Chicago goes high-tech in search of answers to gun crime surge

- Published

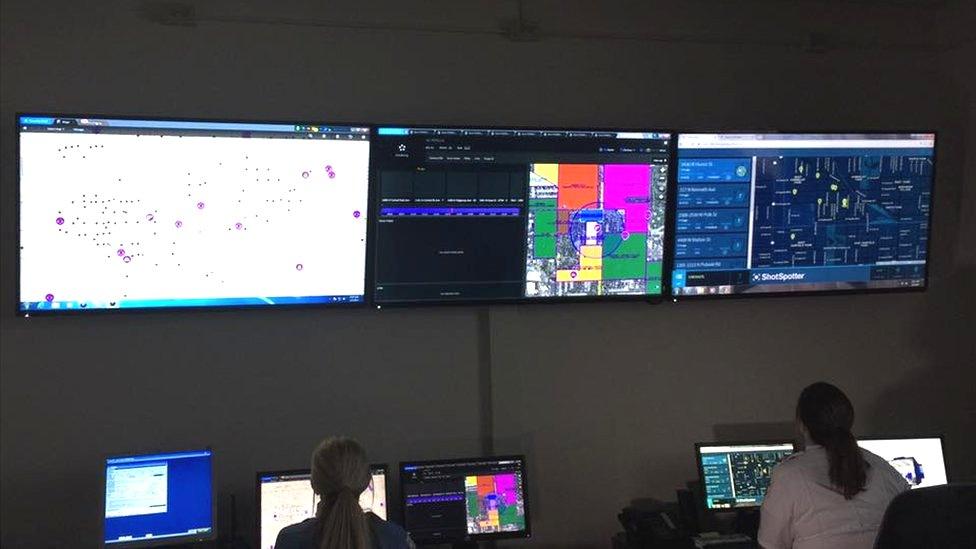

Analysts and officers track live crime data in Chicago's 11th police district

In a cramped office in a police station in Chicago's 11th district, the sound of gunfire is a little computerised ping that rings out a few times a day.

Somewhere in the district a microphone has picked up the percussive sound of a bullet and sent a signal, via California, to the station, which is where Kim Smith hears about it.

Ms Smith, a data analyst from the University of Chicago, works at one of the city's new Strategic Decision Support Centres, where data, technology, and old-fashioned police work are being combined in an effort to control a sudden surge in gun violence.

Seconds after a ping, a large flatscreen monitor displays a Google map of the gunshot location. Another connects to surveillance cameras activated by the shot, sometimes fast enough to see a gunman fleeing, and usually two or three minutes before the first 911 call comes in.

Sometimes someone happens to open fire while a live feed is rolling in the room. "I've seen a lot of shootings actually happen on screen in front of me," said Ms Smith, who was new to the world of law enforcement when she joined the project.

"The first time I was really shocked. You hear stories about people going out in the middle of the day in broad daylight, just walking the dog, and someone starts firing off rounds, but then to actually see it…"

Crosses for murder victims sit in an empty lot in Chicago's Englewood district

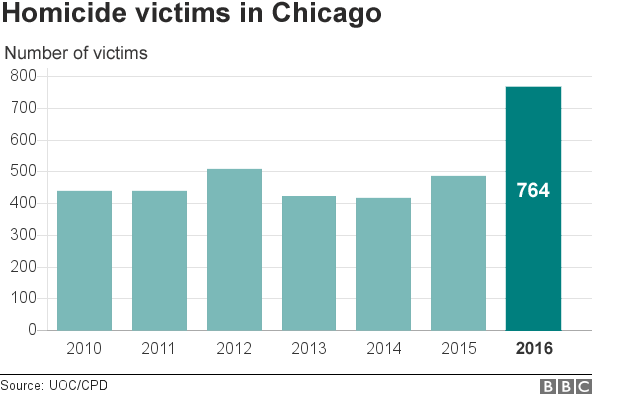

The strategic centres were established in February after more than 4,000 shootings and 762 homicides in 2016 - a massive 59% increase on the previous year and more murders than New York and LA combined. President Trump threatened in January to "send in the Feds" if the city didn't fix "the horrible carnage".

Taking blueprints from similar operations in LA and New York, Chicago PD set up two centres in the city's two most violent districts - Englewood and Harrison, which account for 5% of the city's population but nearly a third of all shootings last year. Eventually there will be six across the city, with initial set-up costs of about a million dollars each.

Chicago PD borrowed civilian data analysts - including Ms Smith - from the University of Chicago in an attempt to make better use of existing technologies like the Shotspotter microphones and more sense of the crime data routinely collected by the department.

The new cutting edge of anti-gun policing in Chicago had a modest start. The Englewood district centre set up shop in a disused line-up room, the partition wall and one-way glass knocked through to make more room. The first strategic meeting of the Harrison district centre was lit by a single lamp in a bare office.

Now there are large flatscreen monitors fixed to the walls displaying live maps and charts, while analysts track data on two or three screens in front of them. Each morning there is a strategic meeting where officers and analysts pore over maps and reports, attempting to predict trends or identify trouble spots.

Using a piece of predictive software called HunchLab, they translate the data into "missions", which can involve anything from talking to local business owners in certain areas to watching certain surveillance feeds at certain times.

And they might be getting results. The two pilot districts - on the South and West sides - have seen a 30% and 39% drop in gun violence so far this year, against a 15% drop city-wide. Chicago Police Deputy Chief Jonathan Lewin, who oversaw the development of the centres, said it was still early days.

"This is still a pilot so it's tough to determine causality," he said. "Is it the process, is it the technology, is it cars being more mobile because we're tracking them more rigorously? That's the million-dollar question."

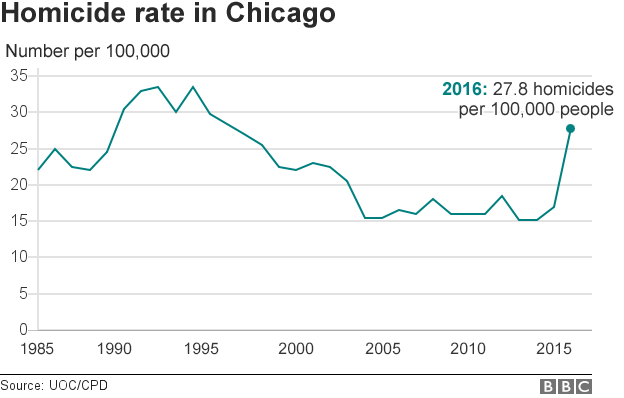

In reality, the stakes are higher than that. Chicago's murder rate soared last year, breaking 750 for the first time since the violent crime peak of the early 1990s and putting pressure on the police department to try new approaches.

There's no one easy reason for the sudden homicide spike. The murder rate is down so far this year compared with 2016, and still a long way from the violence of the early 90s, but the dramatic surge has made national headlines.

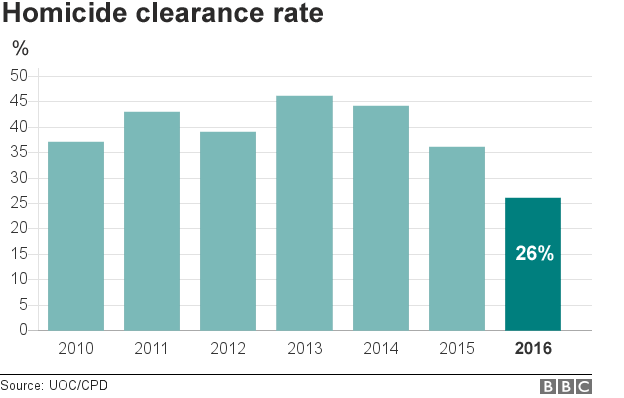

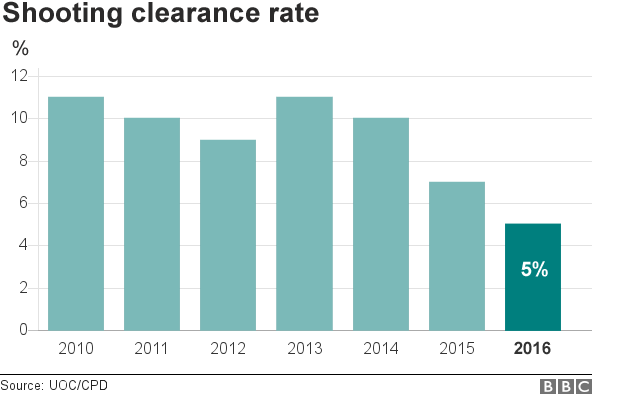

Jeff Asher, a crime analyst who has studied homicide rates in major cities, pointed to poor clearance rates, as well as a sudden and substantial decrease in street stops. The number of solved murders in Chicago fell to just 26% last year, according to analysis, external by the University of Chicago, compared with a national average of 62%.

"Chicago's murder clearance rate last year was abysmal," he said. "Gun violence begets gun violence, and if people believe crimes aren't going to be solved that increases the likelihood of retribution shootings and violence generally."

An 80% decrease in street stops between November 2015 and January 2016 has been linked to the November 2015 release of footage showing the controversial police shooting of teenager Laquan McDonald during a stop, as well as new laws on street stops introduced around the same time.

"Whether that played a role is difficult to say for sure," said Mr Asher. "But it suggests that policing matters, and that the degree of policing can have an impact on murder reduction."

Chicago PD has faced accusations that it turned to technology to paper over fundamental problems with community-police relations, strained further by the killing of McDonald. A Department of Justice report published in January accused the department of a pattern of racism and excessive use of force.

And surveillance is another concern. In a city which is already the most surveilled in the country, the number of police cameras in the two pilot districts rose by 25%.

"We can't use data and technology in a way that supplants suspicion for real evidence that someone is involved in a crime," said Ed Yohnka, a spokesman for the American Civil Liberties Union in Illinois. "Community-police relations are already poor in this city, and if the technology simply becomes a stand-in for community policing, then that's a problem."

This isn't the first time the department has turned to data to tackle gun crime. For about four years it has used a controversial secret list, based on a secret algorithm, to predict potential gun violence criminals and victims, angering civil liberties campaigners.

A report by research body the Rand Corporation suggested that the so-called "heat list" - which was recently made public for the first time - had no impact on homicide rates and actually increased the likelihood of arrest for those identified as potential victims.

Chicago mayor Rahm Emmanuel visits the Harrison centre

It isn't news to Chicago PD that there's a community relations problem. "A decade ago Chicago was recognised for its community policing and unfortunately we got away from that," said spokesman Anthony Guglielmi. "Every single district now has to refocus the way they think."

Part of that was under way with smarter policing, driven by the strategic support centres, he said. The next phase would shift focus to the community, including a programme that will put trainees into districts to forge community ties before they hit the beat for real.

"Don't mistake this for success, but it's progress," he said.

Others were less cautious. "I think it's made a huge difference already," said Kevin Johnson, police commander in the Harrison district. "Officers are more engaged, more involved, right across the department from patrol cops to narcotics to gang crime." And they had embraced the civilian analysts, he said. "I think we needed a different perspective."

Ms Smith is on indefinite loan from the university and plans to stick around as long as she'd needed. "It can be hard to gauge how much of an effect you're having," she said, "but think a lot of people have good reason to believe that what we're doing is making a dent on violence in Chicago this year."

- Published7 September 2016

- Published29 August 2016

- Published22 August 2016