A Canadian row over rent that goes back 150 years

- Published

The Robinson Huron territory is one of 70 First Nation lands covered by treaties in Canada

Since 1874, thousands of indigenous people in the province of Ontario have been getting just C$4 ($3.15, £2.40) a year for their land. Now they say it is time to raise the rent.

On Treaty Day back in August, people from Nipissing First Nation were queueing to receive C$4 in cash.

Although it may not seem like much, the money is a symbol of the signing of the Robinson Huron Treaty - a landmark agreement between representatives of the Crown and the Ojibway people in 1850 that became a template for how Canada would draft agreements with indigenous people in the decades to come.

In the treaty, the government agreed to give the signatories and their descendents a yearly payment in exchange for sharing the land. This kind of agreement would become a template for future treaties across the country.

Today, there are about 70 treaties in Canada that represent about 500,000 people in 371 First Nations. Some include provisions for a yearly payment of C$4-5.

Treaty Days are generally observed in late summer, depending on the community, and are typically a happy time to celebrate the relationship between indigenous people and the government of Canada, says Gina Starblanket, who teaches indigenous studies at the University of Manitoba.

But as many First Nations continue to argue with the government over housing, education and healthcare, treaty days take on a double-edged meaning.

"Some see it as a reminder of violence and forms of oppression," she says.

At a time when Canada is engaged in a national conversation about reconciliation with indigenous people, some members of the Robinson-Huron Treaty want to raise the annuity for the first time since 1874, when it was raised from C$2 to C$4.

"If it doesn't start there, (reconciliation) is probably going to be a non-starter," says Mike Restoule, chair of the Robinson-Huron Trust.

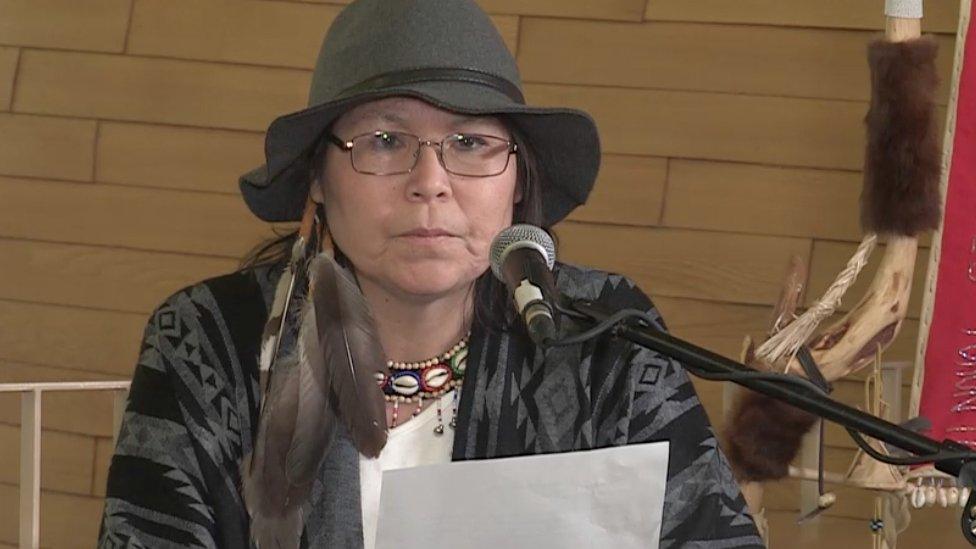

Robinson Huron Treaty plaintiffs gather in Thunder Bay, Ontario

Twenty-one First Nations are taking the province of Ontario and the federal government to court. Testimony began in September and could run until March.

They are joined by two other First Nations representing the Robinson Superior Treaty, who are arguing a separate case at the same time.

Plaintiffs in the Robinson treaties lawsuits are arguing that the original agreement contained an augmentation clause that allowed for the annuities to be increased with the land's value "as her majesty may graciously be pleased to order", and that such an increase is long overdue.

The outcome of either case could set a precedent for how the government treats indigenous land claims in the future, says David Nahwegahbow, one of the lawyers representing the Robinson Huron plaintiffs.

"It has some potential for broader implications, because from the First Nations side, treaties are nation-to-nation," he told the BBC. "Those treaty agreements from time to time need to be renewed."

The Robinson Huron Treaty covers a land area of about 100,000 sq km (39,000 sq miles), stretching north from the shores of Lake Huron up to Lake Superior, and is home to about 30,000 First Nations people.

At the time it was signed, William Benjamin Robinson had one goal - get the rights to the land's natural resources. The Ojibway people, who were not accustomed to written treaties, believed that they were agreeing to share the land, Ms Starblanket says.

"Inherent in indigenous political and legal orders was an understanding of treaties as living, breathing agreements," she says.

But over the next 167 years, the annuity would remain stagnant while the Canadian government reaped the benefit of lands rich in minerals and other natural resources.

A yearly sum that was once the equivalent of about $100 is now barely enough to buy a cup of coffee and a doughnut.

Idle No More protest on Canada's Parliament Hill

Although a value has not been specified, the lawsuit asks the government to make amends for unpaid annuities and set a new yearly rate.

Testimony is currently being heard in courtrooms throughout the region, so that various First Nations may attend.

Historically, indigenous groups have struggled to have their land claims addressed. It was only in 1951 that they could sue the government, Mr Nahwegahbow says, and it was not until the Constitution Act of 1982 that their treaty rights were enshrined in law.

"This is one of those lawsuits that proves why we need to teach more history in this country," says Derek Ground, a lawyer who specialises in indigenous land claims.

Mr Nahwegahbow thinks the Robinson Huron case stands a strong chance, as the Robinson treaties were the only ones to include an augmentation clause, plus the government had previous raised in the annuity once before.

But perhaps what is working most in their favour is the changing political climate.

Since the Truth and Reconciliation Committee's report highlighting the horrors of Canada's residential school system, public favour has turned in favour of reconciliation. Prime Minister Trudeau has made making amends a key tenet of his government's policy.

But both the plaintiffs and the federal and provincial governments have signalled an out-of-court settlement would be ideal.

"Honouring the treaty relationship, based on the recognition of rights, respect, co-operation and partnership, is important to this government and is key to achieving lasting reconciliation," said a spokesperson for Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada.

"The Government of Canada prefers negotiated outcomes whenever possible, and we are currently engaged in discussions on moving this case out of the Court process."

- Published1 November 2017

- Published6 October 2017

- Published29 May 2017