Conservative Party of Canada: Who will take on Justin Trudeau?

- Published

Selfie hunters will have to hope for a run-in with the real Mr Trudeau in future

As Canada's Conservative Party prepares to vote for its next leader, one question is on everyone's mind: how do you take down Justin Trudeau?

In the summer of 2011, few could predict that today Justin Trudeau would be hailed as a symbol of hope for progressives facing anti-globalization forces. In fact, few could predict that Mr Trudeau would have any role representing Canada on the national stage, period.

Back then, things could not possibly look any rosier for the Conservative Party of Canada, the historical opponents of Mr Trudeau's Liberal Party. Prime Minister Stephen Harper had just won the Conservatives' first majority in more than a decade, and the Liberals were in absolute disarray, having lost both 43 out of 77 seats in parliament, and their status as official opposition.

Without a leader, and almost completely cut off of from voters in the west of the country, the Liberals had little to do but lick their wounds.

In 2006, Harper ended 13 years of Liberal rule. By 2011, his government would have a majority.

Flash forward to today. After winning the Liberal leadership race in 2013, Mr Trudeau led his party to victory in October of 2015, securing a majority government and heralding a new era of "sunny ways" politics.

At the party's leadership convention on 27 May. the Conservative Party will face the task of picking Mr Trudeau's challenger in the 2019 election. With 13 candidates, there are no clear front runners and few big names.

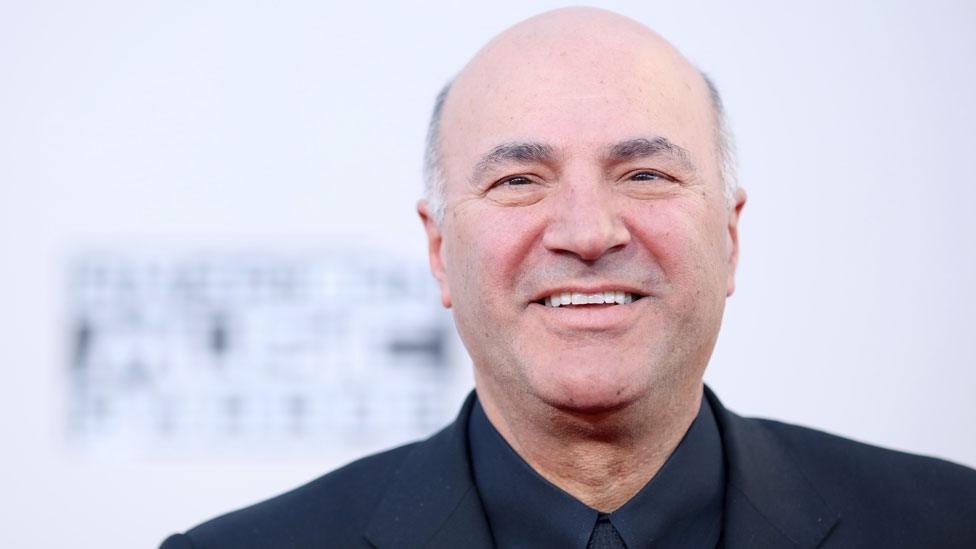

Shark Tank host Kevin O'Leary earned comparisons to US President Donald Trump for his reality TV credentials and outsider status, but ultimately dropped out of the race.

"All the candidates say 'I'm the person who can beat Trudeau'," Peter Woolstencroft, a political scientist at the University of Waterloo, told the BBC. "But it's going to be very hard to beat him."

Only a few of the students seem to have spotted Justin Trudeau mid-jog behind them

With Vogue-ready hair and an affinity for selfies and surprise photo-ops, it will be very hard for anyone to challenge Mr Trudeau in the charisma department. But a candidate with a clear economic strategy that targets voters in specific districts may stand a chance, says Ian Brodie, who was Mr Harper's chief of staff for many years.

"I don't think anybody's going to be able to out-Trudeau Trudeau," he adds.

In order to differentiate themselves in a crowded race, some candidates are trying to position themselves as reformers of the party, Mr Brodie says.

Maxime Bernier has proposed a more radically libertarian economic strategy, while Michael Chong has presented himself as a moderating force who would reign in social conservatives.

Meanwhile, Kellie Leitch is pursuing the nationalist vote by going after immigration and suggesting people should have to take a "Canadian values" test before entering the country.

Michael Chong is running as a moderate Conservative in the upcoming leadership race.

The latter approach may go over well with some, Mr Woolstencroft says, but it would be "disastrous" in a general election. The Conservatives won their 2011 victory by convincing many new Canadians in suburbs of Toronto to vote for their economic policies. But in 2015, Harper lost many of those districts after campaigning on a platform for "old-stock Canadians" and creating a hotline for "barbaric cultural practices".

"They fumbled the whole issue in the last election, they were just awful at it. They seemed to be optically clueless," Mr Woolstencroft says.

Mr Brodie disagrees, and chalks the failures of the Conservatives in the last election up to their economic, not social policies.

"Trudeau presented a compelling economic message about Canada's place in the world economy, and the Conservative Party didn't," he told the BBC. In the last election, the Liberal Party extolled the virtues of spending on infrastructure and developing the high-tech industry, while the Tories economic plan floundered when oil prices tanked.

But their weakness in the last election could become their strength in the next, especially with Nafta renegotiations and an overheated housing market on the line, Mr Brodie says.

"But if we get into a big downturn, especially if the housing market turns south very quickly, I don't think there's enough there to show that the Liberals have a job creation idea, and that leaves their whole front and five flanks open," he says.

Although the party has a strong base in rural parts of Canada, the suburbs and western provinces, its base alone is not enough to win the next election, says Mr Brodie. Whoever wins the leadership better be able to make inroads in urban parts of Canada, like Vancouver and Toronto, or Quebec, where the party has typically had a small presence.

Maxime Bernier (L) is in the leadership race for the Conservative Party of Canada.

"It's easy for the Conservative Party to play on old values, but I don't think most Canadians are too wrapped up in that stuff," Mr Woolstencroft says.

But can the party grow its support in urban areas and progressive Quebec, without alienating their base? Maybe, both Mr Woolstencroft and Mr Brodie suggest, with a little help from the New Democratic Party (NDP).

In 2011, the NDP won the role of official opposition for the first time in party history when they took many formerly Liberal districts. Most of the seats they gained in that election reverted back to the Liberals in the 2015 election.

The left-wing NDP is currently in the middle of its own leadership race, but if it were to have a resurgence with progressive voters, it could help take seats from the Liberals or even flip some ridings to the Conservatives. They may stand a chance - many left-wing voters are frustrated that Trudeau has backed down on his promise for democratic reform and has continued to support oil pipelines.

"That's a possibility, short of that, it's going to be a hard slog and it's going to be well past my creativity to make that work," Mr Brodie says.

- Published22 February 2017

- Published18 October 2016