Adam Maier-Clayton's controversial right-to-die campaign

- Published

Should people with a mental illness be helped to die?

A year ago, Canada legalised medically assisted suicide for terminally ill people approaching death. But one man's activism has forced Canada to ask difficult and controversial questions about the limits on an individual's right to die.

In the basement of his father's home in Windsor, Ontario, Adam Maier-Clayton lays out orange prescription bottles full of pills. They contain just some of the medication that doctors have given him to treat his mental health condition.

In a video posted on YouTube, he lists the anti-depressants, mood stabilisers and tranquilisers he's taken, as well as "lots and lots of therapy".

Adam's mental health problems first emerged in childhood. He suffered from obsessive thoughts, depression and anxiety.

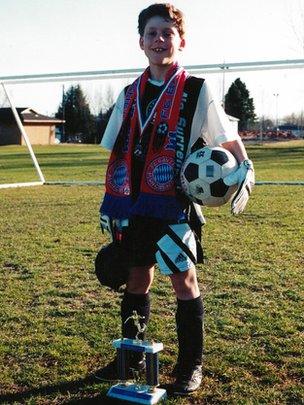

Later, as a talented soccer player and prolific goal scorer, he'd bind his fingers with tape to try to stop his physical tics from distracting him from his game.

But after experimenting with cannabis for the first time at the age of 23, Adam's symptoms worsened significantly.

"Man, it knocked him right off his tracks," his father Graham told me.

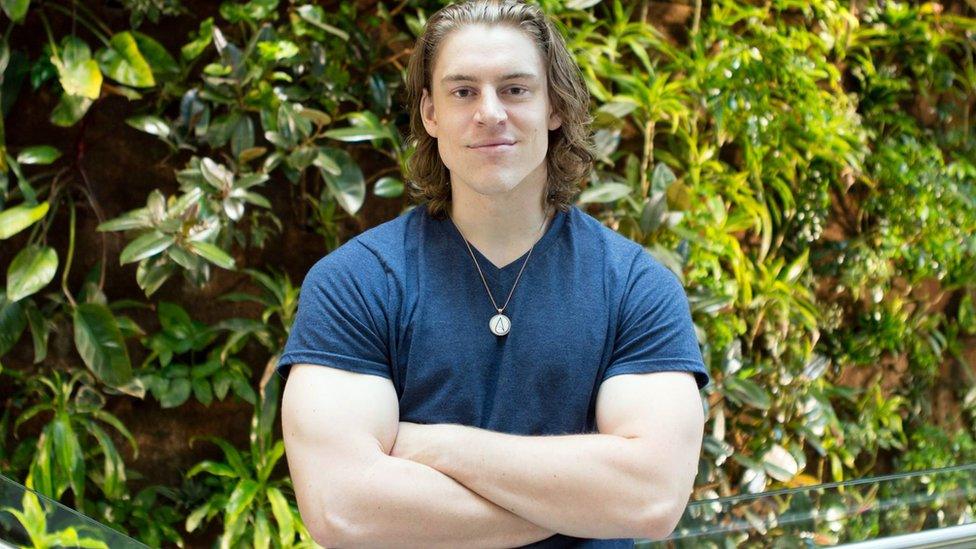

Adam Maier-Clayton campaigned for expanding the limits of assisted dying legislation

"He was in and out of hospital for six or seven days. He suffered depersonalisation, a kind of 'other worldliness.' Doctors thought it was just a temporary effect of the drug - but it brought about a permanent change in him and things started to go downhill from there on."

Adam began experiencing crippling physical pain throughout his body. He described the experience as akin to being "burned with acid".

Any kind of cognitive activity, such as reading, writing or even talking for more than a short time, made the pain worse and left him incapacitated for hours afterwards.

He was diagnosed with Somatic Symptom Disorder, a psychiatric condition characterised by physical complaints that aren't faked but can't always be traced to a known medical illness.

In June 2016, as Adam's bouts of pain were becoming ever more frequent and debilitating, Canada's federal parliament passed a landmark piece of legislation.

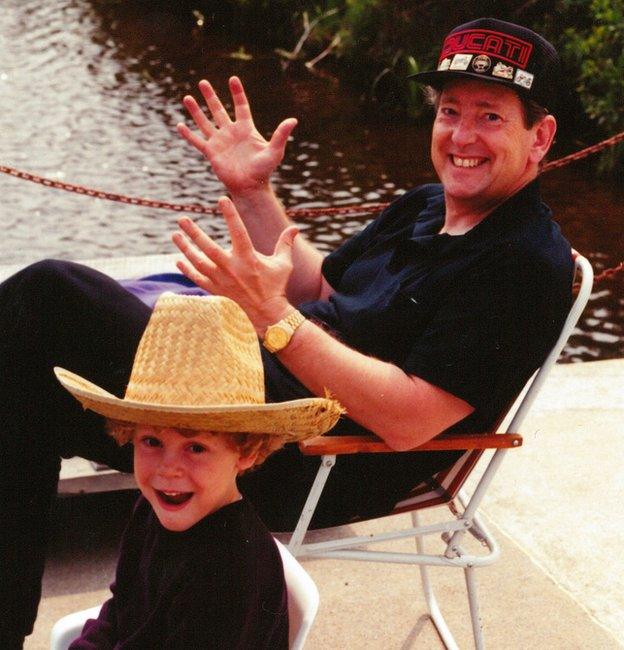

Adam Maier-Clayton and his father, Graham Clayton

The law is called Bill C-14.

It legalises physician-assisted suicide, provided certain strict criteria are met.

"C-14 allows people who are broadly conceived to be at the end of life, who are 18 years old or older, who suffer from a serious disease or disability, who have irreversible decline in capabilities and who suffer unbearably to obtain medical assistance in dying - basically a doctor or a nurse who will be able to end their lives," explains Trudo Lemmens, Professor of Health Law and Policy at the University of Toronto.

The boundaries permitting assisted suicide under Bill C-14 are deliberately narrow in scope - and exclude people suffering solely from a mental illness who aren't also grievously and terminally ill.

Adam Maier-Clayton believed the law was ambiguous, unconstitutional and discriminatory.

Convinced his condition was untreatable, he began a vocal campaign of media activism, arguing that Canada should follow the example of Belgium and the Netherlands.

In those countries, people who believe their lives have become intolerable because of severe mental illness can seek permission to receive lethal drugs with a doctor or nurse's help.

"Every Canadian deserves this right, the right to have the ability to terminate pain that is chronic, incurable," he told the Canadian Press in September last year.

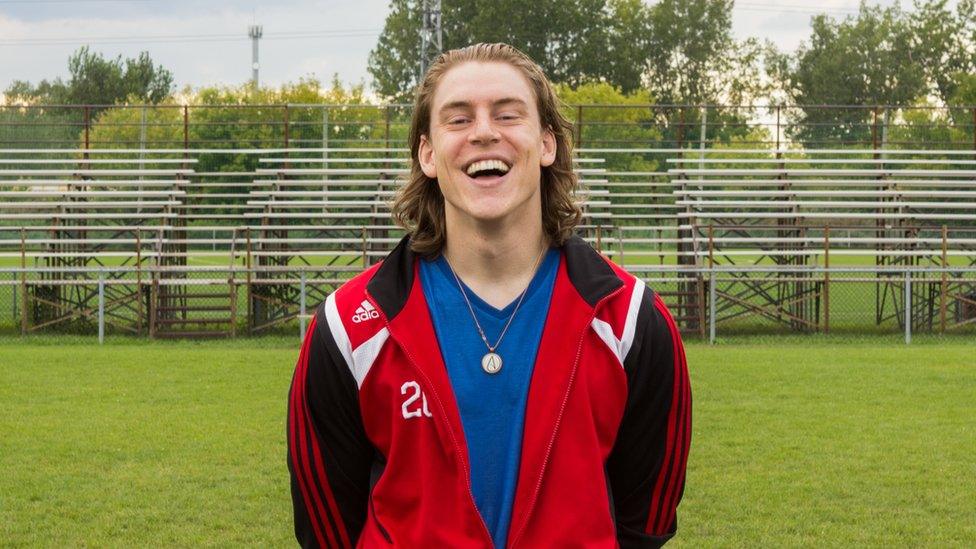

Adam Maier-Clayton was diagnosed with Somatic Symptom Disorder

But in cases of psychiatric illness, critics say, determining whether a person's condition is chronic and incurable isn't clear-cut.

"If we provide adequate mental healthcare, the majority of people will recover in a way that provides them with quality of life," argues Professor Lemmens.

"Yes, some people people will continue to suffer. Yes, some people will likely commit suicide - but at the outset we don't know who are the people who will not recover. That's very hard to determine."

'We need to be careful'

Dr Michael Bach agrees.

He's executive director of IRIS, a Toronto-based institute that works to improve the rights of people with disabilities.

He's not totally opposed to euthanasia, but fears a creeping inevitability should the criteria for assisted suicide be widened.

Once assisted suicide is made available to people with mental health problems, he says, more and more people are likely to be drawn to it before all their treatment options have been exhausted.

"To suggest that we can remediate suffering by terminating a life is a very strange logic," Dr Bach told me.

"We need to be careful not to provide an 'out' to tough situations.

"I don't want to say that we shouldn't do everything we can to minimise personal suffering. But we can't expect of medicine that we're going to eradicate suffering from life. Somehow that has emerged as the social and medical and political project."

The Supreme Court weighed in on medically-assisted suicide in 2015

Pro-euthanasia campaigners in Canada argue otherwise.

They point to a Supreme Court decision from 2015 in the case of Carter v Canada, which they say makes no reference to terminal illness as one of the core criteria for a medically assisted death.

"The Supreme Court justices in that decision could have at any time put 'terminal illness' or 'imminently dying' as part of the decision - they did not," says Shanaaz Gokool, chief executive of Dying with Dignity Canada.

"What they looked at was the person, and the level and degree of suffering that they may have, that may be physical or psychological or psychiatric in nature.

"And so from that decision our Supreme Court justices said that, yes, there is a role here to ensure that people who have grievous and irremediable medical conditions, that cause them enduring and intolerable suffering for which there is no remedy acceptable to the person as long as they're an adult and they're clearly consenting, should be able to have an assisted death," Gokool says.

Medically assisted dying for people with mental health problems is currently the subject of one of three reviews being carried out by the Council of Canadian Academies. A report is due before the end of next year, although its findings will be advisory and not binding on any future changes to legislation by Ottawa's lawmakers.

'I am my own saviour'

The review, though, will come too late for Adam Maier-Clayton.

On April 13th he drove to a motel just off Highway 401, ate breakfast, and then took his own life.

Adam Maier-Clayton excelled at soccer

He was 27.

In his final Facebook post he wrote: "I am my own saviour. Always have been. Always will be."

Following his death, Graham Clayton plans to continue his son's activism by campaigning for an extension of Canada's assisted suicide laws to include people with enduring mental illnesses.

"Adam didn't believe in suicide. He believed in suicide prevention," Mr Clayton told me.

"For the overwhelming majority of people there's hope. The research has been done. The medical treatment is there. If they have to go through a variety of different treatments and drug therapies to find what works, fine. Hang in there and stay the course.

"But when you know that you're in such a dire situation and the science hasn't been done it should be your call when you've had enough.

"If you're so inclined you should be able to ask for help - help in ending the pain."

Where to get help

If you are depressed and need to ask for help, there's advice on who to contact at BBC Advice.

From Canada or US: If you're in an emergency, please call 911. If you or someone you know is suffering with mental-health issues, call Kids Help Phone at 1-800-668-6868. If you're in the US, you can text HOME to 741741

From UK: Call Samaritans on 116123 or Childline on 0800 1111

- Published17 July 2017

- Published2 February 2017