Why I injected myself with an untested gene therapy

- Published

The moment Tristan Roberts became the first human to inject an untested, experimental gene therapy into his stomach fat, he was sitting on a leather couch in his friend-slash-yoga instructor's living room, not on a doctor's examining table.

The glass coffee table in front of him was strewn with syringes. A Chihuahua mix wearing an inflatable recovery collar snored beside him.

The event was livestreamed on Facebook, external, and hundreds tuned in (later, Roberts' mother watched, though she was "not thrilled" with his decision). On Roberts' right was Aaron Traywick, head of Ascendance Biomedical, the nascent company behind the treatment. A network of unnamed researchers around the US assembled the vials in front of them.

"We do not advise that anyone watching this video do what is about to be done here," said Traywick, who is not a scientist and identifies primarily as a "community organiser".

"Tristan Roberts is completely within his rights according to the FDA and the rule of law in this nation… to self-experiment on himself in any way that he deems medically appropriate. It is his body and it is his right."

Roberts - a wiry 28-year-old computer programmer with a mop of dirty blonde hair - also has no formal training in medicine or genetic engineering. That's partly the point. He and Traywick are members of a growing community of biohackers, the do-it-yourself movement in biology, medical science and genetics that has sprung up outside the confines of universities and pharmaceutical firms.

There are now biohacking conferences and community biohacking spaces in Silicon Valley, Boston, New York City and Austin, where high school students, biomedical start-up owners and professional scientists gather to educate and experiment together. Their simplest experiments include making glow-in-the-dark beer; the most lofty aim to cure disease, clean up oil spills, and defeat the aging process.

What Roberts was about to do has been characterised by scientists and bioethicists as everything from "fringe" to "risky" to "frightening". The harshest assessment came from Scott Burris, an expert on HIV public health policy at Temple University.

"This is delusional behaviour," he said. "It's not plausible to me that this guy is even on planet Earth."

But Roberts believed these voices were too cautious, too hemmed in by convention.

"We may be risk takers but we're not stupid," he said. "I think we're heading towards a part of time where patients and test subjects are able to have a greater stake in the outcome of the experiment."

Roberts is not the first person to inject himself with an unregulated gene therapy. At least three individuals have publicly attempted to augment themselves with genes that will inhibit cell death or boost muscle growth, and self-experimentation is also happening in private.

But Roberts is the first person to do so publicly in search of a cure.

Roberts prepares for the injection

Six years ago he was diagnosed as HIV positive. Two years ago, he stopped taking conventional antiretroviral drugs.

His reasons were manifold - he hated the side effects, feared that missing a single dose could build up the virus' immunity. But he also rejects the idea of being on medication for the rest of his life. Roberts wants to be cured.

"I'm excited about the possibility of potentially curing this, maybe for a few months, maybe for a few years - maybe indefinitely," he said. "But there's only one way to find out."

Roberts filled one of the syringes from the vial, lifted his T-shirt, and expelled a breath sharply.

"I want to dedicate this to all the people who have died while not being able to access treatment," he said.

Then he pinched a thin fold of skin on the right side of his bellybutton and inserted the needle.

The tiny amount of liquid Roberts injected into the fat cells under his skin contained trillions of plasmids, hoop-shaped pieces of DNA containing a section that should trigger production of the antibody N6.

A US National Institutes of Health (NIH) study showed N6 neutralised 98% of the HIV virus in lab conditions. The antibody came from a single person, one of the tiny number of HIV patients known to scientists whose bodies somehow manage the virus on their own.

Roberts' hope, and the hope of the treatment's creators at Ascendance, was that the plasmids would successfully cross into the nuclei of Roberts' cells and coax them into producing N6 antibodies. The goal is a "moonshot" - a cure for HIV, and one the biohackers believe they can bring to market faster and more cheaply than institutions hampered by regulations and corporate concerns over profitability.

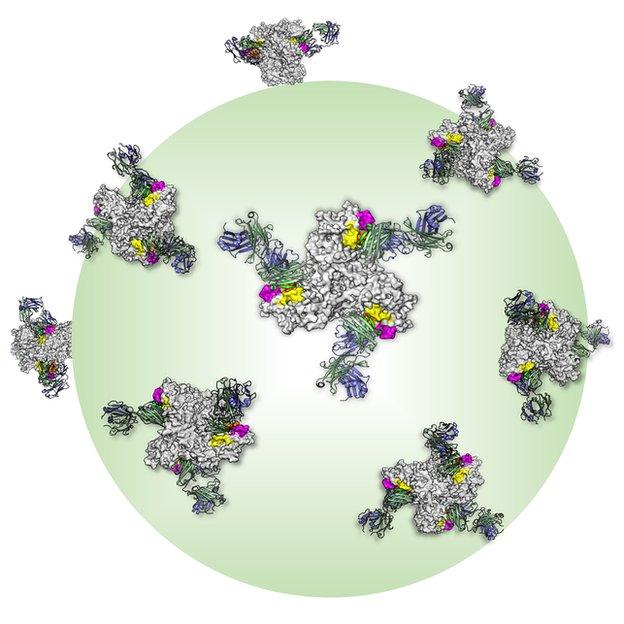

This illustration depicts N6 antibodies (in blue and green) binding to HIV envelope spikes on the surface of the virus

"DNA is a language and I believe people that already live in this generation will learn to be poets of that language," Machiavelli Davis, a friend of Roberts who helped develop the treatment, said on the Facebook Live.

Many scientists and bioethicists argue that experiments like this one are too amateur to produce any meaningful results, that the dangers of self-experimentation outweigh the speculative benefits, or that patients who try self-experimentation may have no idea what they're signing up for.

"I strongly fear that, without a robust structure for conducting risk-assessment and handling risk and liability issues, the Ascendance Biomedical model will only transfer all these heavy, complex responsibilities to individuals at their own cost and peril," wrote Eleonore Pauwels, a science policy expert at the Woodrow Wilson International Center and an expert in genomics.

But now that anyone can obtain a custom gene sequence with the ease and convenience of online shopping, people like Roberts can play in a genetic arena that was once walled off.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can crack down on unlicensed human testing, and the sale of gene-editing products or kits intended for self-experimentation is against the law. But whether or not the act of self-administering an untested drug is illegal is a grey area amateur scientists and biohackers are eagerly taking advantage of.

"We've been living in a medical system that is very paternalistic, where you don't learn what happens in your body. What you see happening now, it's the rise of the new bio-citizen," said Pauwels.

"How do you democratise [medicine] without taking an enormous amount of risk? It's a big question."

Three weeks later, Roberts walked into the chilly offices of a blood testing facility in downtown Washington DC for his second blood test since self-administering the treatment. In a few days, he'd be able to see if the treatment was having any effect on the virus.

A tall lab technician in a papery smock sat Roberts in a padded chair and deftly collected three vials of Roberts' blood in under a minute.

"I'm excited to see the results, but at the same time it's tempered by a bit of non-attachment. It's rare that you get things right on the first shot," said Roberts. "I'm in this for the long haul."

Roberts' friends and family were nervous about his desire to become "patient zero", but knew better than to try to talk him out of it. A few years ago, he left a $75,000-a-year computer programming job after he said the money and the comfortable apartment weren't making him happy.

He has no permanent address, floating between his boyfriend, his family and friends' homes. For his freelance programming work, he insists on being paid only in cryptocurrency, though that presents its own logistical challenges. He nearly couldn't pay for the bloodwork because he was having problems quickly converting his Bitcoins into dollars.

Last year, during a protest through downtown DC, police officers arrested Roberts after they said he spray painted the word "CORRUPT" on FBI headquarters.

"Occupy the city!" he yelled, external just before the officers pushed his head into the car. (He did community service in exchange for a clean record.)

Roberts, left, just after getting his blood drawn, with Aaron Traywick

Despite his appetite for risk, Roberts was feeling uneasy in the three weeks since injecting the plasmid treatment. First, the skin on his back broke out in large red bumps. He figured he was bitten by mosquitoes, but couldn't be sure. Then he was felled for four days by a strange, feverish feeling, a loss of appetite, and gastrointestinal issues.

"I'm fricking terrified it might be the plasmid," he said. "I'm 98% certain this is fine. But there's still this 2% that's like - this could be something terrible."

The nightmare scenario would be that the plasmid was replicating out of control. If he went to the emergency room, could the doctors there be expected to help when they had no understanding of the substance he'd injected?

Then again, he thought, was this a sign that the treatment was actually working?

After a few days, the symptoms subsided, leaving Roberts to wonder what was happening inside him.

By the time he took the blood test, the Facebook Live video of the injection had been viewed more than 20,000 times. Mark Connors, the lead NIH scientist who discovered the N6 antibody, was among the viewers.

Connors was unimpressed with the scientific reasoning behind the treatment.

"These seem like very smart young men and they have command of some of the facts, but not all the facts," he said.

Professor Jennifer Doudna: "Once one understands the sequence of DNA in a cell it's possible to rewrite it."

While N6 is more versatile than any other HIV antibody previously discovered, Connors said it can't wipe out the virus all on its own, and there is a debate raging in the field about whether or not antibodies alone will ever be able to cure the virus. HIV's protein envelope continuously mutates, shifting into forms that prevent our antibodies from binding to and neutralising it. As potent as N6 is, HIV can still develop a resistance to it, making it a poor candidate as a "monotherapy" or stand-alone treatment, said Connors.

"For the most part, the rules aren't what take so long [in drug development]," he added. "It's not the FDA sitting on drugs. The reality is this is a deliberative process."

Another thing that concerned scientists about Ascendance was the lack of detailed information on the company's website - there's no phone number, nor a list of employees or advisors. Traywick said this is in part due to proprietary reasons and in part because the company is still so young. But he also said he needs to obscure the identities of the working scientists who are biohacking for Ascendance on the side, to avoid opening them up to legal or reputational risk.

Traywick put the BBC in touch with the researcher who assembled Roberts' treatment by phone, though he refused to give his name or location in the US. He codenamed him "M McConaughey" - a reference to actor Matthew McConaughey's portrayal of the 1980s amateur HIV researcher in the film The Dallas Buyers Club.

In a call, "McConaughey" actually disagreed with Traywick and Roberts' decision to livestream the first injection, and with throwing the word "cure" around. He agreed with Connors that this first dose is unlikely to have an impact, and worried that the livestream set up unrealistic expectations.

"Even when you're doing everything you can to make things quick, you can't be nature," he said. "Biology is very slow and difficult."

Among the tiny handful of biohackers and researchers who have publicly self-experimented with gene therapy, there is disagreement over whose science is sound. Josiah Zayner, chief executive of a company that sells do-it-yourself gene-engineering kits, has injected himself with gene therapies in front of live audiences, but he refused to comment on Ascendance or Roberts, writing that they have "very little idea what they are doing".

Hassan has been given a new genetically modified skin that covers 80% of his body

Brian Hanley, a microbiologist who gave himself a gene therapy designed to increase his stamina and life span, hates being called a biohacker. While he sees little problem with scientists experimenting on themselves, he fears that biohackers who promote self-experimentation will encourage total amateurs to take risks they don't understand.

"[They] could give themselves a significant issue, potentially including dying from it," said Hanley. "The biggest danger is you could infect yourself with something."

George Church, a pioneer in genome sequencing who has become a de facto sounding board for people interested in self-experimentation, said that while he always recommends caution, clinical trials and the involvement of physicians, sometimes startling results can come from a single patient. He pointed to the example of Barry Marshall, a physician who in the mid-1980s proved that ulcers are caused by bacteria - by drinking an infectious broth.

"It was dramatic enough that it led to his Nobel prize," said Church. "Anything is possible."

On yet another friend's couch in a tidy townhouse in Arlington, Virginia, Roberts prepared to go on Facebook Live again to share the results of his blood tests. He had purposefully not looked at the data yet.

The room was full of people. A film crew for a forthcoming documentary series on biotech prepared to capture his reaction. Aaron Traywick watched from the kitchen, and three of Roberts' friends whispered in the background.

"My greatest fear of turning out to be Geraldo Rivera is popping up," Roberts said. "He goes to reveal what's inside Al Capone's vault and it's just some trash, some empty beer bottles."

Without the means to test for the presence of N6 in Roberts' blood, they were relying on his viral load count. The day before injecting the treatment, his blood contained 11,912 copies of the virus per millilitre. He hoped to see that the viral load dropped to 2,000 copies or less. If it was in the 2,000 to 8,000 range, conclusions would be hard to draw. A flat or increased viral load could indicate the treatment had failed.

Roberts and his friends share a drink after learning his test results

Although Roberts enthused about a patient-controlled future when the democratisation of medicine has toppled big pharma, this was obviously also personal. He admitted to fantasising about telling his parents over Thanksgiving dinner that the treatment had worked.

He also recalled getting a paper cut soon after he first found out he was HIV positive. Looking down at his hand, he saw his own blood as a poison.

"That's what I'm looking forward most to helping heal," he said. "It's not necessarily the infection itself, but the possibility of harming others."

After greeting the audience on Facebook Live (which again included his mother), Roberts told them: "I think it's time."

He opened the documents sent from the lab and frowned slightly as he read. Then he laughed.

"Alright, so - yeah, this was not what we were hoping for."

According to the test results, Roberts' viral load rose from 28,800 on week two to 36,401 on week three - still low levels, but not the desired results. His count of CD4 helper T-cells - the immune system cell that HIV attacks - was higher than he'd ever seen it, but there was no way to know what that meant.

"More data is necessary," Traywick chimed in from off-camera. Then he sat down next to Roberts, joking: "We didn't kill you."

After they switched off the broadcast, Traywick slumped backwards in his seat. One of Roberts' friends quietly slipped the magnum of sparkling wine that had been sitting on the kitchen counter into the refrigerator. They opened a bottle of red instead.

Traywick said that this is part of his vision for the company - one that shares its failures publicly just as readily as its successes.

"I am a little bit let down," said Roberts, sipping from his glass. "It's hard."

Despite the initial failure, Roberts said he believes that the gene therapies that he and others are testing will hold the key to obliterating HIV, as well as other diseases that have stumped the medical field.

"It's opened up so many possibilities, it's redefining what it means to be human."

In December, Ascendance's researchers will release a second version that contains 10 to 100 times the number of plasmids; Roberts plans to inject that as well. He has no plans to return to medication and said he fully expects to be cured someday.

Connors, the NIH researcher, tuned in to Facebook to watch Roberts get his results. He disagreed with the biohackers' belief that traditional research methods move too slowly - human trials of N6 injections are set to being in early 2018 - and he said that he wished Roberts would go back on anti-virals.

"It kind of breaks my heart," he said.

But, he added, Roberts actually has something in common with the patients whose bodies naturally create antibodies like N6 and others currently being studied as a means to combat the virus.

"The people who make up the cohort are people who refuse treatment," he said. "They have a similar independent streak."