Do 'Pray for...' messages make disaster relief harder?

- Published

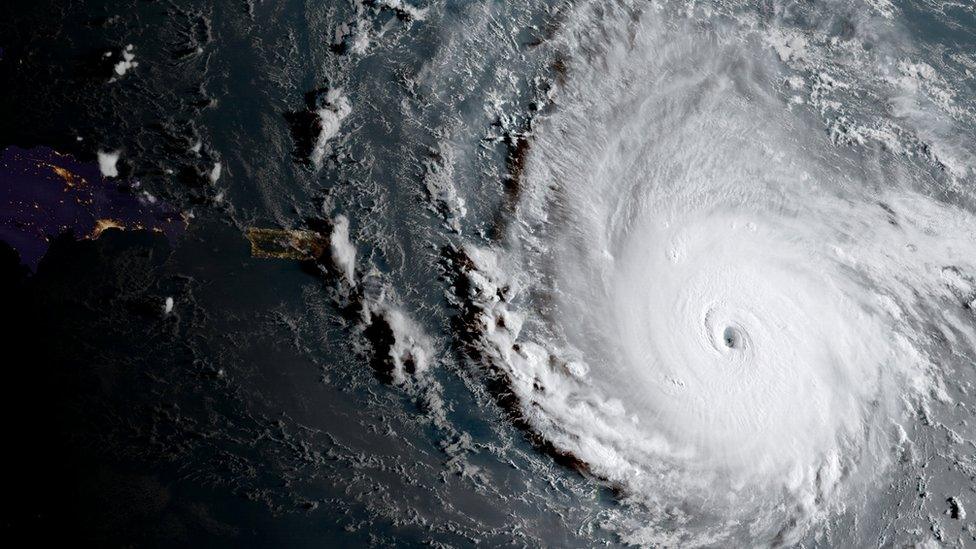

Volunteers used social media to coordinate rescue efforts during Hurricane Harvey

More than 1,000 people asked Magan Flores for help during Hurricane Harvey, despite the fact she had no formal training or official role in the emergency response.

"I remember people just calling in pure panic, and me, trying to hold it together for them, trying to tell them to stay calm," she told the BBC.

Magan was in Dallas, which is over 200 miles (320km) away from Houston where the flooding was most severe. But when she saw people needed help she posted her details on social media and offered to put people in touch with rescuers on the ground.

"People couldn't post their information to get rescued. So I hopped on and offered them to text me the info," she says. Magan used Facebook, and a walkie-talkie app called Zello, to send the locations of people who needed to be rescued to volunteer rescuers who were patrolling Houston by boat.

Before long she was receiving roughly 10 calls a minute from people who could not get through to the emergency services.

"You could hear the water rushing, babies in the background crying, and the pure sound of fear in their voices," she said.

Magan Flores helped dispatch rescue boats during the Houston floods

But her work was made more difficult by the massive amount of activity on social media during the storm.

"The Facebook page became an issue when non-essential posts were clogging it up. As much as we would've liked to have answered every post that came through, it was impossible," she says.

"At one point, in the middle of Harvey, we had issues accessing the page in general and had to turn it off so that we were able to review the posts and pin locations."

So does the huge surge in non-essential posts during these disasters cause more harm than good?

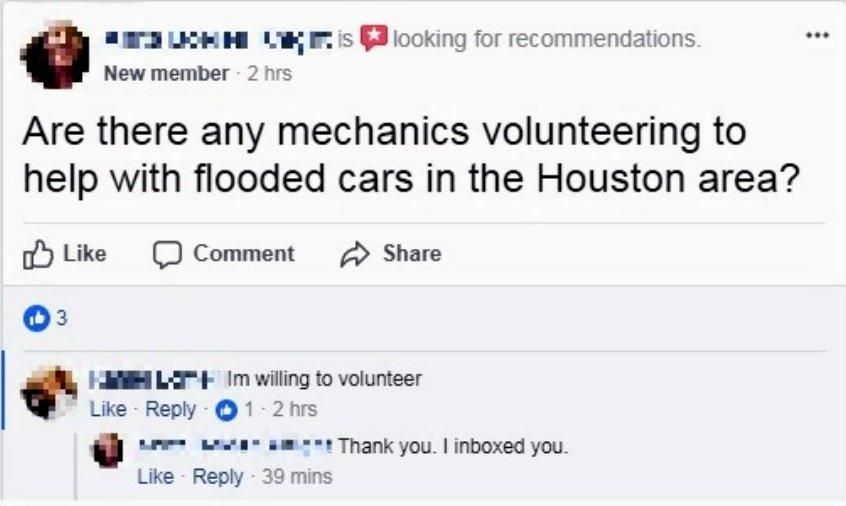

Facebook groups with thousands of members were used to offer support during the hurricanes

Patric Spence, an associate professor at the Nicholson School of Communication at the University of Central Florida, believes so.

"At one point during Hurricane Sandy, there were over 12.5 tweets per second sent using the hashtags promoted by the official response agencies. Finding useful information within the information glut of countless people communicating on the subject can be difficult," he said.

The massive number of people posting during a disaster - often using the same dedicated hashtag - can make it more difficult to find important information that can ultimately save lives. But Professor Spence warns that people should first think whether or not their post will be helpful before hitting publish.

12.5 tweets per second were sent using the promoted hashtags during Hurricane Sandy

When a disaster happens, dedicated hashtags usually appear, which are then promoted by the authorities.

These make it easier for people - including first responders - to keep up to date with the latest developments regarding flooding, power outages and road closures, and where people may need to be rescued.

Using these dedicated hashtags to post non-essential information and platitudes can drown out the updates that really matter.

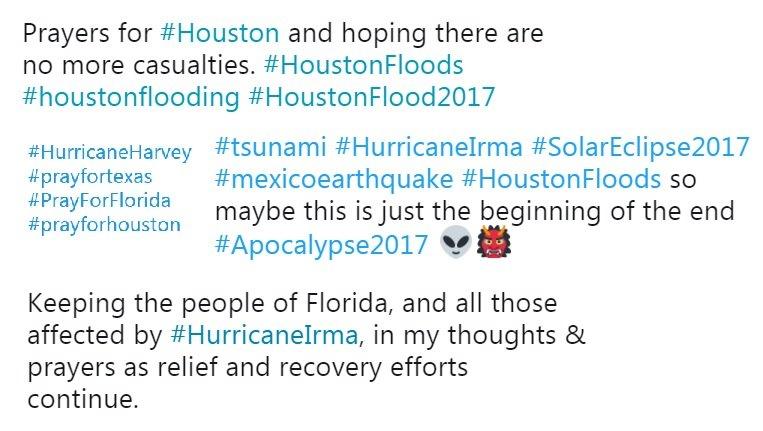

For example, during most natural disasters and terrorist attacks, a #Prayfor hashtag will quickly become popular - take #PrayforHouston or #PrayforBarcelona. Tweets like these often contain key search terms, but offer very little to those in need. It means those looking for help or updates have to trawl through posts that offer very little useful information.

These tweets use hashtags from disasters without offering useful information

Naturally, this leads to frustration from people who are relying on social media to keep up to date with the latest developments:

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Given all of this, how can you know if your update is essential? Kevin Sur, an instructor at the National Disaster Preparedness Training Center at the Ohio Emergency Management Agency, has some suggestions.

"Complaints about the weather and non-trained weather forecast information is non-essential. Ultimately, we cannot control Mother Nature," he said.

"For Hurricane Harvey, we had such a high inundation of the general public posting vague information to various platforms, that call centres had a hard time accruing good information to dispatch crews for rescue," he added.

This swell of unimportant posts during Hurricane Harvey led some emergency services to discourage people from posting requests for help on social media. The US Coast Guard made their position clear, asking people to call emergency numbers instead.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

So what kind of things should people be sharing?

"Life safety information. Without a doubt, life safety information," said Kevin Sur. He suggested one example of a safe update: "Maybe something like 'My neighborhood of XXX is flooded, but we are safe, including our dogs at the local Red Cross shelter'."

This post is specific and lets friends and relatives know you are safe without giving any "non-essential" information, which could make it difficult for the authorities to determine their priorities.

Kevin Sur said that, as well as only posting essential information, it is also important to think about what is safe to share. Following the recent hurricanes, there were reports of looting in Houston, Florida, and across the Caribbean. Unsafe social media use during a disaster can play into the hands of these criminals - so users should be extra careful.

"I would use common sense and not post home addresses. I'd also be wary about posting social security numbers, bank account numbers, and what not. Any kind of personal information should be shared on secured communication channels with securities in place," he said.

Looters caught on camera in Miami

He had three, more general, tips for using social media during a disaster: "Follow trusted sources. Government agencies and NGOs that can provide good, reliable, information. Also, follow the local weather service. Here in the US it's the National Weather Service. Ultimately, the weather dictates all of our actions including our rescue operations."

The point, he said, that is most important is also the most obvious. "Use social media to notify your friends and family that you are okay. Use various platforms, because they may not all be on the same one. Remember, engage with your family and ask if they are okay and what they need."

For those who do need help, social media remains a place where it can be found.

Despite the huge number of non-essential posts, Facebook groups and Reddit threads, some with thousands of members, still offered support and advice throughout the recent storms. As Magan Flores explains: "When I saw there was a need for help, being so far away, it was all that I could do. It was either take action, or cry."

- Published11 September 2017

- Published13 September 2017

- Published31 August 2017

- Published15 September 2017