A year later: Liberals still haunted by Trump win

- Published

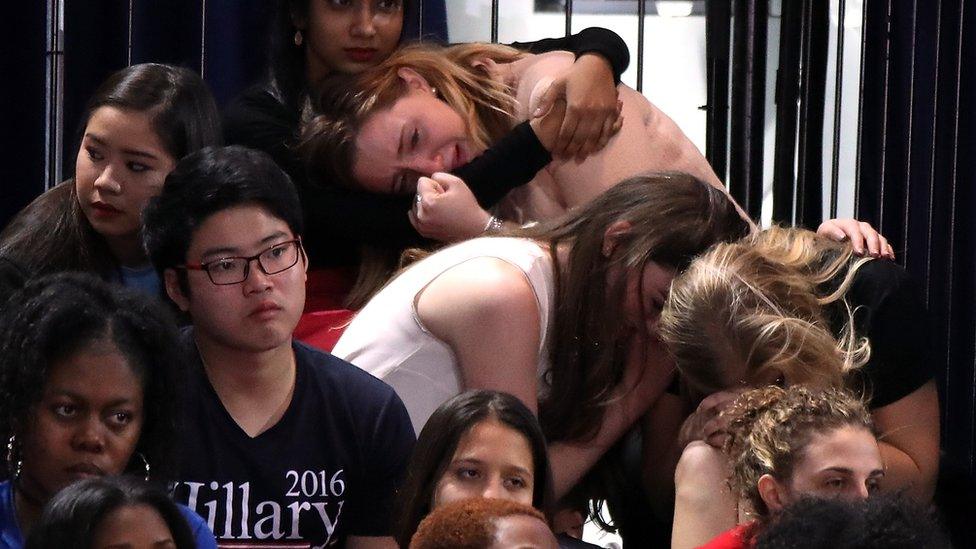

Just over a year ago, the political left in the US watched in shock as what seemed unimaginable happened - Donald Trump won the presidency. Since then, they've mourned, they've marched, and they've moved on. Sort of.

There was a moment on the first full day of the Women's Convention in Detroit, Michigan, last month when the audience came alive.

Linda Sarsour, a co-chair of the event, was moderating a panel about activism in the era of Trump, and glanced down at her phone. She then announced to the cavernous conference hall that there were reports that independent counsel Robert Mueller was about to release his first indictments related to his investigation into possible ties between the Trump presidential campaign and the Russian government.

Thousands of women who had travelled from across the US to attend four days of seminars, speeches and sessions, stood and cheered for nearly half a minute.

For the attendees it seemed a cathartic experience, a glimmer of hope after months of political darkness. But the moment passed, and it was back to considering the slow, steady grind of activism and outreach that continues, nearly a year after Mr Trump's victory left many of them emotionally broken. For a handful of seconds, there was the prospect that, someday, a real victory could be achieved.

"Winning is amazing," Deirdre Schifeling, executive director of Planned Parenthood Action Fund. "Winning kicks ass. Winning is intoxicating. We need to win more and lose less."

A year ago - as Hillary Clinton went down to defeat - winning seemed a long way off. And for many of the women in Detroit, it's been a long road back.

The morning after

As election night 2016 drew to a close, Amanda Litman, who had spent nearly two years on Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign, says she felt physically ill. After she left the Clinton headquarters at the Javits Center in New York, she looked at the people in the street suspiciously.

"I don't know who to trust anymore," she remembers thinking. "I don't know what this country is anymore."

It was a common sentiment among many liberals in the days after the election - a sense of shock, as they faced the prospect of living in Donald Trump's America.

Brandi Collins, senior campaign director for the civil-rights activism group Color of Change, recounts an organisational conference call the day after the election.

"People were crying," she says. "People were angry. People were in shock. And we had 1.3 million members who were looking at us to do something."

Colleen Flanagan, executive director of Disability Action for America, says that Trump's election was "pretty freaking scary". She notes that candidate Trump drew sharp criticism for seemingly mocking a disabled reporter - but he won anyway.

Colleen Flanigan was one of more than 100 protesters arrested on Capitol Hill in September

"No apology, no admission" she says of Mr Trump. "He says disabled people should be put down, and I'm one of those people."

After the election Littman describes being wracked by guilt. As a Clinton campaign worker, she felt like she did all she could - but she also felt a grave sense of responsibility.

"I remember for months, every woman I saw on the street I wanted to apologise to," she says. "Little girls, little boys, I wanted to tell them, I'm so sorry this is the president you're going to grow up with."

In room after room, seminar after seminar, over the course of the four-day convention in Detroit, women recounted their initial reactions to the news of Mr Trump's win. Some initially thought it wouldn't be too bad; that Candidate Trump might morph into a more moderate, restrained President Trump.

Diane Russell, a former Maine legislator now running for governor, says she knew otherwise, having experienced seven years under Maine Governor Paul LePage, who ran as a blunt outsider and boasts that his victory helped foreshadow Mr Trump's.

"It's going to be really bad," she remembers telling her friends. "I don't think you know what's coming. He means what he said."

Days of Reckoning

After the election, liberal fears were confirmed. Mr Trump assembled a conservative administration and continued tweeting and speaking in a confrontational, unvarnished style. At his swearing in ceremony, he gave his "American carnage" inaugural address.

The following day, hundreds of thousands of women across the US took to the streets to protest - organised by the same women who would later put on the Detroit convention.

For Litman, it was a bittersweet moment.

"I wish we had seen this kind of energy six months ago, because then maybe we wouldn't be having this march in the first place," she remembers thinking. "To see people marching on the sisterhood's behalf was really moving … and really sad."

Then - after weeks of "sleeping, drinking, crying and figuring out what to do with my life" - Litman says she decided to fight back. She founded the group Run for Something, which recruits and sponsors millennials to run for local political office.

"I needed something to absorb my grief and my rage and my depression into," she says. "Working is an incredible way not to have to deal with your feelings."

That was a common sentiment among the attendees of the Women's Convention.

"It was really a moment of reckoning for us," says Collins of Color for Change. "We just decided we were going to say to our members that we're all in, that our goal is to make Trump unsuccessful as president and to make this administration unsuccessful."

Initially, her group tried to block the confirmation of the president's cabinet nominees. Most were easily confirmed. Some, like Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, squeaked through.

Athena Soules channels her Trump frustration into political sign-making

"We didn't know what a win would look like in this climate or whether a win was even possible," says Collins.

Then they drew blood, latching on to sexual harassment allegations against conservative Fox News talk show host Bill O'Reilly. After a comprehensive campaign, O'Reilly resigned - their first high-profile scalp, which she says helped build momentum for successful campaigns to force the president's business councils to disband and presaged the wave of sexual harassment awareness that crested with the Harvey Weinstein scandal.

In the months after Mr Trump's inauguration, Flanagan focused her efforts on blocking Republican efforts to repeal Barack Obama's healthcare reforms. She was part of a group of disabled protesters who assembled in the hallways, external of the US Capitol until they were arrested and forcibly removed by police.

"As an activist, it was very, very inspiring," she says of the successful efforts to derail Republican plans. "Our community of activism around disability rights is used to losing. To see that right now Obamacare is not repealed is a win."

Everyone in Detroit had a story of struggle and hopes of success.

Holistic healer/coach Ginny Dodge from Rochester, Michigan, ran a seminar session on "how self-care fuels rebellion" - coaching conference attendees on how to stay mentally balanced when the drumbeat of Trump news makes them scared and angry.

She says much of her private practice post-election has been teaching her clients how to take negative emotions and use them to fuel activity and positive energy.

Athena Soules of Brooklyn paraded around the convention hall carrying a #metoo lighted sign - a reference to the viral sexual harassment awareness campaign. She constructed a collection of light boards that were displayed during a Saturday evening "social justice concert".

"I was inspired, motivated to figure out how I could best use my messaging not only to resist, but to fight back," she says. "I'm able to contribute with my art. It's very empowering."

Ghosts of 2016

Despite the optimism and energy at the Women's Convention, trouble still lurks for the Resist movement - and the Democratic Party as a whole. November 2016 may be a year in the past, but its ghosts still haunt liberals.

"Something happened, and women let it happen," Congresswoman Brenda Lawrence of Michigan said in her convention speech. "We have to do some soul-searching. We can never allow what happened last November to ever happen again."

Ms Lawrence was a late addition to the convention line-up. Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders was originally invited as a keynote speaker at the event but withdrew after sharp criticism from some convention participants.

They had questioned whether a man should have a prominent position at a women's conference and expressed resentment over his contentious primary campaign against Democrat Hillary Clinton.

Less than a week after the convention wrapped up, former Democratic National Committee head Donna Brazile revealed that the Clinton campaign had exercised effective control over the party apparatus months before the Democratic primaries began.

Bernie Sanders, after originally accepting an invite to speak at the Women's Convention, travelled to Puerto Rico instead

This has prompted Sanders supporters, of which there were many at the Women's Convention, to re-air old complaints of a "rigged" Democratic system.

Then there's the concern that the resistance risks being too focused on opposition to Mr Trump, instead of detailing its own agenda and priorities.

"When we talk about reclaiming our time, it's not necessarily about one person or one administration, because if we make it about that, then we are only reclaiming it for a moment," former Ohio state Senator Nina Turner told convention-goers on Friday night.

"The fact that we are women and we can shake and shape the world means for me we are reclaiming our time for history and beyond."

History, however, has a way of biting back. And Litman still says she sometimes wakes thinking the past year has been a bad dream, only to turn on her phone and face the truth.

"I don't think I'll ever get over it," Litman says. "I am now a person who worked for Hillary Clinton and lost the presidential election. Of the thousands of staffers and volunteers around the country, this is just who we are now. And that is sort of a startling thing to realise."

Then, like the thousands of other women who came to Detroit to imagine a day when winning is more than just an applause line, she goes to work.