South Asians in the US: The other 'Dreamers' facing uncertain future

- Published

Many young people who qualified for protection from deportation under an Obama-era scheme are now fearful for the future. While much of the focus has been on Hispanics affected, there's a large group from another part of the world.

Nayim Islam vividly remembers the morning he woke up to the sound of his wailing mother. She had just received a call from back home in Bangladesh. Her father, who she hadn't seen for 18 years, had died.

It was Islam's first year in college and a moment he calls "a turning point" in his life.

Years before, when he was a child, the family had made a tough choice.

They arrived in the US under visitor visas and stayed on as undocumented immigrants. It was a one-way ticket with the hope for a better future. But it also meant living with constant fear of being deported.

As he grew up, Islam says he remembers "feeling very guilty after realising that all her sacrifice may not amount to anything".

"Without documents, I still won't be able to achieve that American Dream my parents had for us."

That moment of feeling "helpless and powerless" as his mother mourned, he says, propelled him to come out of the shadows. He graduated with a degree in biology but decided to become a full-time community organiser.

Daca recipients: 'Life in the US is like a rollercoaster'

That, too, was made possible because of an Obama-era programme - Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals or Daca - that allowed nearly 700,000 immigrants who came to the United States illegally as children to stay and work legally.

In September, President Trump rescinded the programme and has asked Congress to provide a solution by 5 March. Early in January, however, a federal judge in San Francisco ordered the government to resume accepting renewals for Daca and work authorisations.

The administration has now appealed to the Supreme Court to overturn the ruling. Those who benefitted from the programme are faced with uncertainty.

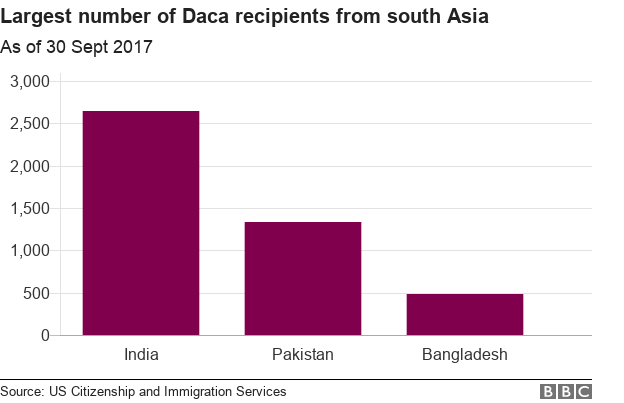

While the majority of the Daca recipients, sometimes known as "Dreamers", are from Latin American countries, there's also a significant number from other parts of the world, including thousands from south Asia. According to data from the US government, external, at least 2,640 Daca recipients are from India, 1,340 are from Pakistan, and 490 are from Bangladesh.

In most cases, the children came with their parents on a visitors visa. The actual numbers of undocumented south Asians are estimated to be higher, as stigma attached with illegal status within the community and fear of sharing family information may have lowered the number of Daca applications.

Shahzeb Leghari was 13 when he moved to New York with his mother and younger brother from Pakistan. His mother had a flourishing business in Lahore, running a boutique and a salon, but decided to leave to escape a rough marriage.

In New York, she worked as a store clerk while he did odd jobs after school in restaurants for $5 an hour.

Leghari recalls being "stopped and frisked" many times in his neighbourhood - a controversial practice where police would detain, question and sometime search civilians without a warrant. For Leghari, it carried the extra worry of being deported and separated from his family.

"It was New York, a so-called sanctuary city. But my heart would be pounding when they searched my bag," he says. "Just one guy had to say - he's a threat - and I would be back in Pakistan."

Things changed after Daca, even though it took him 15 months to get approval because of "extensive background checks". Over the years, the average approval time has been anywhere between three and six months.

"If I had to speculate, I feel it took much longer than usual because I was a Muslim and a Pakistani," he says.

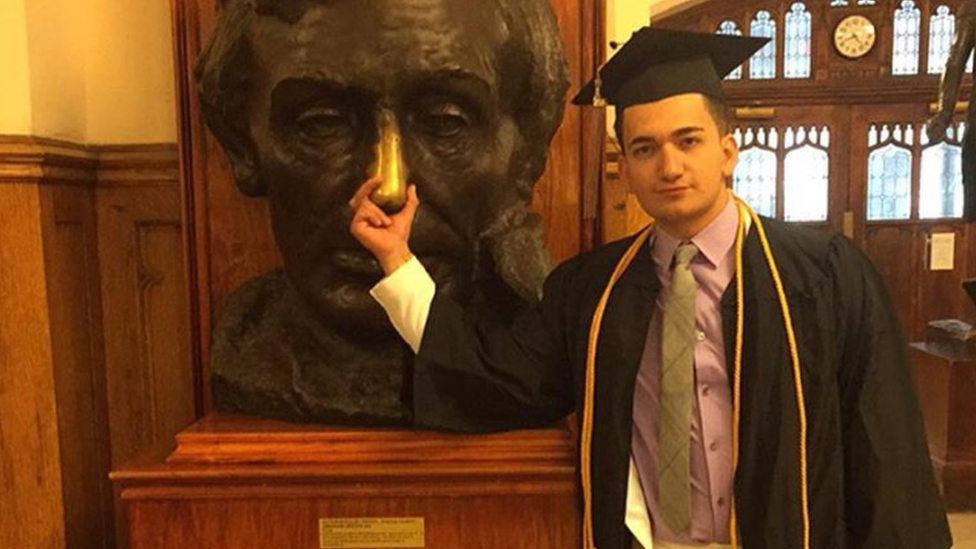

Shahzeb Leghari is studying to be a doctor

He had graduated as a biology major from the City College of New York, but had no hopes of continuing his education in the sciences because of his immigration status. Even if he managed to pay thousands of dollars for a higher degree, there would be no professional job without legal papers.

Daca brought the promise of some financial aid and "on-the-book" jobs. Now he hopes to pursue a career in medicine. While preparing for his medical college admissions test, he also works in a pharmacy, drives for Uber and finds time for community organising.

Like Leghari, more south Asian immigrants are taking part in activism. He says now his family joins him at events, including visiting Washington, DC to participate in protests outside the White House.

But there are many in the community who struggle with English, don't know that despite being undocumented, they have certain rights. And then there's the social stigma.

"Recently, one of my friend's parents were deported to Bangladesh, but he did not let us raise it with authorities fearing that everyone in [the neighbourhood] would get to know that they were undocumented," says Leghari. There's a fear the news will reach back home and the family would be ridiculed and looked down upon by the society where they were considered a success for living in the US.

Nayim Islam now works full-time for Desis Rising Up and Moving (Drum), an organisation that focuses on immigrant rights in the South Asian community in New York City. He says there is a growing realisation among the community that if they do not raise their voice, nobody will do it for them.

Nayim Islam at a protest

"We tend to focus a lot on politics back home, but not on the politics where we are building our lives," he says.

Under Daca, undocumented south Asians did not feel as vulnerable as they used to be, but President Trump's order has put that sense of freedom at risk. Many families are also worried once the security of Daca is lost, they will be exposed and the administration could launch a massive crackdown with information on extended families.

"We don't have a choice but to fight,'' says Islam. "We have to remember even Daca wasn't given to us without a fight."

A recent poll found, external that 83% of Americans and 67% of Republicans support continuing the Daca programme. There is also strong support from large corporations for a legislative solution.

Many Republicans who support Daca beneficiaries also want stringent immigration laws paired with it. But Islam says programmes that save young immigrants from deportation but puts their undocumented parents in danger is not a solution he's going to fight for.

"How can I say that I will accept the path of citizenship in exchange for my parents being deported?"