Cuba acoustic attack: What is a covert sound weapon?

- Published

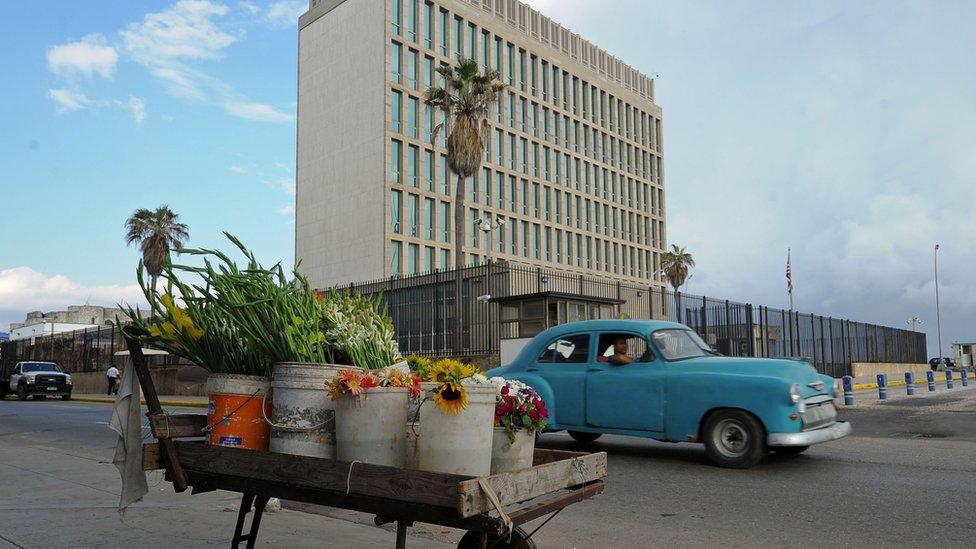

At least 16 staff members at the US Embassy in Havana have reported symptoms blamed on an "acoustic attack"

The US state department says its diplomats in Cuba have been suffering symptoms including hearing loss after suspected sonic attacks, some of which were - according to some reports - inaudible to human ears.

The use of sound as a weapon is not new, but what about unheard sound attacks?

What damage can sound do?

If you've ever heeded the warning to wear ear plugs to a loud concert, you have been taking care of the hair cells in your inner ear that pick up noise and send it to the brain. You've been trying to avoid hearing loss or tinnitus (ringing in the ears).

But sound can have effects that go beyond hearing.

Symptoms of a sonic attack may include dizziness, headaches, vomiting, bowel spasms, vertigo, permanent hearing loss and even brain damage.

How would an inaudible sound weapon work?

There are two options - go low or go high.

Lower frequencies than humans can hear - below 20Hz - are known as infrasound. They're used by animals including elephants, whales and hippos to communicate.

Infrasound could affect human hearing if very loud, and could cause vertigo and even vomiting or uncontrollable defecation if deployed very intensely.

But Dr Toby Heys has told the New Scientist, external that an attack using infrasound would rely on "a large array of subwoofers" and "wouldn't be very covert".

Given the Associated Press, external reports embassy staff were targeted at their residences, it's hard to see how anyone would pull that off without the huge racks of speakers giving the game away.

Ultrasound frequencies above 20,000Hz, or 20kHz, are also inaudible to humans but can damage the parts of the ear, including hairs, that pick up sound.

This is more likely in the Cuban case as ultrasound can be targeted more easily. It has many medical applications so has been at the forefront of research, and directional speakers already exist for home use. These could direct sound through walls.

But any equipment would need to be reasonably large to fit a battery that could power it strongly enough, and an ultrasound attack would place other people in the vicinity - including, potentially, the person carrying out the attack - at risk.

Steve Goodman, author of the book Sonic Warfare, told BBC Radio 4 that it was "not clear" whether inaudible soundwaves could give someone the hearing loss the state department described.

"The information given is so vague it's hard to say," he said.

Who has this kind of technology?

Again, it's not clear. And it's also not clear who would have carried out such an attack on embassy staff. Cuba has denied involvement and security analysts say it may have been done by a third country, hostile to the US.

Elizabeth Quintana, a senior research fellow at the UK-based military think tank the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), specialises in emerging technologies in the defence world.

"The US have been surprised at the extent to which others have caught up with them in all sorts of technologies," she told the BBC.

"It's probably not so much a surprise that the technology exists, more that others are aware of it and using it."

Has sound been used as a weapon before?

Yes. Sound cannon are used in crowd control by police forces around the world, were fitted to a ship, external to deter Somali pirates, and were made available for London police during the 2012 Olympics, although not used.

Some versions are capable of producing deafening sound levels of 150 decibels at one metre. They can deafen people within a 15 metre range and some can be heard miles away - not quite the subtle, covert operation supposed to have happened in Havana.

Police in the US have access to Long Range Acoustic Devices, a form of sonic cannon

Sound has been used in psychological operations too - the US army played heavy metal and Western children's music, external to Iraqi prisoners of war in an attempt to deprive them of rest and make them co-operate in interrogations.

And some shop owners in the UK use so-called Mosquitos, devices that emit high-pitched sounds (15-18kHz) and cannot be heard by people who have turned 25, to try to discourage teenagers from standing around near the entrance to their shops.

But in all of these examples, the person being targeted could hear the sound - a key difference from the incidents said to have happened in Havana.

- Published25 August 2017

- Published11 December 2012