Michelle Carter: What the texting suicide case tells us

- Published

How text messages led to a suicide

A Massachusetts judge has ruled that a teenage girl caused the suicide death of her boyfriend by encouraging him to end his life via text. What does this mean for the future of electronic communication and the law?

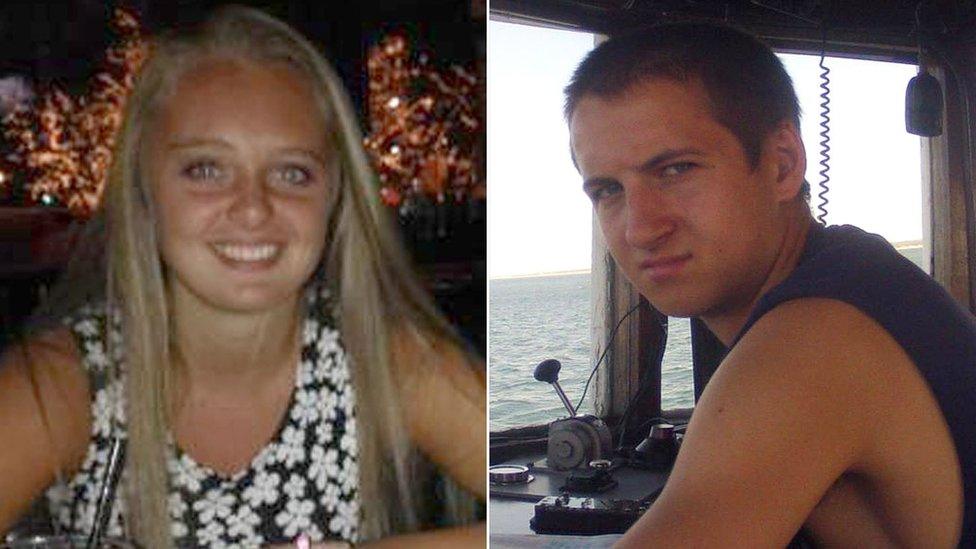

Michelle Carter was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter for sending 18-year-old Conrad Roy dozens of text messages that encouraged him to commit suicide. He died in 2014 of carbon monoxide poisoning, after he drove to a secluded parking lot and killed himself.

Many legal experts were surprised by the judge's decision, and say from the very onset this was a very strange case, compounded by intense media scrutiny.

"I would say from the very start, the charges were surprising," says Mary Anne Franks, a professor at University of Miami School of Law and vice president of the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative.

"There was so much anxiety and so much anger about what she did because her actions were reprehensible."

But apart from the public outrage, the case presented many tangled legal and ethical questions that troubled law experts, and the verdict could have important legal consequences for future cases.

1. The right charges?

Carter was charged with involuntary manslaughter, as opposed to a lesser charge like encouraging or assisting in the suicide of another person. That's because, while about 40 other states have a law similar to this on the books, Massachusetts does not.

"I've always thought manslaughter was an ill-fitting suit," says Daniel Medwed, professor of law and criminal justice at Northeastern University School of Law. "What Michelle Carter did was reprehensible, morally blameworthy and despicable, but I'm not sure it was manslaughter."

Medwed says the state essentially argued that causation took place - that Carter's texts caused Roy's death.

Carter sent Roy things like "All you have to do is turn the generator on and you will be free and happy," and allegedly called him to order him back into his vehicle when he got out.

But Medwed says that by the legal definition of manslaughter, those texts and the phone call fall short of proof of direct causation.

Franks wonders why Carter was not charged under Massachusetts' robust anti-harassment laws, with domestic abuse charges, or with failing to act when it was clear what Roy's intentions were.

She says she understands that the punishments for these lesser charges may have seemed to prosecutors to be insufficient, however, "to the extent that those are not robust enough [laws], we should be making them more robust, not using really extreme penalties and charges that don't necessarily fit".

Carter reportedly texted Mr Roy that his parents would "get over" his suicide

2. Can a text cause a death?

The verdict has puzzled and troubled some legal scholars because they says it essentially means that words themselves can kill.

"The real significance of the case is extending liability for creating risk based only on remote communication," says David Siegel, professor of law at New England Law Boston.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts has previously argued that this case has First Amendment rights implications.

"To take the view that the murder weapon here... was Michelle Carter's words - that is a quite aggressive view of causation," says Matthew Segal, legal director at the ACLU of Massachusetts.

"It's problematic to see prosecutors stretch the criminal law that much."

3. Does this set a precedent?

The trial verdict sets no immediate legal precedent, but if Carter appeals her conviction, it will begin moving up to Massachusetts' higher courts. If the highest court in the state affirms her guilt, the decision could have national implications.

"That would be landscape changing," says Franks.

In the more immediate future, Medwed says that other prosecutors could look to this successful outcome for the state as instructive and appropriate.

"I think it has some symbolic value," he says. "It could embolden prosecutors to be more aggressive with these cases."

That worries Segal, who says that it could affect a husband who - after a long, debilitating illness - talks to his wife about his desire to commit suicide, and then follows through by ending his own life.

"I gather it's the view of prosecutors in Massachusetts it's up to them whether she goes to prison or not," says Segal.

Mr Roy had been due to attend university in the autumn

4. Will this be a warning sign for how teenagers behave on their devices?

"No, I don't think so," says Rosalind Wiseman, an author who writes and speaks frequently about bullying, social media and teenage psychology.

"Young people, they tend not to look at situations and think it has anything to do with them until they're in a situation that may have some similarities."

John Palfrey, the headmaster of the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, a law professor and co-director of Harvard's Berkman Center for Internet & Society, says many adolescents feel an emotional disconnect when using their devices and will say many hurtful things they'd never say in person.

"I think the hard news for young people and their parents is things that young people do everyday on text or social media have extraordinary consequences - those can be life and death consequences, or that can be legal consequences," he says.

"Education is a slow process. I do think many students are getting the message and are being smarter about what they say to each other, but these cases are all too common."

Where to get help

If you are depressed and need to ask for help, there's advice on who to contact at BBC Advice.

From Canada or US: If you're in an emergency, please call 911. If you or someone you know is suffering with mental-health issues, call Kids Help Phone at 1-800-668-6868. If you're in the US, you can text HOME to 741741

From UK: Call Samaritans on 116123 or Childline on 0800 1111