Trump's mental health and why people are discussing it

- Published

It is a question that has dogged Donald Trump - fairly or otherwise - since he was elected president: is he mentally fit for office?

The question has been raised again by the release of a new book by New York journalist Michael Wolff, which chronicles the first year of the Trump White House.

The book - the accuracy of which has been disputed by the White House and queried by others - paints the president as impatient and unable to focus, prone to rambling and repeating himself.

Mr Trump has hit back against Mr Wolff's account, claiming on Twitter to be a "very stable genius" whose "two greatest assets have been mental stability and being, like, really smart".

But the president's manner and speaking style have led to armchair diagnoses of a host of ailments, from Alzheimer's to narcissistic personality disorder - a controversial practice that has divided the medical profession.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

What are people saying?

The current flurry of speculation has been triggered by the book Fire and Fury, in which Mr Wolff writes that during the course of his access to the White House preparing the book, he witnessed people around President Trump become aware that "his mental powers were slipping".

During the marketing campaign for the book, Mr Wolff said Mr Trump, 71, repeated himself often. Repetition can be caused by poor short-term memory, as well as by other factors. It can be a sign of dementia, which affects 5-8% of people aged 60 and over worldwide, according to the World Health Organization.

"Everybody was painfully aware of the increasing pace of his repetitions," wrote Mr Wolff., external "It used to be inside of 30 minutes he'd repeat, word-for-word and expression-for-expression, the same three stories - now it was within 10 minutes."

Mr Wolff did not give any other context for the alleged repetitions. Mr Trump has blasted the book, calling it "phony" and "full of lies" and saying he did not authorise any access to the White House for Mr Wolff.

Critics of the book have also questioned its sourcing. They have asked whether Wolff himself witnessed the events he describes, and called some of its content gossip.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

What have they said before?

Psychologists had previously speculated about symptoms they purported to see in Mr Trump's behaviour.

Several books came out on the topic within months of the Trump inauguration: The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump by Bandy X Lee, Twilight of American Sanity by Allen Frances and Fantasyland by Kurt Andersen.

Dr Lee, who is a psychiatry professor at Yale, told a group of mostly-Democrat senators last month that Mr Trump was "going to unravel, and we are seeing the signs". But it's worth remembering that none of these people have treated Mr Trump, nor do they have close-up information on his state of mind.

Anyone who has treated him would be going against ethics standards and, in most cases, federal law if they disclosed any details.

Why would it matter?

In theory it could cost Mr Trump his job.

Under the 25th amendment to the US Constitution, if the president is deemed to be "unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office", the vice-president takes over. His cabinet and the vice-president together would need to kick-start the process, so it's unlikely to happen, however many voices call for it.

The 25th Amendment: Could it be used to unseat Trump?

Has mental health been an issue for previous presidents?

Yes - presidents have suffered from mental ill health going right back to Abraham Lincoln, whose clinical depression prompted several breakdowns.

More recently Ronald Reagan, who was president from 1981 to 1989, suffered confusion and seemed unsure of where he was at times - he was diagnosed with Alzheimer's five years after he left office.

The 25th amendment has never been used to depose a sitting president.

So what's the evidence with Mr Trump?

It is worth reiterating, there is no real evidence as nobody speaking publicly has examined the president.

But some have suggested that Mr Trump may have symptoms which would point to Narcissistic Personality Disorder, external (NPD).

People with this condition often show some three key characteristics, external, according to Psychology Today:

Grandiosity, a lack of empathy for other people and a need for admiration

They believe they are superior or may deserve special treatment

They seek excessive admiration and attention, and struggle with criticism or defeat

But the man who wrote the diagnostic criteria for NPD, Allen Frances, said a lack of obvious distress stopped him from saying Mr Trump had the condition.

"Mr Trump causes severe distress rather than experiencing it and has been richly rewarded, rather than punished, for his grandiosity, self-absorption and lack of empathy," he wrote.

Wolff's book has prompted some to ask if Mr Trump might be suffering from cognitive decline.

Repetition of stories and the way Mr Trump speaks have been put forward to back up the claims.

When neurological experts compared clips of Mr Trump in the past with more recent footage, external, they found his manner of speaking had totally changed. In the past he spoke in long and complicated sentences, following thoughts through and using long adjectives while in more recent clips, he used fewer and shorter words, missed words out, rambled, and was more likely to use superlatives like "the best".

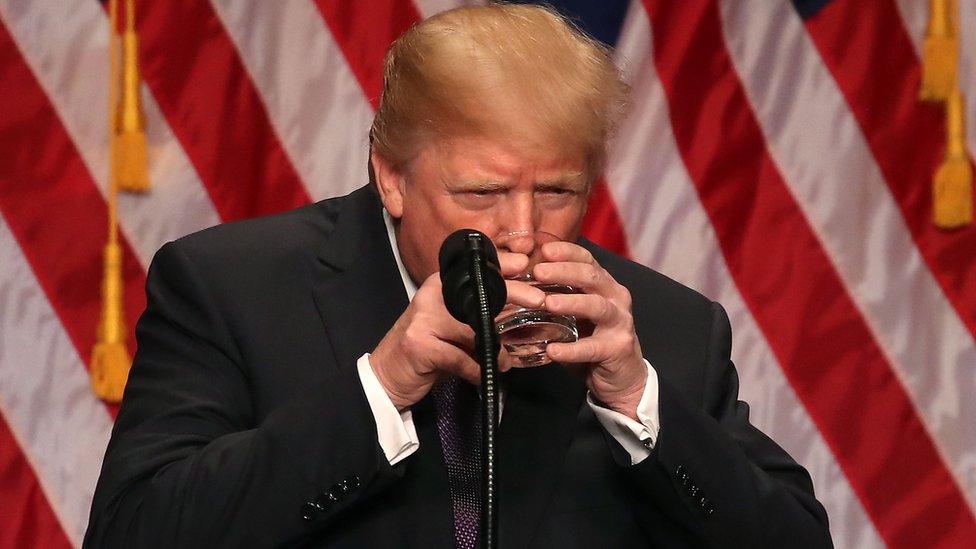

In one instance during a speech in December, Trump lifted a glass awkwardly, with both hands

This could be due to a neurological condition like Alzheimer's, some experts said, or it could be a symptom of nothing more sinister than age.

Those who say the president is concealing cognitive decline point to a few other incidences where he seemed not to have full control over his own movements.

There was one instance in December where he was giving a speech and lifted a glass awkwardly, with both hands.

During another speech, he slurred through some of his words, external, which the White House blamed on a dry throat but some said could be a sign of something more serious.

Viewers were left amazed at parts of Trump's Jerusalem announcement

Motor function is driven by the brain's frontal lobe, which loses volume with age but also gets affected by a specific, relatively rare, type of dementia.

According to the UK's National Health Service, external (NHS), frontotemporal dementia has symptoms including "acting inappropriately or impulsively", "appearing selfish or unsympathetic", "overeating", "getting distracted easily" and "struggling to make the right sounds when saying a word".

Next week the president will undergo his first medical examination - a physical - since taking office.

Is this debate fair?

Well, there's the question.

Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the White House press spokeswoman, said: "It's disgraceful and laughable.

"If he was unfit, he probably wouldn't be sitting there, wouldn't have defeated the most qualified group of candidates the Republican Party has ever seen."

Some Republican lawmakers have dismissed the concerns as a partisan attack.

Representatives Duncan Hunter of California and Mike Simpson of Idaho were said to have "burst out laughing" in February last year when told by news website The Hill that the Democrats were raising such questions. (Mr Simpson did say it was fair to question the president's "judgment", external, however.)

But others have been more scathing.

Following in the footsteps of Jeb Bush's assertion during the race for the presidency that "the guy needs therapy", Tennessee senator Bob Corker said in August that Mr Trump had not demonstrated the "stability" he needed, external for the role.

Dr Frances previously said the debate was unfair - but to people suffering from mental illnesses. "Bad behaviour is rarely a sign of mental illness, and the mentally ill behave badly only rarely," he said.

"It is a stigmatising insult to the mentally ill (who are mostly well behaved and well meaning) to be lumped with Mr Trump (who is neither)."

Others have echoed this, with one columnist saying the debate would "make people with mental-health needs more likely to stay closeted, external".

But professionals who have given their opinion on Mr Trump's psychological state say they have done so in order to warn the nation.

Breaking the Goldwater rule

In speaking out they have in fact broken their industry's own ethics - the decades-old Goldwater Rule prohibits psychiatrists from giving diagnosis about someone they have not personally evaluated.

It was instated after a magazine asked thousands of experts in 1964 whether Republican nominee Barry Goldwater was psychologically fit to be president. He successfully sued the magazine's editor for libel after the results were published.

The APA warned during the campaign that breaking the rule in trying to analyse the candidates in the presidential election was "irresponsible, potentially stigmatising, and definitely unethical".

Given the rule against diagnosing from afar, some argue that there should be a system in place for diagnosing Mr Trump up close.

"A president could be actively hallucinating, external," writes the Atlantic, "threatening to launch a nuclear attack based on intelligence he had just obtained from David Bowie, and the medical community could be relegated to speculation from afar."

In fact there is a law in the works for a committee to be required to assess the president's health - the Oversight Commission on Presidential Capacity (OCPC) Act.

And despite the amount of space given to the topic of the president's mental health, many commentators recoil from it. Carlos Lozada writes in the Washington Post that this is reductive, external: "There is something too simple about dismissing his misdeeds as signs of mental illness; it almost exonerates him, and us."

Former Harvard Law School professor Alan Dershowitz says this approach is "just dangerous", external, writing: "If we don't like someone's politics we rail against him, we campaign against him, we don't use the psychiatric system against him,"

He said people who thought the 25th Amendment would end the Trump presidency were putting "hope over reality".

Only a "major psychotic break" would result in that, he said.

- Published5 January 2018

- Published16 February 2017

- Published4 January 2018