Quebec mosque shooting: A year on Muslims face 'new reality'

- Published

"At some point we said we need to lower the temperature, to step away," says Mohamed Labidi

A year after a deadly shooting in a Quebec mosque, emotions are still raw among Muslims in the Canadian province.

Mohamed Labidi says there was before 29 January 2017 - and there was after.

"We were confronted with a new reality," says the president of the Quebec City mosque where - on a Sunday evening a year ago - a gunman walked in and opened fire during prayers.

The attack on the Quebec City Islamic Cultural Centre left six dead and 19 injured.

Khaled Belkacemi, 60, Azzedine Soufiane, 57, Abdelkrim Hassane, 41, Mamadou Tanou Barry, 42, Ibrahima Barry, 39, and Aboubaker Thabti, 44, were killed, and 17 children were left without their fathers.

Aymen Derbali faces a new life after being paralysed in a 2017 Quebec mosque shooting

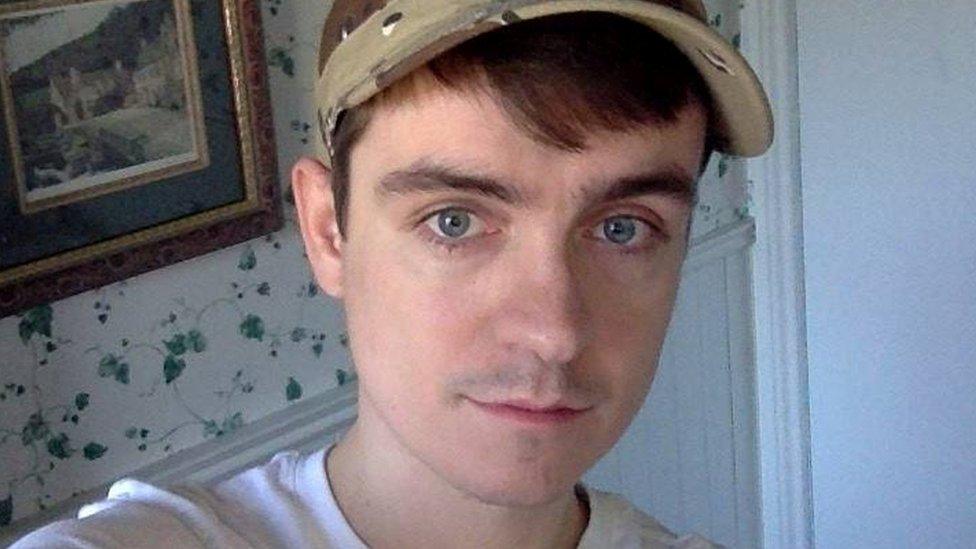

Alexandre Bissonnette, 28, is due to stand trial in March on six counts of murder and five counts of attempted murder.

Labidi says the mosque still receives hateful letters. In August, his car was deliberately torched outside his home.

After that arson, members of the mosque decided to avoid speaking regularly with the media.

"At some point we said we need to lower the temperature, to step away," says Labidi. "It was possible that people who didn't like us, that it was sparking their rage."

Quebec mosque leader describes deadly attack

In the days after the shooting, the mosque opened its doors wide to the world, inviting the media in to tour the grim aftermath of the carnage.

Labidi says they did so to show a violent shooting "did indeed take place in the heart of the mosque, in the place of prayer".

"There were even people killed in the place where they were praying. They didn't have the time to run or hide."

"It was also to show there's nothing to hide in a mosque," he says. "It's just a place for prayer to what we believe is the creator of the world."

In the wake of the shooting, Quebec politicians offered messages of tolerance and unity, and spoke about the need to tone down the divisive rhetoric that had sometimes permeated the long simmering debate in the province on religious freedoms and accommodation.

"When I say words matter, it means words can hurt, words can be knives," said Premier Philippe Couillard, external.

"If we start presenting a foreigner as a threat, a challenge to our identity, something we should steer clear of, that does not advance the idea that we need to try and live together in an inclusive Quebec."

But Hassan Guillet, an imam who gave the eulogy at the funeral of three of the victims, worries the provincial election this autumn means Quebec might return to what he has called a poisoned atmosphere.

Alexandre Bissonnette will go on trial for murder in March

As he took stock of the past year, Guillet says he's been concerned by a number of events.

There was the heated referendum over a proposal for a Muslim-run cemetery in the nearby small town of Saint-Apollinaire. A slashed Koran was sent to the Quebec City mosque in July, days before the vote.

Then there was a baseless news story on a Quebec broadcaster suggesting two Montreal mosques were trying to prevent women from working on a nearby construction site.

The story spread widely in the province, sparking outrage before the mosques denied the allegations and it was debunked.

The broadcaster apologised, external, saying people they interviewed for the report later changed their stories.

And by the end of 2017, the number of police-reported hate crimes targeting Muslims in Quebec City had doubled from the year before.

Guillet was also critical of the rejection by most political parties in Quebec of a proposal to mark 29 January as a national day of remembrance and action on Islamophobia.

Imam Hassan Guillet (left) says Bissonnette 'was not created in a vacuum'

"Alexandre Bissonnette was not created in a vacuum," says the imam of the alleged gunman, who he has also called a victim - to some criticism from Muslims.

Guillet says a debate around state secularism in the run-up to the 2014 provincial election focused a lot of attention on Muslims in Quebec.

The government, then run by Parti Quebecois (PQ), proposed barring the wearing of overt religious symbols or clothing like turbans or hijabs for public employees, and required people to uncover their face when receiving a government service.

While the PQ lost the election to the Liberals, the ensuing discussion - which carried over to the 2015 federal election - has been blamed for fuelling anti-Islamic sentiment in the Canadian province.

"Everything - unemployment, education, equality of men and women - everything was put under the carpet and the whole debate was about the place of religion in society and the place of Muslims in society," Guillet says.

Hassan Guillet delivers the eulogy at the funeral of three victims

In October, Quebec moved ahead with a religious neutrality law that banned face coverings like the niqab when a person is giving or receiving a public service.

Opponents said it unfairly targeted the handful of Muslim women in the province who cover their faces. It's currently being challenged in court, and a judge suspended the ban in December.

Tariq Syed, who recently released a documentary on the shooting's aftermath, Your Last Walk In The Mosque, says the massacre has pulled the community closer to each other and to the broader Quebec City society.

"They are more engaged with the society in general now - talking to the interfaith groups, participating, explaining who they are, about Islam, about the faith," he says.

A young mourner lays her head on one of the caskets during funeral services

Quebecers showed a heartfelt outpouring of support for the Muslim community in the days following the massacre.

Thousands attended an emotional vigil the night after the shooting, and thousands more attended the public Montreal services for some of the victims.

Canadians opened their wallets and donated over C$400,000 ($325,000; £228,000) to the families of the victims.

Men pray at the Quebec City mosque a year after the shooting

Money is also pouring in to help buy a home adapted to the needs of a paralysed victim, Aymen Derbali, who was hit as he attempted to save lives.

Guillet calls the shooting "a weight on our conscience".

"We are Francophone and Anglophone but we are human beings," he says of the emotional response following the massacre.

"We are fathers, we are mothers.

"I don't think anybody likes to see his neighbour killed in such a savage way."

And despite his concerns, he has since seen a "light of hope" that "decent people in society started to raise the flag" in the community's support.

A person holds a sign 'United against Islamophobia' during a rally after the shooting

Worshippers at the Quebec City mosque have experienced the best and the worst of humanity since 29 January.

"The majority of people are of the first kind - that's to say they have sympathy, love, and so on," Labidi says.

"But there is a minority that holds on to hate."

The mosque will hold several days of events to mark the anniversary, including a prayer service, the screening of Syed's documentary, and a vigil.

The commemorations will also pay tribute to acts of solidarity that followed the tragedy.

"We should not let pessimism stop us from dreaming and hoping and working to improve society and our lives," says Guillet.