As an open-air heroin camp is closed, options narrow

- Published

Addicts gather under the bridges along the freight track, away from the public eye

In a corner of Philadelphia known locally as the Badlands, where some of the purest heroin in the country can be bought for just $5 a bag, a half-mile stretch of rail track has become a refuge for hundreds of heroin addicts. Next week the city will begin to clear out the tracks, but where will the users go?

At the top end of Gurney Street in Fairhill, Philadelphia, there's a dirt path that forks through some trees and winds behind an old car repair shop, down to the rail tracks below.

Follow the path and you'll find a makeshift shooting gallery under a bridge, where heroin addicts gather out of sight and the ground is a sea of used syringes, cookers and needle caps. People stand around a wooden table to fix, tying on tourniquets and tapping in the crooks of their arms to bring up their veins. One man leans into a mirror to find a spot on his neck, carefully pushing a needle through the skin and rolling back into a chair, his eyes glazing over. Others line up along a long steel beam that forms part of the bridge, unwrapping fresh syringes and preparing to inject. For anyone too nervous, or too far gone, to find a vein, there's a man in a wooden shack a few metres away known as "the doctor", who will stick you for a dollar.

This is "El Campamento", the busiest and most built-up of a handful of hidden-away injection sites along a half-mile stretch of freight track between 2nd Street and Kensington Avenue. For more than 20 years homeless people and drug users have sought refuge in this gulch, and today there are about 70 people living along the tracks and up to 200 passing through every day to shoot up. As nightmarish as it feels, users here say it's a safe place, away from the police and the rest of the public, where people look out for each other and outreach workers visit regularly. Narcan - a nasal spray that reverses overdoses - is never far away.

But next week the city will begin to clear this stretch of track and force the users out. After months of negotiations between officials and rail company Conrail, contractors, guarded by police, will enter at the Kensington Avenue end and work their way up, disposing of an estimated 500,000 used needles, tearing down structures, and eventually paving over El Campamento and installing concrete rubble under the bridges to ward off new camps.

The city wants the rail company to put up prison-grade fencing around the tracks

Down by the tracks last week, news of the planned clearance was met with weary skepticism. "If they push us up from here you're gonna have a bunch of junkies on the streets looking for somewhere else to shoot up," said Luis, a 41-year-old father-of-two with dark, matted hair and dull eyes, who asked us not to use his real name.

Luis wakes up every morning in a rickety wooden shack and spends his days, like the doctor, injecting other users. The fee is one dollar or one sixth of a heroin shot, and most people pay in heroin. Every six injections Luis can do a hit of his own. For 22 months he was clean and clear of the tracks, until one day he came home to find his wife had suffered a heart attack in the bath and drowned.

Perched on a concrete barrier on Gurney Street, he squinted against the sun, opening and closing a flick knife in one hand and letting a cigarette slowly burn away in the other. "I had everything," he said. "I had a beautiful life, I had a beautiful wife, and in the blink of an eye it got took from me. That was a year and a week ago."

Days after she died he was back on the tracks. "At least down here you know you can get safe dope, you can get clean works, you can get high and nobody's gonna mess with you," he said. "If they board this up I have to start again. I have to find a new place I can lay my head at night where I don't have to sleep with one eye open."

Walking the half-mile length of track, under a blistering midday sun that baked the rails, person after person said they would simply find another hole in Kensington, the neighbourhood around the tracks — a place already gripped by poverty and overrun by heroin.

Life in a half-mile heroin encampment

Kensington was once a vibrant industrial area that people came to from around Philadelphia in search of work. As the manufacturing trades died away, employment rates and house prices plummeted, homes were abandoned and boarded up and the drug trade moved in. Now people come to Kensington from around the city, state and country in search of heroin. The area is said to be the largest open-air drugs market on the East Coast.

On nearly every block on the short walk from Gurney Street to Hope Park, dealers call out their brands — "So Fly", "Caution", "Cowboy" — and empty packets stamped with logos litter the way. The heroin sold here is among the purest, cheapest, and most lethal in the US. It courses through the veins of the place, turning public parks, churches, abandoned houses and street corners into venues to shoot up.

Before the deal was struck to clear the tracks, the city cleared out McPherson Square, a small park on Kensington Avenue that had become a haunt for addicts. At the centre of the square is the local library, and when national media reported in May that librarians were being trained to revive overdosed users in the square — rechristened Needle Park by locals — it was enough. The drug users were driven out.

"Back in '70 this was a beautiful park," said Joe Grone, a 53-year-old who moved to the edge of McPherson Square more than 40 years ago. He was pricked in the ankle by a used needle as he walked through the park last year, as was his five-year-old granddaughter as she sat on their front steps. "This place should be for kids, not for needles," he said.

Outreach workers fear users from the tracks will be pushed into abandoned row houses

Joe Grone was pricked with a used needle near his home on McPherson Square

Now a large mobile police unit sits near the middle of McPherson Square and officers roll around the perimeter on bikes. Last week, children were running around again, jumping through a sprinkler and screaming with delight. Save for the odd syringe cap nestled in the grass, it was a happy afternoon in Needle Park.

But drug outreach workers here question where the users went. Shortly after the square was cleared, there were reports that an abandoned church on Westmoreland Street had become a haven for addicts. Police moved in to clear the church too, and in the sanctuary, Kate Perch, a housing co-ordinator for local outreach charity Prevention Point, found a young couple in the grip of addiction. They had fashioned a makeshift home around a mattress and hidden their belongings under the organ pipes. As the police waited, the couple discussed different abandoned row houses in the area, debating which were safe.

"That's a conversation which will keep happening in this neighbourhood," Ms Perch said. "McPherson has been cleared, Westmoreland has been cleared, now the tracks are about to get cleared. What happens to these people when that site is no longer available? Where will they go that is safe?"

An abandoned church on Westmoreland Street which had become a haven for heroin addicts

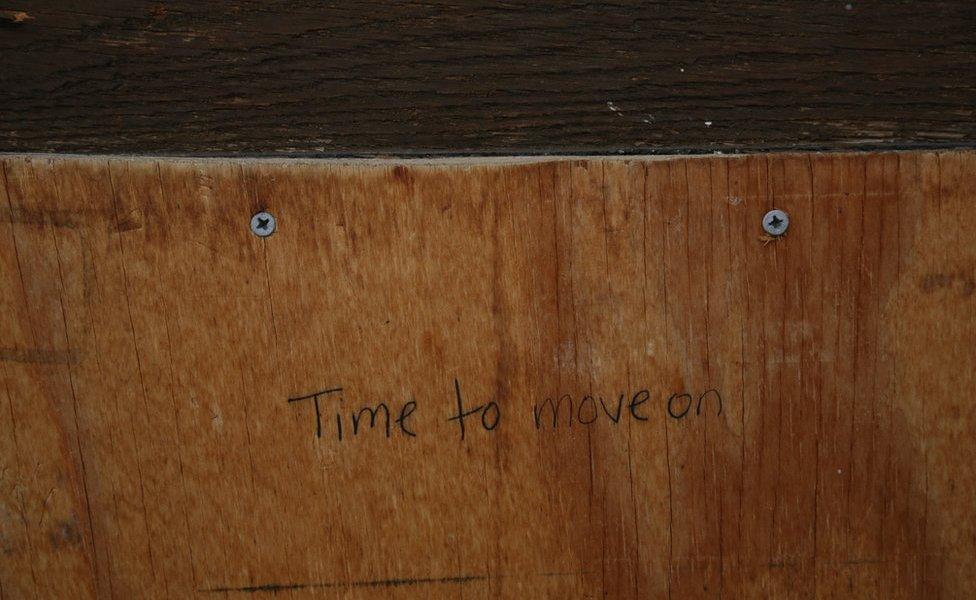

A message scrawled on the front door of the church as the users were cleared out

The worry for people like Ms Perch is that vulnerable users will be pushed into the city's hundreds of abandoned houses — "abandos" — where it is too dangerous for outreach workers to go, where people will overdose and no one will see.

The city is already predicting a 30% increase in overdoses this year, for the second year running, taking the grim toll from 900 to 1,200 - four times the estimated number of murders. Fentanyl — a tranquiliser 50 to 100 times more powerful than heroin which has been linked to deaths across the country - has taken hold, infecting the supply of heroin that floods into Philadelphia from the ports.

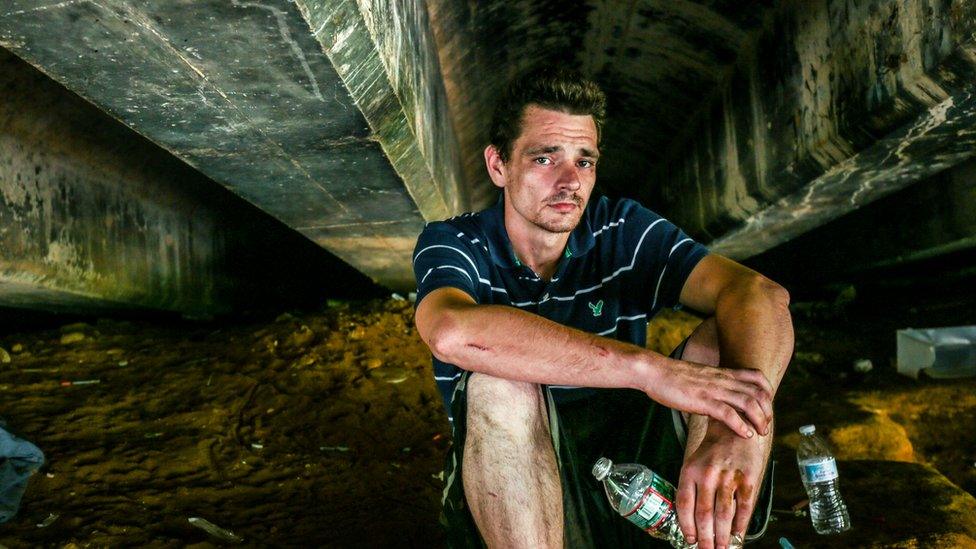

"The dope that's out there now... it's fentanyl, it's elephant tranquiliser, it's rat poison, stuff like that," said James Russell, a 30-year-old local with a 15-year heroin habit, who shakily made a cup of instant coffee as he waited for a check-up at Prevention Point.

"The way a lot of the fiends are here now, you hear someone shot a bag of dope and overdosed and seven out of 10 people rush to go find that dope. It's insane."

Jose Ojeda flew to Philadelphia full of hope. He came as an addict, seeking first-class treatment in the heart of the city. That's what they told him in Puerto Rico, anyway. But like thousands of others who had made the flight before him, he was heading for one of the city's unlicensed recovery houses, where users are exploited for their benefits and many wash out into the street, ending up places like the tracks.

"I'm searching for help but it's impossible for me because I don't have papers," said Jose, looking away as he spoke across an empty lot by the tracks, his eyes bloodshot, skin rough and needle-marked, one hand tightly cramped against his will. His ID was stolen with his wallet while he was passed out, he said. He thinks a lot about his mother who died in Puerto Rico while he was in Philadelphia, and about his daughter and his granddaughter who are still there.

"I'm trapped here now with my worn-out hands. I don't know how to speak English, I go places to ask for help and they don't understand me. It pushes me to drugs," he said.

Without ID he can't get treatment and he can't get home. At 42, he's stuck in Kensington, a long way from Puerto Rico, with a heroin habit he can't shake.

Jose Ojeda is one of thousands of Puerto Rican addicts who come to Philadelphia on a false promise of treatment

Even with ID, the barriers to treatment in Philadelphia are high. The city has an estimated 70,000 active heroin users and fewer than 15,000 treatment options at any given time, adding every different type together. The Housing-First programme will put a roof over the head of users without demanding they are clean, but there are currently fewer than 40 slots available in the Kensington area for about 400 homeless people.

The city has pledged an additional $250,000 to supportive housing and is planning a three-day "resources fair" on an empty lot on Gurney Street, to coincide with the track closure, but police will be in attendance and mistrust among users is endemic. Even if there were treatment options here for everyone, many in the grip of addiction are simply unwilling or unable to seek them.

"Addiction is a stigma driven disease in this country," said Roland Lamb, deputy commissioner at the city's Department of Behavioural Health and Intellectual Disability Services (DBHIS). "A person who is addicted only has about a one in 10 chance of getting the treatment they need."

Prevention Point's mobile needle exchange bus sits outside the old church where the charity lives

DBHIS is working with city-funded outreach groups like Prevention Point, in an attempt to engage with users before the track clearout. The charity began life 25 years ago as an underground needle exchange and two years ago moved into an old brownstone Methodist church in the heart of Kensington, a few blocks from the tracks. Hundreds of users travel to the building from all corners of the neighbourhood and beyond, for a check-up, a pack of clean needles or just a chat, and for a few hours every day the old church has a congregation of sorts.

"This place is a blessing," said Laura, a 41-year-old regular who endured 15 years of homelessness, drug addiction and prostitution before getting clean and finding a place in shelter. "When I first came here I was deep in my addiction," she said. "They save lives here every day."

But not everyone is grateful. Prevention Point has faced resistance from local officials and residents, who say it draws addicts to the area. The clean needles they give out undoubtedly save lives - HIV infections from drug use in the city have dropped from 50% to just 5% since the charity began its work - but some people were putting them to use immediately on the streets outside the building.

Jose Benitez is executive director at Prevention Point. "The community's approach is, 'We don't want this in our neighbourhood', the city's approach is, 'Oh my god something must be done'," he said. "The trick is, what's the something?"

As word spread that the tracks would be cleared, fear and anger began to surface in local Facebook groups. Philadelphia should "start executing drug dealers on the spot", wrote one resident. "Better solution, if someone comes into an emergency room full of heroin, let them DIE," wrote another. "DEAD IS BEST," someone replied.

The aggression worried Dan Martino, a part-time musician and local activist who volunteers with a grassroots group, Philadelphia Overdose Prevention Initiative (Popi). On the second Wednesday in June, Mr Martino went to Mick's Inn, a narrow, wood-panelled corner bar in Port Richmond, next to Kensington, where 30 or so local residents had gathered to discuss what would happen when the tracks were purged. After an hour or so of listening, he stood up to speak.

He asked the residents if they would be interested in a solution which would lower the death rate by 30%. They murmured yes. He asked if they would like to see lower crime rates and needles off the streets and they agreed. Then he said he was talking about safe injection sites, and the atmosphere in the room turned. Two women stormed out. When the meeting spilled into the street Mr Martino approached one of them. Her daughter had died of an overdose, and she told Mr Martino she would want to shoot anyone she found giving addicts a place to inject.

For some people around these neighbourhoods, safe injection sites — where users can test their drugs and inject in the presence of medical staff — are the last remaining hope. To others, they are unthinkable — a final nail in the coffin for a neighbourhood killed by heroin.

"We live in a world of heroin" - Dan Martino advocates for safe injection sites in Philadelphia

"When I first started advocating for this there was a wall of resistance. People who would yell at me like I've never been yelled at by adult," Mr Martino said. "But these people are going to use one way or the other. That's just the reality we live in. We live in a world of heroin. Until we can find a way to stop it coming in from the ports, this is what we have to do."

The woman who stormed out of the meeting was Kathleen Costello Berry, a lifelong Port Richmond local whose daughter overdosed at just 17 and was left in a hospital parking lot to die. "I just had to leave, I couldn't even listen to him speak," she recalled.

"I lost my daughter. If anyone had dared to tell me she could come somewhere safe to shoot up and we'll keep an eye on her…" She trailed off, her voice cracking. "No. No way. There is no safe way to shoot poison into your veins."

There are no safe injection sites in America, yet. As the nation's opioid epidemic spirals, several major cities, including Seattle, San Francisco, and New York, are beginning to consider taking the leap, but there is fierce political resistance to the idea.

There is one such site in Canada though, in Vancouver, and statistics suggest it has stemmed the tide of dead bodies there. More than 700 injections take place every day in 13 mirrored booths and no one has died at the facility since it opened in 2003. The clinic estimates that it has prevented 5,000 fatal overdoses. But the then-Conservative government fought it all the way to the Supreme Court.

Users shoot up at a safe injection facility in Vancouver

In Philadelphia, a new opioid task force will "further explore" the possibility, said a spokesman for Mayor James Kenney, citing "serious legal, practical, and law enforcement issues that have to be considered" first.

Some local officials remain opposed. "It's taken a long time for us to hit rock bottom here," said Maria Quinones Sanchez, councilwoman for the city's 7th district, which encompasses Kensington. "Do we want to now send a message that you can come here and buy the cheapest drugs available and then actually have a place to use them?"

But the current strategy - clearing out one park, church, or railway gulch and pushing people to the next - doesn't appear to be working. It has created a grim merry-go-round in Kensington that threatens to cause yet more lonely deaths. Consumed by addiction, and unready for treatment, most people along the tracks will continue to slip through the net.

"Heroin is what's killing people, but not giving people the opportunity to say help me, not giving people the opportunity to seek treatment - that keeps them in the basement, it keeps them in places like the tracks," said Mr Martino.

"These people don't want to die, despite their best efforts. They don't want to live like this."

"If we get pushed out of here I'll use right on the street", said Mark Vallotta, 39. "I got nowhere else."

A tattoo points towards an old needle scar

Down at the tracks last week, life was going on as usual. After so many delays, few people seemed to believe that the bulldozers would really roll through. But the rail company's deadline to start work is the end of the month, and the city has had enough.

Luis was still injecting people and getting high off the profits, enough to dull the pain of the anniversary, a few days earlier, of his wife's death. He couldn't see a way out.

"I'll just try and break through the fence and come back in," he said. "I ain't got no place else to go. It's here or nowhere."

A few feet away under the bridge, by the fixing table, another user, Manuel, shifted his weight from foot to foot and stared off into the distance, pushing a baseball cap absent-mindedly up and down his forehead. He recalled doing his first ever hit of heroin, years ago, by the tracks. "This is where I started, it's the only place I've ever come to," he said. "If this place wasn't here maybe it would be easier for me to stop.

"It's like my legs carry me here by themselves. If they close down these tracks, I dunno. I hope my legs take me somewhere better."

Photographs by Hannah Long-Higgins

- Published3 May 2017

- Published14 November 2016

- Published10 March 2017