Will we ever know what happened to Otto Warmbier?

- Published

Warmbier's roommate in N Korea describes the trip

When Otto Warmbier was buried in his hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio on Thursday, the story of how an apparently healthy young American man slipped into a coma in a North Korean jail probably went with him.

Warmbier was brought home to the US last week after 17 months in detention in the secretive state. His parents learned only shortly before his arrival that he had been unconscious for more than a year, and he died on Monday.

At his parents' behest, no post-mortem examination was performed. The coroners carried out an external examination and said radiological images and other medical records were being reviewed. Doctors at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center said they had found no obvious signs of physical abuse. An MRI showed severe brain damage consistent with heart failure.

The lack of an autopsy might seem strange, given the intense speculation over how Warmbier became so gravely unwell, but medical professionals said the procedure was unlikely to yield clues after all this time.

"An autopsy may show that the brain lacked oxygen for a period of time but it wouldn't necessarily tell us why," said S Andrew Josephson, director of inpatient neurology at the University of California at San Francisco.

There are some spontaneous medical situations that could cause that kind of oxygen deprivation, but they would be "extremely rare for a young, otherwise healthy person with no known cardiac or pulmonary conditions", Dr Josephson said.

A sudden heart arrhythmia or severe asthma attack that went untreated would be among the more innocent possibilities, he said. Some form of poisoning or asphyxiation among the more malicious.

Interference with the function of the heart or the lungs can be transient though, and leave no long-term marks either internally or externally beyond the damage to the brain. Doctors at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center said they found no obvious signs of trauma.

The North Korean account of events claimed that Warmbier contracted botulism, a type of poisoning caused by a bacterial infection, and was given a sleeping pill from which he never awoke.

Botulism could in theory cause extensive brain damage over time if it damaged a patient's ability to breathe alone, said Dr Eric Rosenthal, associate director of the Neurosciences Intensive Care Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, but only if basic treatment like a ventilator was not administered. "It's not something we would see in the US," he said.

The amount of time lapsed in this case would make it difficult to get to the truth, he said. "There are certain signs that can be recognised on an autopsy in the acute phase, but this far out it becomes exceedingly hard to be specific."

The chance of an answer from North Korea

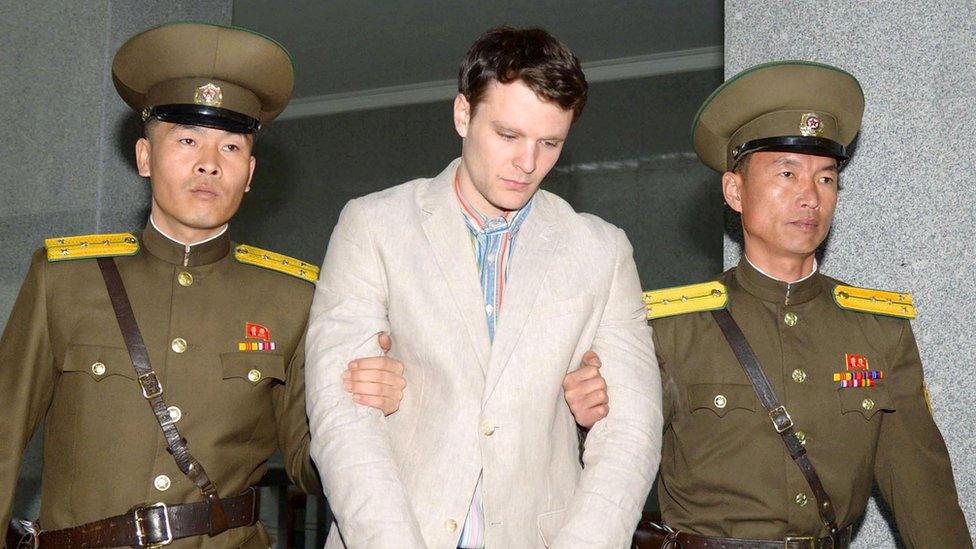

Warmbier was arrested in early January last year after removing a propaganda sign from the wall of a hotel. He was subjected to a sham trial and then a forced TV confession. According to North Korean officials, he fell into a coma shortly after that.

His family said they do not buy the state's account, and Warmbier's doctors in Cincinnati said they found no evidence of botulism in the young man. With his body now in the ground, the only explanation about what happened to him would have to come from the North Korean regime.

That is an unlikely scenario, said Aidan Foster-Carter, a Korea analyst at Leeds University. "The only way we would know for sure would be if someone directly involved were to defect and tell us, but even in those cases you can't always believe what people say," he said.

"And even if the regime produced something that purported to be an explanation of what happened, I'm not sure you could trust it."

For years North Korea denied any involvement in the disappearance of 13 Japanese citizens between 1977 and 1983. Then in 2002, in an effort to improve ties, Pyongyang admitted kidnapping the 13 to train North Korean spies on Japanese culture.

But doubts were soon cast over the regime's version of events. There was scepticism over the number of people abducted - with some Japanese estimates putting the figure as high as 60 - and over the real fate of the eight supposed to have died.

Japanese officials said tests on a jawbone and some ashes returned by North Korea as a gesture of goodwill, supposedly from a missing young man, showed they probably belonged to an elderly woman. North Korea said the victims had been buried, but that their graves were washed away by floods.

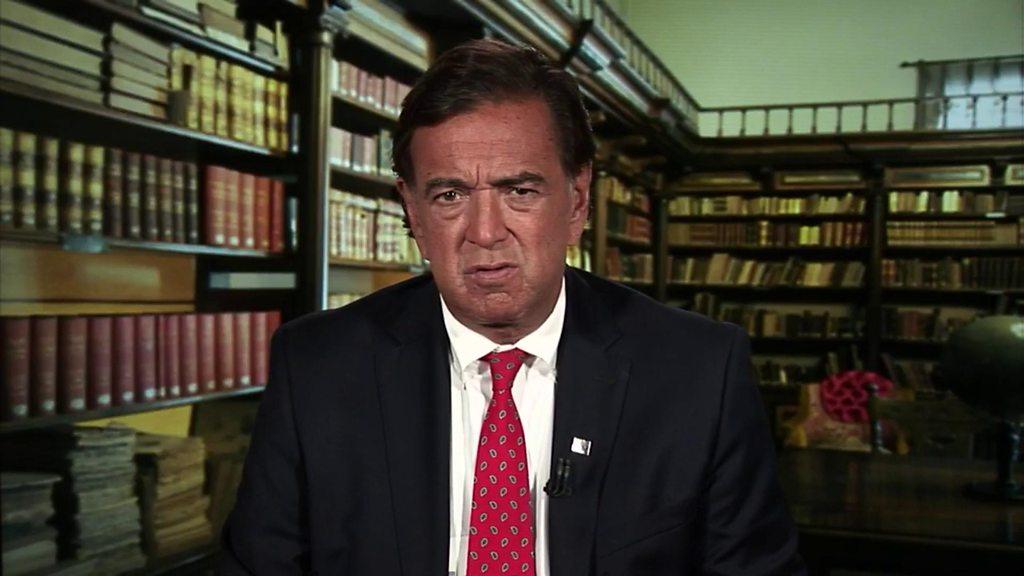

Warmbier speaks tearfully at a press conference in Pyongyang

Finding the bona fide truth about what happened to Otto Warmbier would probably require nothing short of the collapse of the North Korean regime, said Marcus Noland, a Korea analyst at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

"It would have to be like the uncovering of the Stasi files - a complete regime collapse, internal archives become available and someone gets hold of the Otto Warmbier file," he said. "Even if it were to come to diplomatic negotiations, the track record of the North Koreans providing accurate information is far from perfect."

President Trump has largely passed up opportunities to criticise foreign human rights abuses but he has put sharp focus on individual US citizens detained abroad. He called North Korea a "brutal regime" over its treatment of Warmbier and said the US would "handle it". Others went further. Republican Senators Marco Rubio and John McCain both said Warmbier had been "murdered".

But for all the outrage now, the issue is likely to fall down the list of diplomatic priorities once the news cycle moves on. "If and when serious diplomacy starts, all governments have to prioritise," said Mr Foster-Carter. Expending political capital on a dead man would be unlikely.

In a statement published after his death, the Warmbier family paid tribute to their son and mourned that they would never hear his voice again. An honest explanation of why he died now seems just as remote.

"I suspect the executive summary in this case is: we will never know," Mr Foster-Carter said.

- Published20 June 2017

- Published20 June 2017

- Published20 June 2017

- Published14 June 2017

- Published20 June 2017