Nafta talks: The view from the free trade front lines

- Published

Some 8,000 trucks cross the Ambassador Bridge daily

As Canada, the US and Mexico prepare to sit down and renegotiate their trade deal at President Donald Trump's request, unease has enveloped a motor industry town in Ontario which finds itself on the front lines of this battle over North American trade.

Every day some 8,000 trucks travel the 2.8km (1.75 miles) between border checkpoints at Windsor, Ontario, and Detroit, Michigan, under the steel arches of the Ambassador Bridge and over the Detroit River.

The 88-year-old bridge - the busiest border crossing by trade volume in North America - is a vital link between the two countries.

It connects industrial nerve centres in each country, feeding highly integrated cross-border supply chains.

And each day, trucks from Laval International, a 42-year-old compression mould making company based in Windsor, come and go across the span.

Company president Jonathon Azzopardi has a message he'd like to deliver to Donald Trump, as Canada, the US, and Mexico prepare to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta).

"Canada, of all three of the partners, is the only one that fulfilled its obligations," he says.

"You didn't fulfil your promises. We did."

On 16 August, the three trading partners will sit down in Washington, DC, for the inaugural round of talks launched at US President Donald Trump's behest.

Mr Azzopardi says Canadian companies like his have invested in the American and Mexican economies, creating jobs and helping to sustain communities.

"Did we profit from it? We grew, yes. But did we also reinvest? 100%. They can never take that away from us."

He says he'd be "hard pressed" to find the same number of American and Mexican companies who did the same for the Canadian economy.

The Windsor, Ontario skyline seen from across the river in Detroit

In Windsor, where so many livelihoods and companies depend on Nafta, people are feeling wary, says Keith Henry, president at Windsor Mold, a tooling and automotive components company with divisions in Ontario, Michigan, Ohio, Tennessee and Mexico.

"The Nafta uncertainty is just causing - has caused - everybody to just pause because they don't know where to invest, they don't know what's going to happen," he says.

They hope legislators on both sides of the Canada-US border understand the vast and dynamic market that has grown within Nafta, which formed the world's largest free trade zone when it came into force in 1994.

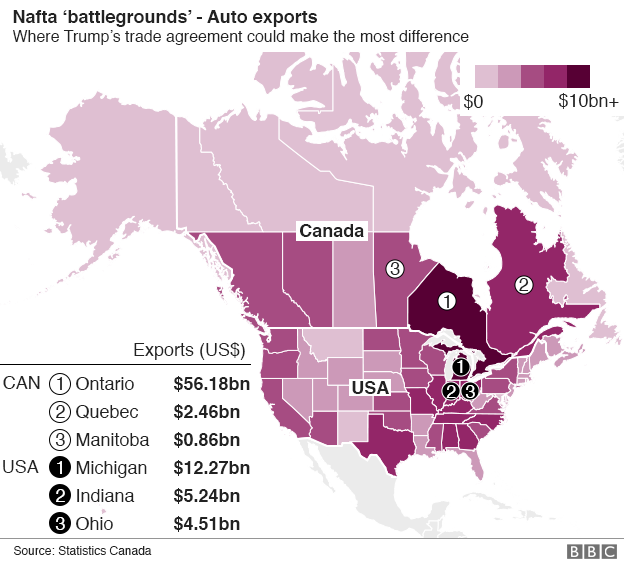

Nafta's battlegrounds

Canada is America's second largest trading partner. In 2016, more than $540bn-worth of goods passed over the border, from avocados from California to petroleum from Newfoundland and Labrador.

But while trade between the two countries is integral for both economies, manufacturing is heavily concentrated in specific regions and industries.

Almost 40% of all US goods sold to Canada comes from just five states: Michigan, Ohio, Illinois, Texas and New York, and is concentrated in just a few industries such as automobiles and machinery.

In Canada, Ontario produces about half of all goods sold to the US and much of its products are tied up in the auto industry. All in all, the auto industry in Ontario and Michigan alone is responsible for about 12% of all trade between the two nations.

The Windsor-Detroit region is one of Nafta's epicentres.

Windsorites see their town as a Detroit suburb, sharing a vital auto industry with Motor City.

The big three - General Motors, Ford Motor Company, and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA) - have had their headquarters in Michigan. Ford and FCA have operations in Windsor, helping generate around 20,000 jobs.

Windsor is also a hub to move goods, services, and people across the border.

Almost 17% of all Canadian exports end up in Michigan. Over 10% of Canada's imports from the US come from Michigan.

Because the border is so close and convenient, over 6,000 Windsor residents cross each day to work in the US, under Nafta provisions for professional workers.

Mr Azzopardi didn't always support Nafta.

He remembers his father, the company founder, coming home and warning the freshly-inked trade deal was a job killer, a disaster for the Canadian economy and exporters like him.

Mexico had cheaper labour and could make cars for less. There were a couple of years of struggle in Windsor.

But the region's manufacturers learned how to compete, becoming suppliers within the integrated continental market.

"We've expanded to Mexico, we're growing together," says Mr Azzopardi. "That's the secret sauce that people don't see."

As the big three auto makers expanded operations into Mexico, their clients - companies like Laval International and Windsor Mold - expanded with them.

Says Keith Henry: "We didn't put a plant in Mexico to take advantage of cheap labour and make parts there and ship them back to the United States and Canada."

"We located in Mexico because our customers were expanding their business operations in that country."

Zekelman Industries is the largest independent pipe and tube manufacturer in North America, producing 2.5 million tons of pipe and tube annually in 15 manufacturing plants in the US and Canada.

The company's products can be found in the the roof of the Skydome, where Toronto's popular baseball team - the Blue Jays - plays.

Barry Zekelman of Zekelman Industries

The company also produced 125,000 tons of hollow steel structural tubing used in the security fence along the US-Mexico border.

CEO Barry Zekelman understands the resentment in US Rust Belt states like Michigan, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Wisconsin that helped propel Donald Trump into the White House.

He's ready with a quote from another US presidential candidate, Ross Perot, who warned in 1992 that Nafta would result in the "giant sucking sound" of American jobs heading to Mexico.

"That's exactly what happened," he says.

"You have communities that you drive through, you go through these towns and they've disappeared. "

Mr Zekelman understands why the Trump administration has targeted the $63.2bn trade deficit the US has with Mexico, and doesn't think that the White House takes real issue with Canada as a partner.

"Trump's a big personality and that style rubs a lot of people the wrong way," he says.

"But he's there. He's president and you have to learn how to deal with it. So everyone needs to calm down. I don't think he has any animosity towards Canada."

It's a belief bolstered by comments the president made to his Mexican counterpart.

According to a leaked transcript of a January phone call recently published by the Washington Post, external, Trump told Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto that: "Canada is no problem - do not worry about Canada, do not even think about them. That is a separate thing and they are fine and we have had a very fair relationship with Canada".

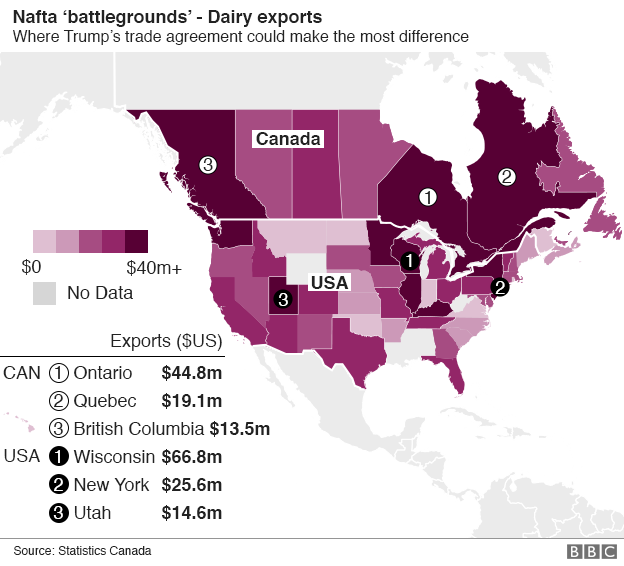

In July, the US set out its broad negotiation objectives for the talks, which include reducing the US trade deficit and improving market access in Canada and Mexico for US manufacturing, agriculture, and services.

Canadian industries in the US sights include dairy, wine, and grain.

Trade-dependent industries worry about who might become pawn in the negotiations, unsure what might be traded for more access or to protect another industry.

Canada's economy is hugely dependent on trade with the US, with over 75% of its exports heading south across the border.

The trade pact opened up new export opportunities, helped businesses become globally competitive, and brought in foreign investment.

But it's not an entirely a one-way street.

Canada isn't without leverage, says Lawrence Herman, with the CD Howe Institute, an economic think tank.

"We purchase selected products, we're a major market for so many states. The Midwest is highly dependent on trade with Canada. There are pressure points."

Almost 9m American jobs are dependent on trade and investment with Canada.

Dairy wars: Why is Trump threatening Canada over milk?

It's that message Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's government has been bringing to American lawmakers.

Over the past few months, ministers, provincial premiers and even city mayors have beaten a path to the US to plead the pro-trade case.

Industry and lawmakers from US states that count on the agreement being there for business have also warned the administration to tread carefully in the Nafta renegotiations.

In Canada, there is no dispute that the US economy has to be sound. The country depends on its 320m consumers.

"If the US (economy) catches a cold, we die of the flu. And we shouldn't be ashamed to say that," says Mr Azzopardi.

"Just because we're the little brother doesn't mean we don't contribute. We contribute a lot."

Data reporting by Robin Levinson King

- Published14 July 2017

- Published19 April 2017