Thunder Bay police under fire for indigenous deaths

- Published

Melissa Kentner and Barbara Kentner (right)

The death of an indigenous woman in Thunder Bay is the latest in a series of violent incidents affecting the local indigenous community. As the police ponder whether to charge her assailant with murder, many are wondering if the force has what it takes to pursue justice for all.

Barbara Kentner, an Anishinaabe woman, was walking down the street with her sister in January when she was struck by a trailer hitch someone had thrown at her out of the window of a car.

"Oh, I got one," her sister, Melissa Kentner, heard someone say.

The hitch struck Barbara in the abdomen and she was taken to hospital.

Shortly after, Thunder Bay police charged Brayden Bushby, 18, with aggravated assault. Over the next five months, Kentner lay in hospital, suffering from internal injuries and damage to her organs.

She died on 4 July at the age of 34.

Now her family and the indigenous community want to see Bushby's charges upgraded, and the driver and other passengers in the car charged as well.

Thunder Bay, Ontario

"I want them to be in jail and feel the same kind of pain I've been feeling," she says.

But a number of external reviews of the Thunder Bay Police Service, as well as decades of racially-motivated violence, have left many with considerable doubt.

"At this point in time, we don't have the faith in the Thunder Bay police to be able to conduct a proper investigation and a fair investigation," says Anna Betty Achneepineskum, the Nishnawbe Aski Nation Deputy Grand Chief.

Attacks like the one that killed Kentner are all too commonplace in Thunder Bay, says her childhood friend Deanne Hupfield.

The city of about 100,000 is one of the last urban outposts on the way to Ontario's vast north, which is mostly inhabited by indigenous people on reserves.

In 2011, 10% of the city's population had Aboriginal identity, compared to about 4% across the country.

Hupfield says throwing things at indigenous women "is a normal thing here".

"It happened to me growing up. It happened to my mom, my sisters and my friends." She says people would yell racial and sexual epithets and chuck beer cans, water bottles or trash at them.

One time, a man threw a crowbar at her sister in front of an undercover police officer.

Deanne Hupfield was a childhood friend of Kentner's.

The officer chased the assailant down, yelled at him and then returned, without taking the man into custody. The officer told her and her sister: "Don't worry, we scared them", she says.

When Hupfield was a teenager, she watched in horror as a group of cops beat up her cousin after the two of them had been arrested for joyriding.

Now an arts educator living in Toronto, Hupfield wants Thunder Bay police to address systemic racism in the force.

"They're not willing to take that hard look at themselves and acknowledge their own beliefs about us," she says.

Both Kentner's sister and Hupfield believe the attack on Barbara Kentner was racially motivated, and hope it is prosecuted as a hate crime.

But her death is not the first to strike the community.

In May, the bodies of teenagers Josiah Begg and Tammy Keeash were both found in local waterways.

In 2015, Stacey DeBungee, 41, was found dead in the McIntyre River. And between 2000 and 2011, seven indigenous students died after moving to the city to attend high school.

None of these deaths led to criminal charges; many were ruled accidental by police after brief investigations.

These 10 deaths are now the subject of a systemic review by Ontario's police oversight board, and its "ongoing concern" about how Thunder Bay police investigate the deaths of indigenous people.

The review was prompted by a 2016 coroner's inquest into the deaths of the seven students, which found that the cause of four out of the seven deaths was "undetermined".

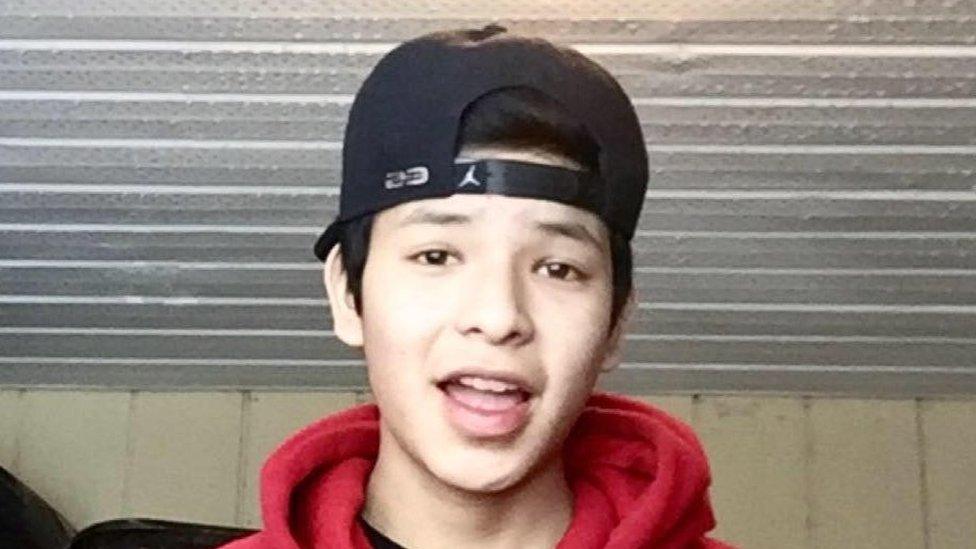

14-year-old Josiah Begg was found dead after disappearing while visiting Thunder Bay with his father.

Ontario's chief coroner, Dr Dirk Huyer, has also asked for assistance from an outside police force, the York Regional Police, in the ongoing investigation into the deaths of Begg and Keeash.

"When I looked at the investigations, I felt that there would be a benefit from some additional resources, another set of eyes, external perspective, to work together with the Thunder Bay police to really give us the best opportunity to give those answers," Dr Huyer says.

Chris Adams, a spokesperson for the Thunder Bay Police Service, says they welcome working with York police.

"We certainly supported it and we still do," he told the BBC. "It's really in the interest of finding answers."

Adams says the police is working on improving community relations, looking to a number of other communities to understand how they can improve their police force, including more efforts to recruit indigenous officers.

"We really recognise the need to have some reconciliation in that regard," he says.

Adams adds the force is working with Fort William First Nation to better understand some of the issues at play, and would welcome working with the Nishnawbe Aski Nation as well.

Meanwhile, Kentner's family is eagerly awaiting the result of the coroner's post-mortem. Police say they will wait for the results before deciding on whether they will upgrade the charges.

Barbara Kentner (right) with her cousin Debbie Kakagamic

Doctors told Melissa Kentner her sister died of liver failure exacerbated by the internal injuries she suffered during the attack, which included a ruptured intestine.

"Yeah, sure, she had problems with her liver," Ms Kentner says. "But she quit drinking and everything. She wanted to have that transplant."

She's sickened by comments on social media that disparage her sister's memory, saying Barbara was a "caring and loving person".

In her last weeks alive, Kentner knew she was going to die but hoped for justice, her sister says.

"She just wished that it never happened to anybody else."

- Published17 February 2016

- Published31 May 2017