My Canadian immigrant story: From the Philippines to small town Ontario

- Published

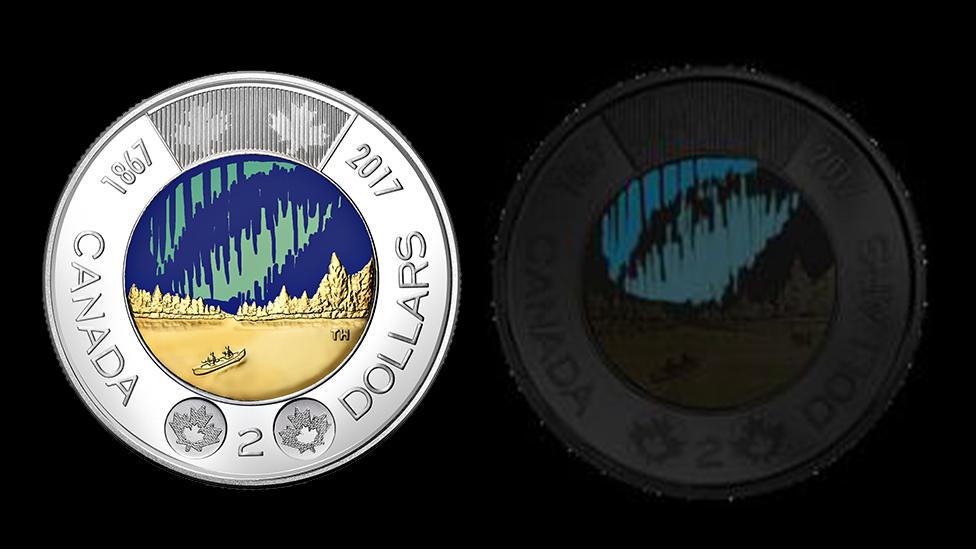

The Beboso family before moving to Canada

The BBC is launching a series looking at the immigrant experience in Canada and the important ties immigration creates between nations. We want to hear your stories and have a form to do so below. Our first story is about the connection between two families - one in the Philippines and one in Canada - even after more than 20 years apart.

When Aimee Beboso arrived in Canada aged 13 in 1993, she was expecting something different.

"We're going to America and we're going to a big city," she recalls, thinking of her family's move across the Pacific Ocean.

Instead, they landed in Timmins, a mining town of about 40,000 people in north-eastern Ontario.

There were no "big malls and skyscrapers" like she had seen watching the popular 1990s television show 90210 back home, Beboso says. "It was so, so snowy."

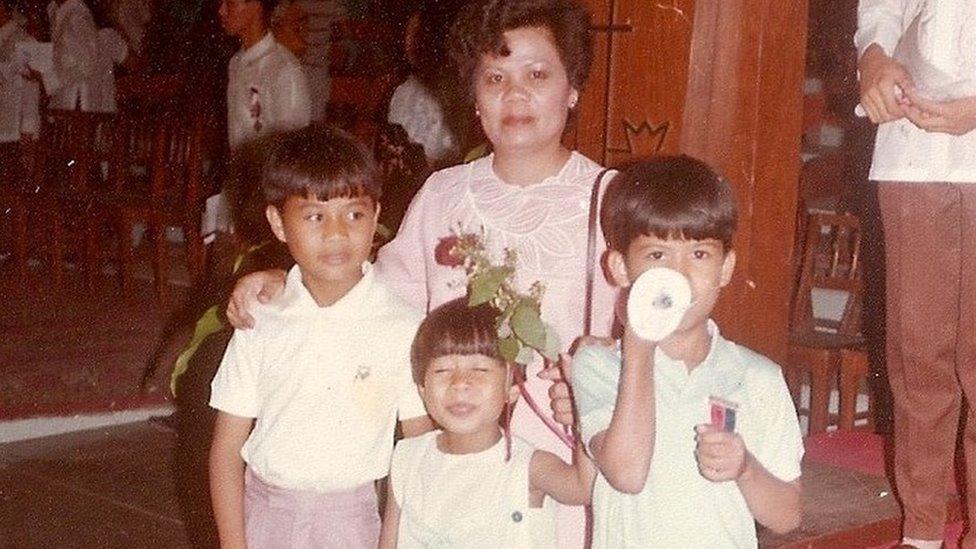

Beboso and her family were among the last of a group of extended family that migrated to Canada from the Philippines during the 1970s and 1980s. Three uncles, a grandmother and a cousin had already settled in Canada when Aimee and her family arrived.

More than 700,000 Canadians trace their heritage to the Philippines - one of the largest visible minority groups in the country.

Beboso's parents had moved their family of five to Canada so she and her older brothers could have a better education.

Aimee Beboso and her brothers in Timmins

The Bebosos had lived in a company town in the province of Negros Occidental, where many family members worked on a sugar estate. Sugar drove the region's economy - and exports had been slumping.

"Canada was viewed as a way out of the challenges," Maria Antonieta Beboso-Lopez, Aimee's cousin who stayed in the Philippines, says.

With so many family members overseas, Beboso-Lopez says, "we looked forward to every greeting card sent during birthdays and holidays with long letters, pictures and a few dollars tucked inside."

Beboso remembers her uncle collecting them at the Timmins airport when they first arrived.

She also remembers those early days of the family living in a cold basement with linoleum floors during a northern Ontario winter.

"It's just an open space. We used to have a house, you know?" she says of the family's middle-class life in the Philippines.

She and her brothers, 16 and 18 at the time, had only each other for company and two television channels - a point of contention for her teenage self.

"My expectation of the developed world was that we better have cable," she says.

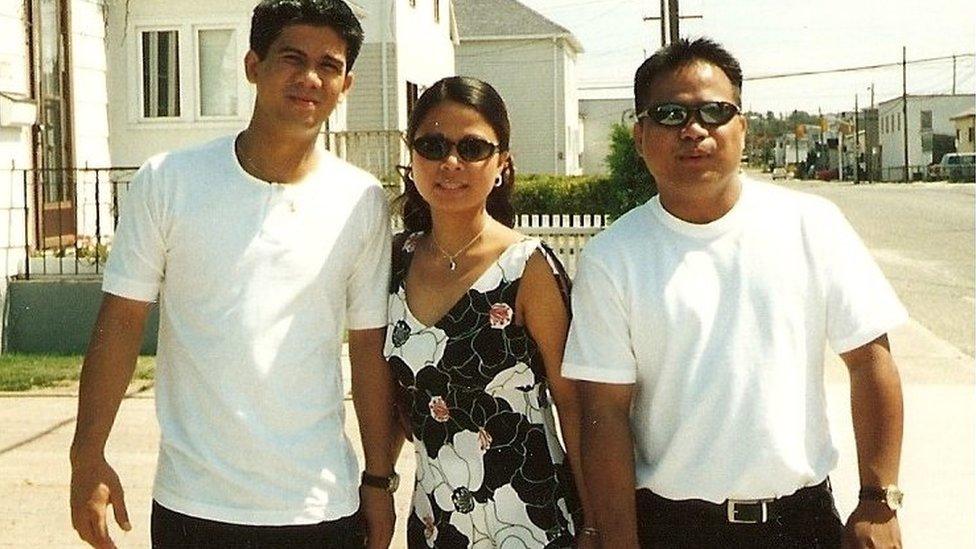

Aimee and her brothers pictured in front of their first house in Timmins

Her father was a trained machinist and could always find work, but the move was more difficult for Beboso's mother.

Her mother left a career as a respected private school teacher and her side of the family remained in the Philippines.

Like many immigrants, Beboso's mother struggled to get her experience and university education recognised. For a while, she flipped burgers.

"All of a sudden she had no resources," Beboso says. "I appreciate it more now."

At school, with her dark skin and hair, and as the only Filipina in her grade, Aimee stood out.

"They'd call me Pocahontas," she says.

Still, she managed to make friends quickly - especially when other students found out she was smart and that she would share her homework.

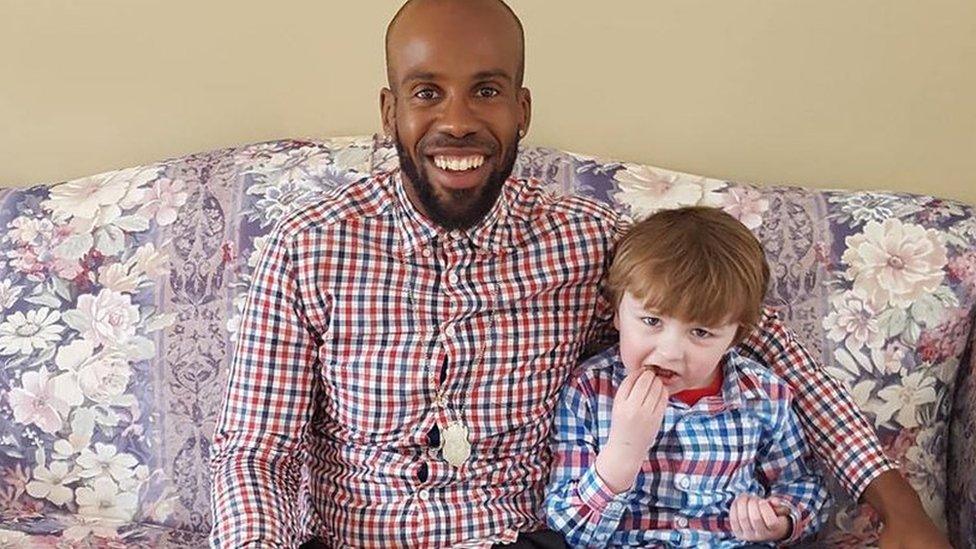

Beboso now works in Ottawa with the Philippine Migrants Society of Canada. Many of the people she helps are Filipino domestic workers and live-in caregivers.

Thousands of Filipinos have become permanent residents under federal government caregiver programmes that allow foreign workers a direct path to residency in Canada. Many are women and leave their spouses and children behind for years while they establish a life in Canada.

The highly popular programme has gone through various reforms in recent years and has experienced backlogs and application caps.

"What I've seen from my first-hand experience with these women is they're very hard working, survivors of migration," Beboso says. "I don't know how they're able to separate themselves from their children so they can work and send them money."

The government of the Philippines counts foreign remittances as a major economic boost for the country. Canada is one of a number of countries that plays host to migrant and working Filipinos, and those working and living abroad send home billions of dollars.

In 2014, the World Bank estimated residents of Philippines received about $2bn from Canadian remittances.

The Kanlaon volcano as seen from La Carlota town, Negros Occidental province

"Just like any typical Filipino family with relatives abroad," Beboso-Lopez says, they looked forward to goodies sent in annual "balikbayan" (homecomer) boxes. Family members also sent money for education and other needs.

Years ago, their families relied on hours talking on the phone to stay in touch.

Now the internet and social media are "the greatest blessings our family currently enjoy", Beboso-Lopez says.

Technology has brought them closer, she says, and given family in the Philippines "the opportunity to take a peek at their daily lives instantaneously" from thousands of kilometres away.

But their lives were also changed by immigration, even if they never left. "We are seven in the family and we are all degree-holders," Beboso-Lopez says.

There are two engineers, a computer science graduate and a hospital administrator. Beboso-Lopez was a journalist and is now a communication officer.

"And we owe it to the life offered by [Canada]."

For Beboso, she now calls Canada home. But she says when she went back to the Philippines a few years ago, "my heart ached a little bit".

"The food the people, the language. It felt the same," she says. "I just blended in."

- Published14 June 2017

- Published19 June 2017