the biggest issue at the biennial meeting of the Arctic Council in Fairbanks which brings together the foreign ministers of the eight nations with territory in the Arctic along with representatives of indigenous communities.

Mr Trump promised to support the coal industry during his campaign

Many delegates here say they are confused about the position of the United States which, under the administration of the previous president, Barack Obama, a Democrat, made tackling climate change a priority.

Most significantly Mr Obama approved the 2015 Paris climate change accord to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, which was negotiated by around 200 nations.

His successor in the White House has taken an altogether different approach.

Before becoming president Donald Trump tweeted that climate change was a Chinese hoax, external.

He has appointed a former chief executive of the oil major Exxon Mobil as secretary of state.

The Environmental Protection Agency is now being run by a fierce critic of Obama-era climate policies and the White House has caused consternation with executive orders which could lead to the production of more coal and more oil and gas exploration, external.

The biggest question remaining is whether President Trump will go even further and withdraw the US from the Paris accord.

Doing so would set back US climate policy "by a decade or two", in the judgment of Prof John Walsh, chief scientist for the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska, amounting, he says, to "an abdication of responsibility".

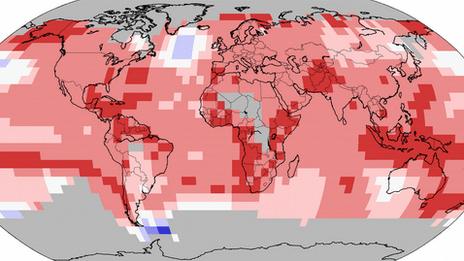

"The warming we've seen in the last 50 to 100 years is greater than the warming we've seen at any time in the last 2,000 years," says Prof Walsh, adding that "human activity is a primary driver of the changes we're seeing".

Climate campaigners fear US policy will damage attempts to combat climate change

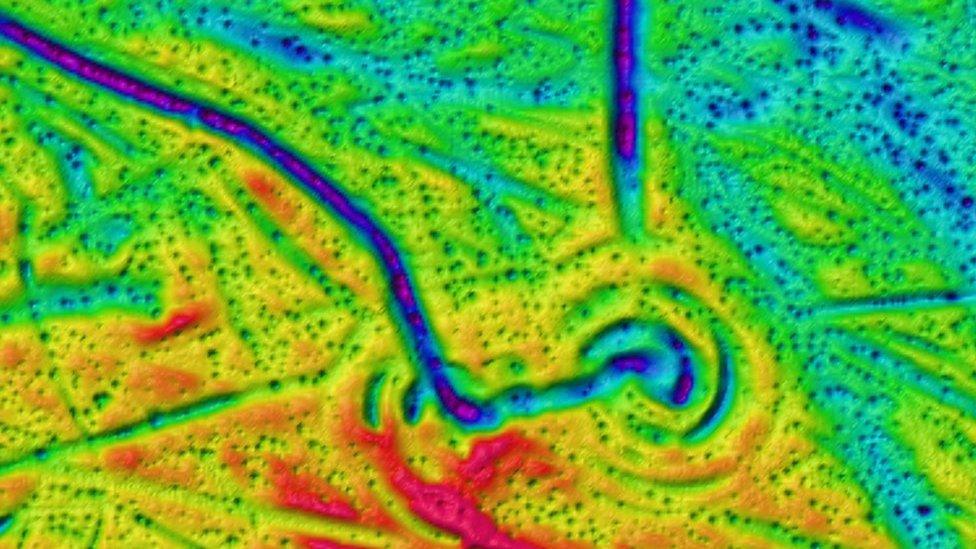

Scientists like Prof Walsh say the effects of a warming climate are being felt particularly keenly here in the Arctic - with sea ice and glaciers melting, permafrost thawing and coastal communities at threat from erosion.

Not only that but the process appears to be accelerating thanks to a so-called feedback loop - the more ice melts, the darker the surface of the planet becomes, with both land and sea reflecting less sunlight and absorbing more heat, and the warmer the world becomes.

The climate is not the only topic on the table at the Arctic Council. It also deals with issues such as fisheries, tourism and shipping.

Finland, which is taking over the presidency from the US for the next two years says its twin priorities, external will be addressing climate change and ensuring sustainable development.

Helsinki will also have to contend with the prospect of increasing tensions in the High North where retreating ice is raising the prospect of a scramble for resources.

Analysts say Russia now has its strongest military presence in the region, external since the end of the Cold War.

"A lot depends on the so-called global drivers, the prices of commodities: oil, gas, minerals," says Prof Walsh, who predicts that "sooner or later, when the commodity prices do trend back upwards, the Arctic is going to be more ripe for exploitation."

There are plenty of people in Alaska who have voiced support for such development, external, but back on the beach in Nome, Peggy Olanna is worried.

"I would say no, that would affect our food from the ocean and we depend on that," she says.

- Published25 April 2017

- Published18 April 2017

- Published29 March 2017

- Published15 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published25 January 2017

- Published21 December 2016