The cops and politicians joining Canada's cannabis business

- Published

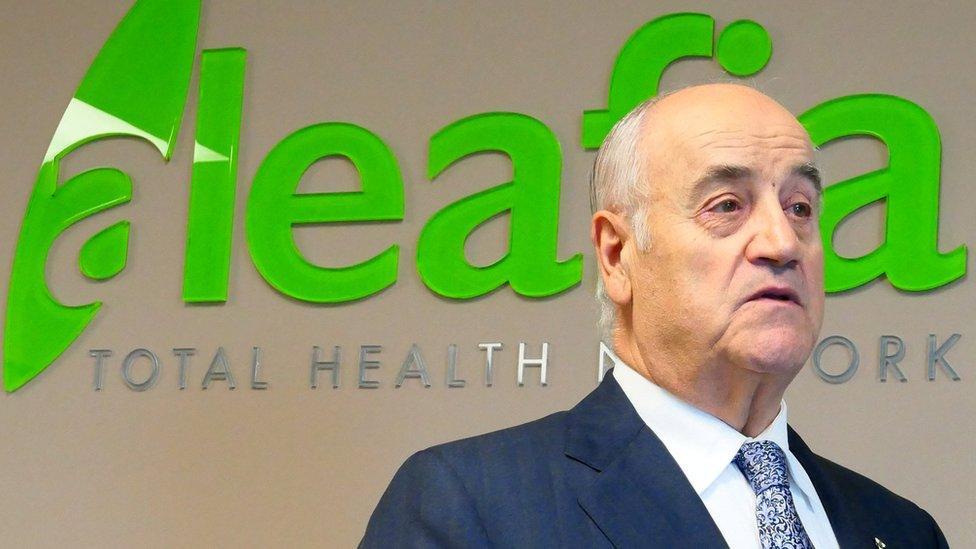

Former police chief Julian Fantino has been criticised for entering into the cannabis business

As Canada moves towards legalising recreational cannabis, there's a surprising group of entrepreneurs jumping into the market: cops and politicians.

In 2015, former Toronto police chief Julian Fantino was "completely opposed" to marijuana legalisation and supported mandatory jail time for minor cannabis offences.

Mr Fantino, who was also a Cabinet minister in the former Conservative government, criticised the now governing-Liberals' plan to legalise the drug, saying it would make smoking marijuana "a normal, everyday activity for Canadians".

In November, along with former RCMP deputy commissioner Raf Souccar, he opened Aleafia, a "health network" that helps patients access medical cannabis.

He also had a change of heart on legalisation, telling the Toronto Star newspaper he now supports, external it as long as it keeps pot away from children and criminals.

In an interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, external, he said his 2015 comments were made "in a different era".

Mr Fantino said his turning point on medical marijuana came when he was minister of veterans affairs and met ex-soldiers who relied on it.

Marijuana activists who have fought against prohibition for decades - and sometimes faced subsequent criminal charges for their activities - were angry over Mr Fantino's reversal on pot.

Prominent cannabis advocate Dana Larsen called Mr Fantino's decision to enter the market "shameful" and "unacceptable".

Meet the former police chief helping to legalise marijuana in Canada

"I would not buy from those people," he says, adding he would tell other marijuana users to do the same.

There is also concern the pot counterculture that flourished for decades will be elbowed out of a likely multi-billion dollar industry by a new corporate sector.

Mr Fantino is arguably among the more controversial entrepreneurs to join the "green rush".

But a number of high-profile former police officers and politicians have jumped into the industry in recent years, including Mr Fantino's Aleafia colleague and fellow ex-MP Gary Goodyear, former Ontario premier Ernie Eves and former deputy Toronto police chief Kim Derry.

Medical cannabis has been legal in Canada since 2001.

Canada was an early adopter of medical marijuana

The industry got a boost in 2013 when federal government regulations shifted to allow licensed commercial producers to grow, package and distribute medicinal cannabis to patients.

Registered patients have also skyrocketed from 24,000 in June 2015 to more than 200,000 in June 2017.

Many of companies supplying that market have plans to expand into the recreational product when the product is legal next summer.

In December, the federal statistics agency estimated Canadians consumed an estimated C$5bn ($3.8bn; £2.9bn) to C$6.2bn worth of marijuana in 2015. Canadians spend about C$7bn a year on wine.

The government is pitching the legislation winding its way through Parliament as a way to keep pot out of the hands of minors and to undercut organised crime.

Derek Ogden spent more than 25 years with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, including as head of the force's drug squad.

He understands the frustration of activist watching the people they battled for decades now entering the industry.

Employees inspect plants at the Emblem production facility in Paris, Ontario

"There's absolutely no way Canada would be in this position right now as far as taking steps to legalise had it not been for the work that the activists did," he says.

But Mr Ogden, who now runs National Access Cannabis, a consultancy that helps patients access medical marijuana, says it's no surprise that ex-cops are in demand.

Licensed producers are hungry for people with security experience who can get clearances and who understand Canadian drug laws.

"One of the ideal groups of candidates to slide into those positions were former law enforcement personnel," he says.

The future of cannabis retail: Seedy head shops could soon be a thing of the past

Mr Ogden himself got into the business around 2014, when Canadian and American producers hired him to consult on security protocols.

His nascent consulting company was "overwhelmed" by the demand.

Mr Ogden no longer believes that people who use medicinal cannabis are simply doing so "to avoid the legal implications" of using the drug recreationally.

He had an "aha moment" after meeting a respected physician who relied on cannabis during a bout with cancer. Mr Ogden now uses it himself for a chronic health issue.

He concedes changing his mind on its recreational use was "a tougher one".

Former British Columbia municipal politician Barinder Rasode "grew up thinking [pot] was a gateway drug that ruined people's lives".

Now she's president of the new National Institute for Cannabis Health and Education, which researches cannabis production and its use in Canada.

Marijuana activists have done "an amazing job" at highlighting problems with prohibition but with legalisation on the horizon, "having many voices at the table is really, really important", she says.

"I don't think the fact that somebody at some point had a different opinion about cannabis should exclude them," she adds.

"I actually think their voices are extremely valuable."

Marijuana is the most commonly used illegal drug in Canada. Almost 60% of drug offences in the country in 2016 were cannabis-related.

Mr Larsen says he doesn't "want to put narcs in jail". But he believes police and politicians who supported prohibition and are now entering the cannabis business should admit they were wrong.

"I want people who were victimised by cannabis prohibition - who went to jail, who had their families torn apart, who lost their children, who couldn't access medical cannabis - I want their voices to be heard," he said.

- Published13 April 2017

- Published27 March 2017