Ex-Muslims: They left Islam and now tour the US to talk about it

- Published

Muslims who leave the faith often face abuse and violence - but a grassroots group that's touring American colleges is trying to help.

Ten years ago, Muhammad Syed became an ex-Muslim.

Born in the US, he grew up in Pakistan believing "100 per cent" in Islam.

"You don't encounter doubt," he says. "Everyone around you believes it."

And then, in 2007, he realised something. He didn't believe at all.

As a boy, Muhammad was interested in "astronomy, the space programme, Star Trek, Star Wars".

He calls himself liberal. His parents had PhDs.

He moved back to the US in his early 20s, a few months before 9/11. When America went to war, he joined anti-war protests.

At the same time, some of his Pakistani friends became "ultra conservative".

"There was one guy in particular," says Muhammad. "I knew him through high school.

"We were in the same college. We were similar people - he was liberal like me. Then he grew this foot-and-a-half long beard."

His friend's outlook "scared" Muhammad.

"He was talking about torture in the grave (an Islamic belief in punishment after death)," he says.

"And he was talking about it being a real thing that people have witnessed - a very superstitious type of thinking.

"Coming from a scientific background [and] going into that, was a little bizarre. So I spent about a year or so looking into religion."

Muhammad studied the Koran, the hadiths (reports describing the Prophet Muhammad), and secondary texts.

"My perspective was 'Islam is humanistic and scientific' - the sort of thing you're told," he says.

"I wanted to show my friend his perspective was wrong. But when I went through it, it was very clear that his perspective was actually the Islamic perspective.

"He was right and I was wrong."

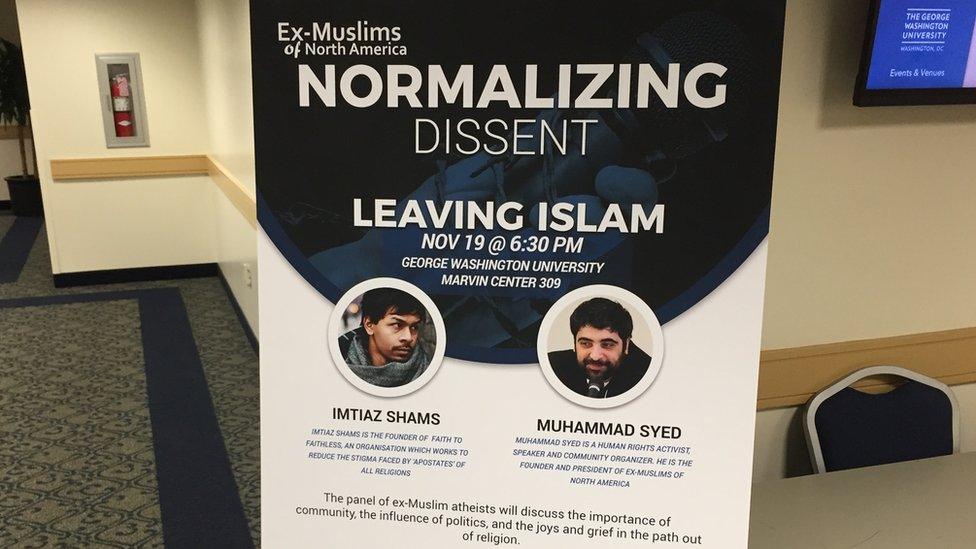

Imtiaz Shams and Muhammad Syed speaking in Washington DC

In the same period, Muhammad had dinner with friends. One had survived leukaemia earlier in his life.

"He was praising God for his recovery," says Muhammad.

"But in my head I was thinking about the probability of recovering from leukaemia - there's a certain percentage that do.

"I thought: 'How do you know that God is the one that saved you - versus you being in the percentage that is saved generally?'

"At that point I knew what he is saying is fantastical. It's not really real. It's an issue of probability.

"From there I thought: 'I understand this is all false, and I've understood it for a while, I just haven't self-acknowledged it.'"

Did he chose not to believe?

"It's not that you want to, or don't want to, believe it anymore," he says.

"It's like you understand Newton's equations for gravity - if you understand them, you understand them.

"You can't not understand them afterwards."

Muhammad calls his family "relatively liberal". "Mom in particular was very open-minded," he says.

So he decided to tell them he was an ex-Muslim. Not immediately, but "within a few weeks, certainly a month or two".

And what did they say? "They were obviously traumatised and shocked," he says.

For some Muslims, leaving the faith is a religious crime. A 2016 report found atheists can - in principle - be sentenced to death in 13 Muslim-majority countries, external.

"If you love somebody you want the best for them," says Muhammad.

"If you believe that by going down a certain path a relative will - say - burn for eternity, it's hard not to push back.

"A lot of that pushback comes from a place of love. It's not from a place of hate."

Sarah Haider says she is an "accidental campaigner"

After realising he didn't believe, Muhammad was open about it. He spoke to friends about his beliefs. He got to know other ex-Muslims.

At one social event, he met Sarah Haider. Born in Pakistan and raised in Texas, Sarah left the faith when she was "15 or 16".

She had never met another ex-Muslim.

"When I found out Muhammad was an atheist, I didn't believe him," she says.

"I thought maybe it was a joke. When I realised it was the case, it really was astounding to me."

Sarah describes her parents as "conservative relative to Western parents in general, and liberal relative to Muslim parents".

"They never abused me," she says. "But they were never happy with my choices. I got pushback every step of the way.

"It was a long process for them to understand this was an intellectual choice, and to have some mild respect for it. But they did get there, and many ex-Muslims' parents would not have.

"I know ex-Muslims who have no contact with their family at all - either for fear of physical abuse or retribution, or because the family have shunned them."

After meeting each other, Muhammad and Sarah decided to find other ex-Muslims.

"Sarah thought she was the only one," says Muhammad. "We thought there were probably others like that."

Through word-of-mouth, and online forums, they built a small, informal network of ex-Muslims. Then came the next step: meeting in real life.

Muhammad tried to vet people. He spoke to them on the phone. But, despite the precautions, they feared violent Muslims discovering their meeting place.

"It was pretty scary," remembers Sarah.

"I was tense from the very beginning. In fact, I was not entirely on board with the idea.

"I was curious and excited, but part of me was nervous. I knew I was taking a risk just showing up."

Muhammad remembers "one guy going to the bathroom for a really long time".

"I was half-joking to Sarah that he's probably assembling a gun," he says.

Half-joking but half-thinking…?

"Could be," he says. "Could be."

What it's like coming out as an ex-Muslim

The guy came back from bathroom without a gun. The meeting went well, and word spread.

Other events took place in bars, cafes, and restaurants in the Washington DC area. One person travelled six hours there and six hours back.

Some people were "badly traumatised". At almost every event, someone cried.

"When we saw the demand, we thought we needed to do more," says Muhammad.

They decided to expand to other cities. In autumn 2013, he and Sarah created Ex-Muslims of North America, and became the public face of apostasy.

Did he think twice?

"Of course," he says. "You have to assess the risk. You have to figure out whether this was worth it.

"But there was no other way. Somebody had to take that chance. Somebody had to make that happen."

But why Muhammad? He could have done nothing, and had an easier life.

"I didn't honestly see another way," he says.

"There were no other people that were doing this, even around the world. We were in the right place, the right time, and I had the right mentality.

"I would say it's part of my upbringing. If somebody is in trouble you try to help."

Four years on, Muhammad and Sarah's network - which is run by volunteers and relies on donations - has around 1,000 ex-Muslims in 25 cities in North America.

People often call in the middle of night. Sometimes they're suicidal.

One person - after telling his family he was leaving Islam - had a gun put to his head. Another was forced to take part in an exorcism.

Another man, fearing for his safety, fled his family. They hired a private investigator to find him; he has moved states six times in 18 months.

Ex-Muslims of North America (Ex-MNA) help in different ways.

"If they want to talk, we usually connect them with somebody - similar age group, somebody that can understand them," says Muhammad.

"Often it's ethnic - so, for example, Saudi people can understand Saudis better. We have people from 40 different ethnic backgrounds."

The group offers practical help, too. "We had a young girl, her parents weren't letting her study," says Muhammad.

"Home schooled at high school, expected she would get married, she can't go to college, she wanted out. She wanted to live her life.

"We were able to connect her to someone else, someone who had a spare couch. It's not much - but for somebody who has nothing, it's huge."

Do they get threats, as well as cries for help?

"Usually via email or social media platforms," replies Muhammad.

"But there's a random person saying something on the internet, and then there are very specific, credible threats. Some people prove they are a legitimate threat.

"The first time it happened we called the police. They didn't understand the issue at all. But we were able to connect with the FBI and they understood it."

Has Muhammad ever left his home because of a threat, even for one night?

"We talked about doing that," he says. "We decided not to."

On a Sunday night in Washington DC, a policeman sits by the door of room 309 at George Washington University's Marvin Center.

Inside, around 50 people - men and women, young and old, a mixture of races - wait patiently. They are here for "Normalizing Dissent", the Ex-MNA's tour of college campuses.

The tour began at the University of Colorado Boulder (where all bags were searched for weapons) and has taken in Virginia, two dates in Georgia, and DC.

It moves to Boston on Thursday, and there are more events planned next spring. It's a brave move, but Muhammad says the events have been "amazing".

There was an argument in Georgia, but only between two members of the audience.

In DC, Muhammad is joined by Imtiaz Shams, an ex-Muslim from London (Sarah is in Australia). Imtiaz co-founded Faith to Faithless, external, a British group that helps ex-religious people from all backgrounds.

He is younger than Muhammad and similarly well-read. But he has the timing - and confidence - of a stand-up comic.

The talk zips from Islamic scripture, to racism - they get called "white" a lot - to the problems with right and left-wingers.

Parts of the right use ex-Muslims to demonise brown people, Muhammad and Imtiaz say. At the same time, parts of the left white-wash Islam's faults so they "don't upset a minority".

"For a decade I was an Islamic extremist... now I want to counter that ideology"

While Muhammad criticises Islam - "When people talk about how feminist (the Prophet) Muhammad was, they should be ridiculed, they should be laughed at" - he praises parts of it.

"You can find beauty within Islam itself," he tells the audience. "It's an amalgam of many, many ideas. Some are good, some bad.

"A lot of them are outdated, because it was the 7th Century. It doesn't mean they're all bad. Personally speaking, one of the better things in Islam is the emphasis on charity."

The talk ends with questions - some from Muslims, some from non-Muslims. They are all respectful. The policeman sits by the door, legs crossed, interested.

Before the talk, Muhammad admitted he had doubts. Not about leaving Islam - but about whether being a well-known ex-Muslim was worth it.

"Of course, everybody has those moments," he says. "It's normal, it's human. Is this worth the toll it's taking on me?

"But on the flip side you also see the good you're doing. You see the people who were suffering in bad situations [who are] doing great now.

"It's heartening to hear those stories - to hear how we've affected their lives."

- Published28 September 2015