Could Trump be guilty of obstruction of justice?

- Published

Trump seemed to suggest in an interview that the Russia probe motivated him to fire James Comey

Reports that Donald Trump asked former FBI director James Comey to shut down a federal investigation into former national security adviser Michael Flynn have added weight to a possible obstruction of justice case against the president, law professors say.

According to a New York Times account of a memo written by Mr Comey, Mr Trump told the FBI director during a private Oval Office meeting in February: "I hope you can see your way clear to letting this go, to letting Flynn go... He is a good guy. I hope you can let this go."

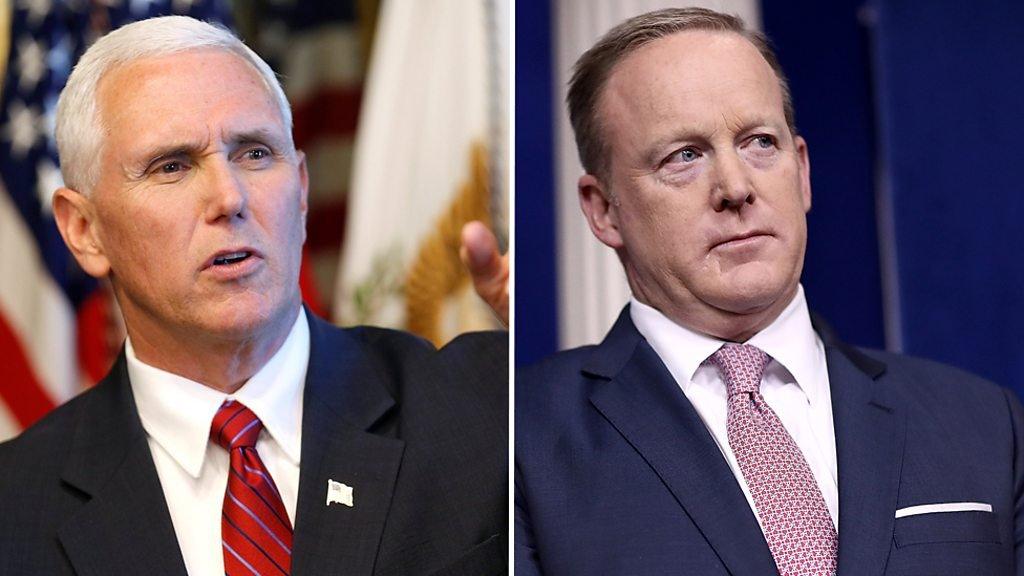

Allegations of obstruction of justice were first levelled in the Comey affair last week, when Mr Trump fired the FBI director and admitted he had taken the "thing with Trump and Russia" into account in his decision. But the case was clouded by a string of contradictory explanations from the White House.

"It was hard to make the obstruction of justice case with the sacking alone," said Alex Whiting, a Harvard Law professor and former federal prosecutor. "The president had clear legal authority and there were arguably proper, or at least other, reasons put forward for firing him. But with this development, that argument becomes much harder to make."

Mr Trump's apparent attempt to lean on Mr Comey to close the investigation was "very close to obstruction of justice", Mr Whiting said, "but still isn't conclusive".

The White House disputed the Times report, claiming it was "not a truthful or accurate portrayal of the conversation".

A question of intent

Under the law, obstruction of justice is any interference with a judicial or congressional proceeding. It is commonly applied in cases where someone has tampered with evidence, intimidated a witness, or failed to report a crime, but the statute requires there to be a corrupt intent behind the action.

There are cases in which an official might legitimately request that prosecutors drop a case, in order for example to avoid the disclosure of classified information. Mr Trump's comments, and the context in which he said them, would have to be assessed for evidence of intent, said David Sklansky, a Stanford law professor.

"This isn't a smoking gun on its own, but I'm not sure you can ever have a smoking gun when it comes to intent," he said. "You prove intent by putting together what someone said with circumstantial evidence and what we know about their actions.

"For example, is it more reasonable to infer, based on what we know about the president, that he was concerned the FBI wasn't prudently shepherding its resources, or is it more reasonable to assume that he was worried about something coming out that would make him or an associate look bad?"

James Comey recorded his meeting with the president in a memo written immediately afterwards

Even if the latter seems apparent, it remains difficult to prove. Circumstantially, the president has several times expressed dissatisfaction with the FBI's Russia investigation. Last week, after the White House said Mr Comey was fired because of his conduct in the Hillary Clinton email affair and not the Russia investigation, Trump appeared to reverse the story, telling NBC News: "And in fact, when I decided to just do it, I said to myself, I said, 'You know, this Russia thing with Trump and Russia is a made-up story'."

Then on Tuesday there was the addition of Mr Comey's memo.

"The memo from Mr Comey seems to be consistent with the president sacking him and saying later that he had Russia in mind when he made the decision," said Michael Gerhardt, a law professor at University of North Carolina who testified at the Clinton impeachment hearings.

"It sounds now as if those events are connected, and that makes the whole situation more disturbing. Was the president using his unique office to suggest to the head of the FBI that he should stop an investigation?"

The Comey memo shifted the legal burden towards the president to explain his actions, Mr Gerhardt said, and put a "heightened burden on Congress to investigate".

A route to impeachment

Obstruction of justice is a criminal offence, but criminal proceedings against the president are highly unlikely, said Mr Sklansky.

"The Department of Justice has concluded in the past that bringing a criminal case against a sitting president would be constitutionally unfeasible," he said. "If there is going to be some kind of legal action against the president it will be an impeachment."

Of the three presidents who have faced impeachment proceedings, two have been accused of obstruction of justice: Richard Nixon in 1974 and Bill Clinton in 2000. Nixon resigned before he could be impeached. The Senate voted on Mr Clinton's impeachment over the Monica Lewinsky scandal but fell 17 votes short of removing him from office.

The sacking of Mr Comey has galvanised President Trump's opponents

The burden of proof for impeachment proceedings is lower than for a criminal case, where corrupt intent must be proved beyond reasonable doubt. The constitution states that for an impeachment, Congress must find that a president has committed "high crimes and misdemeanours".

A successful impeachment requires a majority vote in the House and a two-thirds vote in the Senate, with a trial in-between. With both chambers currently controlled by the Republican party, on purely political grounds an impeachment of Mr Trump, as things stand, seems unlikely.

"The major political question is what it will take to convince large numbers of Republicans that they should no longer support Trump," said Mr Sklansky. "And I don't think we know the answer to that yet."

If the answer takes the form of unwavering support for the president the country could find itself in crisis, said Pamela Karlan, a Stanford Law School professor.

"Right now this is a president behaving extraordinarily badly," she said. "But if it becomes clear that the president is trying to obstruct justice and Congress does nothing, that moves us towards a constitutional crisis.

"If Congress cannot fulfil its role as a check on the president, that's a real problem."

- Published11 May 2017

- Published12 May 2017

- Published12 May 2017

- Published11 May 2017