A woman's choice - sexual favours or lose her home

- Published

Khristen Sellers: "I was trying to fix my life. And this put a halt on it."

Across the US, sexual harassment at the hands of landlords, property managers and others in the housing industry can drive poor women and their children into homelessness. It is a problem badly understood and virtually unstudied.

Khristen Sellers needed a home.

The previous few years had been a struggle. She'd left an abusive relationship, been arrested, wandered out and then back into her children's lives. Just as she seemed to be getting back on track, a probation violation sent Sellers to prison for the first time.

After five months, she returned to her hometown of Laurinburg, North Carolina. She was broke and homeless, starting over at the age of 29. She slept on couches. She got a job at a supermarket, then another at a fast-food restaurant.

"I'm walking to these jobs trying to, you know, stay afloat," she recalls.

So when Four-County Community Services - a local housing agency - offered her an opportunity to move into a white panelled, three-bedroom trailer home on the outskirts of town, she readily accepted. That's when the trouble started.

"I was trying to fix my life," she says, "and this put a halt on it."

She had applied for the federally subsidised Housing Choice Voucher Program, better known by its former title, Section 8. In the US, 2.1 million low-income households rent from private landlords using the vouchers, and their rent is partially or fully covered by funds from the federal government.

Laurinburg is located in one of the most economically depressed counties in North Carolina. Vouchers are coveted, and some people languished on the waiting list for as long as 10 years. Four-County was the local agency entrusted with disbursing them.

Based on need, Sellers qualified relatively quickly. Another Section 8 tenant had abandoned the double-wide trailer on Dorset Drive, and Sellers was told that if she cleaned it, she could move right in.

Every morning, Sellers' mother dropped her off alone at the property. For a week, she hauled out broken furniture, pulled rotten food from the refrigerator, scrubbed dog excrement off the carpets and poisoned the cockroaches. There was extensive damage to the property that Sellers couldn't fix herself, but before the landlord would make the repairs, an inspector from Four-County had to take a look.

Sellers remembers the first time the agency's inspector, a former North Carolina state police officer named Eric Pender, came to the property with a clipboard in hand. As she continued to clean, she says the conversation quickly turned from the house to Sellers' personal life.

"'Where's your boyfriend?' 'Why you don't have a man here cleaning?'" Sellers says he asked her. "And I'm like, 'I don't have time for a man, I just came out of prison, I'm trying to get my life right.'"

Undeterred, Sellers says Pender asked her if she "gives head" or if she'd ever been paid for sex, implying that his signature on the inspection was the only thing standing between her and a place to live. At one point, she says he called her into the bathroom under the pretence of showing her a needed repair. She says he pulled her in by her hips, blocked the doorway and took out his penis. She managed to push him out of the way.

Sellers was horrified. And she says it was the first in a string of incidents.

"It was continuous," she says. "He would never sign. Each time he came, it was like, 'You owe me before I sign this paper. And you gotta make a decision.'"

She worried she would lose her voucher if she complained to the housing agency. She tried to hire a lawyer who told her to come back when she had witnesses. A private investigator told her she couldn't afford him.

A colleague she confided in thought she was doing Sellers a favour by going to Pender's boss.

The house Khristen Sellers was offered by Four-County

But the boss told Pender, who confronted Sellers as she was raking the backyard of Dorset Drive. She managed to secretly record the conversation on her mobile phone.

On the recording, Pender said he heard Sellers was "getting tired of me asking you for pussy".

"Be careful who you talk to," he said. "You're on this programme because you need it and you done waited a long time. But it's so easy to lose it."

Just before the recording ends, he added, "We straight - well, we almost straight. You'll take care of me later on."

Sellers says there were moments when she considered giving in. After all, he was a respected local official, a former cop. She was a homeless single mother with a criminal record.

"If I go tell somebody he said that, he'll say 'No, I didn't.' Who gonna look like the liar?" she says. "I just didn't know what to do at that point and I needed somewhere to stay."

Standing in a pile of dead leaves in the backyard of Dorset Drive, Sellers felt utterly alone. What she didn't know at the time was she was just one of dozens of women who had gone through something similar.

In a post-Harvey Weinstein and #MeToo world, most people are well aware sexual harassment occurs in the workplace. But across the US, women are subjected to it in a far more intimate setting - their homes.

Every year, hundreds of state and federal civil lawsuits are filed against landlords, property owners, building superintendents and maintenance workers alleging persistent, pervasive sexual harassment and misconduct, covering everything from sexual remarks to rape. This includes so-called "quid pro quo" sexual harassment, wherein the perpetrator demands sex in exchange for rent or repairs.

"In employment, you leave. It's horrible, but you can leave and go home," says Kelly Clarke, a supervising lawyer at the Fair Housing Project of Legal Aid of North Carolina. "This is somebody who can invade your home."

Martisha Coleman, a young mother who brought a case against her landlord in East St Louis, Illinois, says after repeatedly rebuffing advances, she became so scared of him that she started pushing her bed against the door at night. She says he retaliated when she wasn't home. (The case is awaiting a judge's ruling.)

"He unlocked my door, came inside my house, looked through my items and left a five-day eviction [notice] on my bed."

Situations like Coleman's are virtually unstudied. There has never been a comprehensive national survey of tenants to track the frequency of sexual harassment in housing, or to determine where or to whom it occurs most often. Most advocates and experts believe poor women and women of colour are disproportionately affected, though that is based mainly on experiential evidence and a single, 30-year-old study. Advocates say victims who are undocumented or who do not speak English are also easy targets, as are women fleeing domestic violence.

The lack of affordable housing stock in major American cities compounds the desperate circumstances renters can find themselves in. A single eviction can preclude victims from huge swathes of the public and private housing market.

"The link is vulnerability and poverty," says Kate Sablosky Elengold, a clinical associate law professor at University of North Carolina who prosecuted sexual harassment cases for the justice department's civil rights division. "The risk to a woman standing up against it is homelessness."

Judy tried to put what happened in Laurinburg behind her.

After all, she'd already lost the tiny red house with the blue shutters on the east side of town, and was forced to move back home to Baltimore, Maryland, crammed into a single apartment with her adult children. Besides that, she was ashamed. (Judy requested the BBC not publish her full name).

But then a cousin called to tell her about a story in the local Laurinburg newspaper - Eric Pender and his boss John Wesley at Four-County Community Services were in big trouble. Three women were accusing the men of years of sexual misconduct at the housing agency. Judy pulled up the story, and Googled Craig Hensel, the young lawyer who had finally heard Khristen Sellers' story and agreed to file a lawsuit. Pender was also criminally charged with simple assault.

"I gave [Hensel] a call," Judy says. "I told him something similar happened to me."

Around 2008, Judy moved to Laurinburg and received a housing voucher from Four-County. She was looking for a change of pace - a country lifestyle, far away from big city problems.

Four years later, she says she made a crucial mistake - she signed on a lease for a public housing unit in Baltimore for her daughter. Receiving federal housing benefits in two places constitutes fraud. A caseworker at Four-County Community Services informed Judy the voucher for the little red house would be terminated.

The former offices of Four-County Community Services in Laurinburg, North Carolina

Judy left that meeting distraught, and says that's when she bumped into Pender. She says he offered his help.

Pender had always had something to say about her looks, her shape, the smell of the oil she wore, Judy says. Twice, she claims, he groped her buttocks. This time, she alleges, he told her he could help with her voucher situation if, "one hand washes the other. You help me out, I'll help you out." Judy says it was clear to her that he was talking about sex.

"I felt like my back was up against the wall," she recalls. "I needed to keep a roof over me and my son's heads. I didn't have the money."

According to Judy, Pender came to her home after hours for a single sexual encounter. She assumed Pender would be able to do something to save the voucher. Instead, she says, he did nothing and the voucher was terminated.

"This man used me," she says. "I felt humiliated."

These two women both say they were assaulted by Four-County employees. They did not want their faces shown

One of the last times she saw Pender, Judy made two secret recordings on her cell phone. In the recording, he made comments about her coming to his home, and referenced oral sex. She says she thought she could play it to Pender's girlfriend to get back at him, but never did.

"I didn't try to tell nobody," she says. "Who wants to be publicly known for sleeping with people [for something]? That's like being a whore or a prostitute. That's how I felt."

But months after her move back to Baltimore, she read that not only were three other women claiming sexual harassment, one had also acquiesced to the sexual demands "out of fear" her benefits would be negatively impacted if she refused.

"I can point a finger now because I got three more pointing back at him."

Even if a sexual harassment complaint eventually reaches the proper authorities, the act of reporting can lead to an eviction. That's what Tonya Robinson says happened to her, after she was assaulted by a property manager at an apartment complex in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Twenty-six women later came forward with similar allegations.

"When he touched me, I ran down and told the neighbour who'd been living there for years," she says. "I was kicked out of the apartment, my children and I during the winter time."

Victims can report sexual harassment to state and municipal civil rights entities, private fair housing agencies - like local legal aid offices - and to federal agencies like the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

But the process varies from state to state and agencies often have different requirements in terms of time an investigation can take and level of confidentiality. Civil legal proceedings can take years, and evictions only a matter of weeks.

Besides, many victims are simply unaware they can make a formal complaint. Shanna Smith, president of the National Fair Housing Alliance, says women often tell her, "I didn't know I could do something about it."

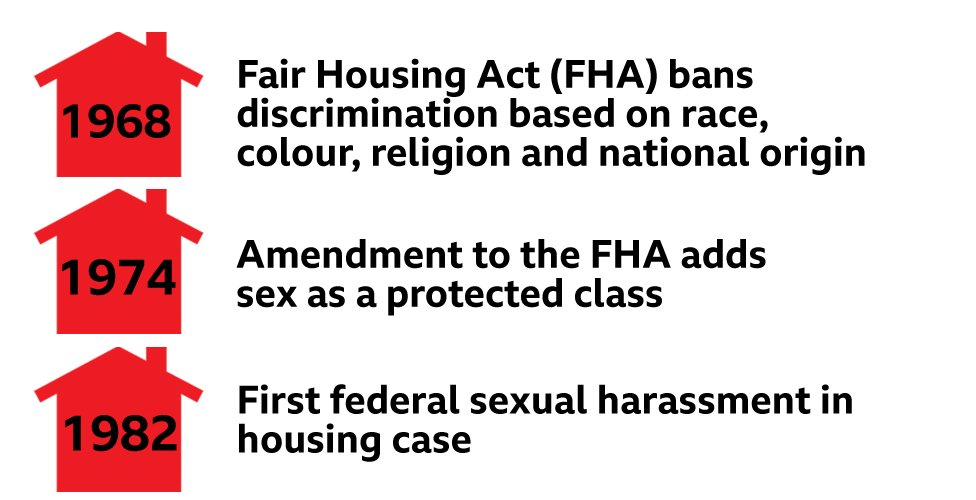

Housing harassment history

In October 2017, the justice department announced a new Sexual Harassment in Housing Initiative which aims to lower barriers to reporting. They opened a dedicated hotline for sexual harassment in housing complaints. New interventions and trainings are being proposed for local police departments and landlord-tenant courts. A nationwide roll-out of these solutions could come later this year.

"Sexual harassment in housing is illegal and unacceptable. Too many women today are being taken advantage of by their landlords," Associate Attorney General Rachel Brand said in a statement to the BBC. "The justice department has made helping these women a priority."

But successfully making a complaint is just the first step. For Khristen Sellers and the other women, it was just the beginning of the ordeal.

"The breadth of it was so shocking," says Jessica Clarke, a former DOJ lawyer who eventually handled the Laurinburg case. "When the person who has the keys to your door, who controls where you live is a predator, there's nothing scarier."

Although Sellers and her lawyer now had other women like Judy willing to go public with their stories, it became clear it was going to be a difficult road forward.

Not only did Pender continue in his job as usual, but one of the complainants was called to Four-County's offices and suddenly recanted. Less than a month later, the woman received a housing voucher.

Four-County also attempted to terminate Sellers' voucher, purportedly over the shoddy condition of the trailer on Dorset Drive. Termination letters sent to Sellers were signed by Pender himself. Her lawyers, which now included Kelly Clarke from Legal Aid of North Carolina, petitioned for restraining orders against Pender and the agency.

"This is clear-cut retaliation," Clarke told the local press at the time. "They're targeting Khristen to scare the other women into keeping quiet."

But by then, the floodgates were open. Women were coming forward with allegations spanning years, and many pointed to Pender's boss, John Wesley.

Samantha Oxendine alleges that in 2010, she brought her newborn son with her to Wesley's office to inquire about a voucher. She claims he told her she could have a voucher that day if she agreed to "come over here and suck it". Oxendine picked up her son and fled. She told her mother Jill, who went back to Four-County's office to complain.

Samantha Oxendine, right, and her mother Jill

"I told them my young 'un didn't have to drop to her knees for nothing," recalls Jill. "I was ready to kill them."

Around the same time, Jennifer Dial was hoping to move out of a dangerous apartment complex into a house she could only afford if she had a voucher. She says Wesley repeatedly asked her to dance for him, or show him her underwear in exchange for one. She never went back and sent the agency a letter of complaint.

"I had to have somewhere for my kids to stay, and all you're worried about is seeing what kind of underwear I have on," says Dial. "It was disrespectful."

Neither Oxendine nor Dial ever heard back, and never received vouchers. Oxendine and her children continued to live with family. Dial gave up on the dream of the house and moved to an apartment only to find it was infested with bed bugs. She lost all her belongings.

Jennifer Dial

Latina Covington knew she could complain to HUD, the government's housing department. She called and told them that Wesley was pressuring her for sex in exchange for a voucher for her disabled brother. On one occasion she alleges he slipped his hand into her pants as they were standing talking. She says HUD referred her to a local housing nonprofit.

But for some reason the nonprofit never returned her calls and her brother stayed on the waiting list for seven years.

"I felt like nobody was hearing me," she says. "Emotionally it really broke me down."

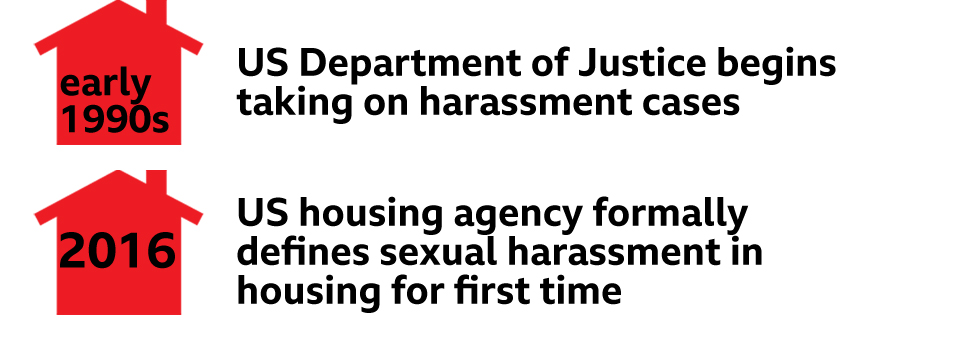

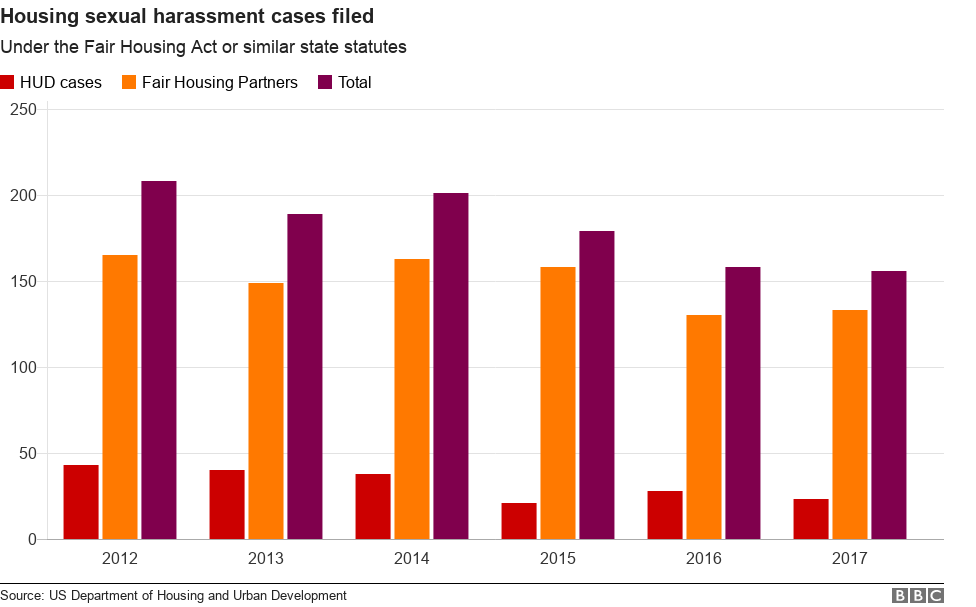

The scant data available on sexual harassment in housing seem to show small numbers of cases like this each year. In the US in 2016, private fair housing organisations recorded 137 complaints of sexual harassment from their clients. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development acted on 28 cases, and HUD-funded fair housing assistance programmes around the country filed 130 cases.

But those numbers may be deceptively low, since a single complaint can reveal dozens of additional victims.

"Finding one victim often leads to finding two, six, 16, 23 - in many of these cases we uncover ongoing harassment of many women over a period of years," says Sara Pratt, the former deputy assistant secretary for Enforcement and Programs at HUD. "That is unfortunately all too common."

The BBC requested data from state civil and human rights agencies and found many cannot easily report how many of their housing cases involve allegations of sexual harassment each year. Of the state agencies that did provide that information, the number of cases per year were in single or low-two-digit numbers. California was the exception, recording dozens of complaints each year, including 159 complaints in 2015.

Lawsuits brought in the private housing market can be settled in complete secrecy, since defendants often demand confidentiality agreements, not unlike the nondisclosure agreements Harvey Weinstein reportedly used to keep women from speaking publicly.

"Powerful men know they have the right to make that request," says Fred Freiberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center in New York City. "I have a strong view that confidentiality agreements are counterproductive and don't serve the public interest."

In total, 16 women came forward in Laurinburg, and of those, six said they had engaged in sex or other sexual activity with one or both men.

The women said that over the years, they had been reporting Pender to Wesley, or Wesley to Pender, without knowing there were allegations against both men.

In a call with the BBC, Wesley says he "categorically denies" all the allegations that were made against him, though he declined to go through them individually. He says the women were motivated by money.

"They lied. There's no better way to say it," he says. "Either they're lying or I'm lying."

Pender did not respond to requests for comment. He denied all the allegations throughout the legal proceedings.

In February 2014, two years into the lawsuit, Four-County was in a state of upheaval. A state audit revealed the agency was riddled with nepotism, and misspent $4.8m (£3.5m) worth of taxpayer money on things like gym memberships and bar tabs. One executive director was fired, and the organisation changed its name to Southeastern Community and Family Services.

Lawyer Kelly Clarke

One thing did not change - Pender and Wesley still had jobs.

Coming forward had been difficult, but so was staying forward in a tiny town like Laurinburg. Other women came up to Sellers to tell her she was putting their housing in jeopardy. She says members of her church questioned her to the point where she stopped going. Rumours flew about possible retaliation. An abandoned home across the street from Sellers' mysteriously went up in flames one night.

"I wanted to give up many times," she says. "It became too scary."

A lengthy case of this nature is typical. Gustavo Velasquez, former assistant secretary of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity at HUD under the Obama administration, says when he first joined the department in 2014, sexual harassment investigations were dragging on for years.

"We were able to bring that number down to nine months. But it really should be 90 days," he says.

HUD became aware of the Laurinburg case about a year and a half after Sellers first came forward. They sent their investigators to Laurinburg, who sent their findings to the justice department. Then the DOJ began its own investigation.

"There were several women who would tell me the kind of things they would do, because they had small children," says a DOJ lawyer who worked on the investigation. "No one should have to make that decision. No one should have to make that choice."

By the time the inquiry concluded, 71 additional women came forward with complaints deemed credible by the justice department. In December 2014, the DOJ filed a federal lawsuit against Four-County.

If you have been a victim of sexual harassment in housing in the US, here is how to report it:

Call the Department of Justice's dedicated hotline for sexual harassment complaints: 1-844-380-6178 or Email fairhousing@usdoj.gov

Call the US Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity at 1-800-669-9777

Contact a local fair housing centre - find yours at nationalfairhousing.org

Pender was placed on administrative leave; Wesley was required to be accompanied by a female employee on any home visits. Security cameras were installed in the offices. But the agency refused to resolve with the DOJ, calling the lawsuit "frivolous".

Finally, in the summer of 2015, HUD sent letters threatening to withhold Four-County's funding if it did not address the sexual harassment complaints. Both Pender and Wesley were finally terminated, and soon afterward, the lawsuit was settled for $2.7m. At the time, it was the largest settlement of its kind in federal housing law history.

The agency's new executive director Ericka J Whitaker released a statement: "I make no pretence of knowing what actually occurred with all parties allegedly involved in this case. What I do know is that fighting an ongoing legal battle is unproductive for the agency."

The Laurinburg case illustrates a larger point of concern - housing authorities and agencies who disburse federal housing benefits are not obligated to record or report the number of harassment complaints they receive each year. They are independent agencies who, in some cities, oversee hundreds of thousands of tenants. Many victims erroneously assume that their only recourse is to complain to the authority itself.

In recent years, the justice department has brought several cases against housing authorities not only for sexual harassment of tenants by employees, but also for failure to act on complaints. A case against the Housing Authority of Baltimore City brought by private lawyers resulted in an $7.9m settlement for a total of 113 victims.

In the Baltimore case, women alleged they had complained to the housing authority for years. A separate union investigation corroborated the claims. But the accused maintenance workers continued on the job while the union safety officer who performed the investigation was fired. The men were not terminated until after the lawsuit was filed.

The demographic make-up of subsidised housing in the US may create a uniquely vulnerable population. National figures show that 74% of Section 8 and public housing units are female-headed households, and one-third of those have children. Public housing policy often bars or severely limits overnight guests, a rule designed to prevent overcrowding that also translates into women who are on their own the majority of the time.

"These maintenance men can be pretty well assured there aren't going to be men around to do anything about what's going on," says Cary Hansel, the lawyer who represented the victims in the Baltimore case.

The BBC reached out to the 16 largest public housing authorities and housing voucher programmes in the US to find out what their reporting policy is for tenants and whether or not they track complaint numbers year to year. Although most respondents said their staff undergo sexual harassment training, procedures for taking tenant complaints varied. Some had no specific policy, some do not keep track of the number of complaints coming in and justified that by saying the number of reports each year are too low.

Major US cities are responsible for hundreds of thousands of tenants - and many don't have standardised tenant sexual harassment complaint policies

The Boston Housing Authority has a civil rights hotline, and policies that require its staff to report any complaint to the police. The Miami-Dade authority says tenants experiencing sexual harassment should call its "fraud investigation hotline". The Chicago Public Housing Authority, the third-largest public housing provider in the country, would not even comment on whether they have a policy.

"Public housing authorities are terrible at doing this," says Velasquez, the former HUD official. "I think housing authorities in large cities - they don't have an excuse."

However, because there is so little research about sexual harassment in housing, it is difficult to say for certain if the problem occurs more often in public housing than the private housing market. Property owners can become landlords without any of the training that public housing employees have to undergo. Since the early 1990s, the majority of the sexual harassment cases brought by the justice department have been against private landlords.

The BBC filed a Freedom of Information Act request in May of 2016 for HUD complaints of sexual harassment going back to 2010, in the hope of parsing out any trends. A year and a half later, the request has yet to be met.

When the 16 original plaintiffs gathered for lengthy mediation and settlement conferences, some were meeting for the first time.

"We pretty much bonded real quickly," recalls Judy. "People started opening up and sharing their stories of what happened."

Sitting in the conference rooms of generic hotels, Sellers says she was struck by the fact that they all had a back story - abusive relationships, substance abuse problems, criminal records - some of which would have shown up on their housing application background checks.

"It's like we all had something that they could feed off of," she says, "and we all needed housing."

"He told my children he'd be their stepdaddy," recalls Candace Stewart, another plantiff in the Laurinburg case. "I didn't want him to come back to my house to do nothing."

In his response to BBC, Wesley saw things in reverse order, that the women's troubles both before and after the case were evidence they're unreliable, untrustworthy witnesses.

"We think that's one of the reasons these cases are so underreported, because the defendants say exactly what John Wesley said to you," says a senior official who is working on the justice department's sexual harassment initiative.

"These women know how they're perceived in society."

Under the Laurinburg settlement - in which neither the agency nor Pender or Wesley had to admit liability - the men will never be allowed to work in public housing again. If they choose to become private landlords, they must hire an independent manager, subject to federal approval.

In some cases, private landlords can be barred from participating in federally-funded voucher programmes. Anna Maria Farías, assistant secretary for Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity at HUD, says her office is working on new policies to ensure once someone is fired from a housing authority for sexual harassment, they cannot join another one.

In truth, the Laurinburg settlement could only fix certain aspects of the women's lives. Kelly Clarke heard from one parent who said the money was the worst thing that could have happened to their daughter, who slipped back into a drug addiction. Another one of the plaintiffs was nearly killed after her abusive boyfriend shot her in the chest.

But others flourished. Judy enrolled in school and achieved her dream of earning her high school diploma. Samantha Oxendine bought a three-bedroom trailer one door down from her mother's, paid in full.

"Right now, I know my kids got a roof over their heads that they'll always have," she says.

Sellers moved an hour-and-a-half away from Laurinburg with her children to a quiet, tree-lined street in Greensboro, North Carolina. She keeps her three-bedroom split level home immaculate, the walls decorated with inspirational quotes and framed family photos. It seems like a world away from the decrepit trailer in Laurinburg where Eric Pender entered her life.

"I'm glad it's over," she says. "I hope he realises what he's done at this point. I don't know if he has."

Sellers now works in mental health services and, in particular, with men and women returning home from prison. Her oldest daughter is about to head off for college.

She says she still suffers intense anxiety as a result of what happened. She lost a lot of friends in the course of the case, and keeps to herself.

But here in her home, Sellers says she finally has a sanctuary.

"It's peace to be able to relax and feel like you're home," she says. "This is mine."