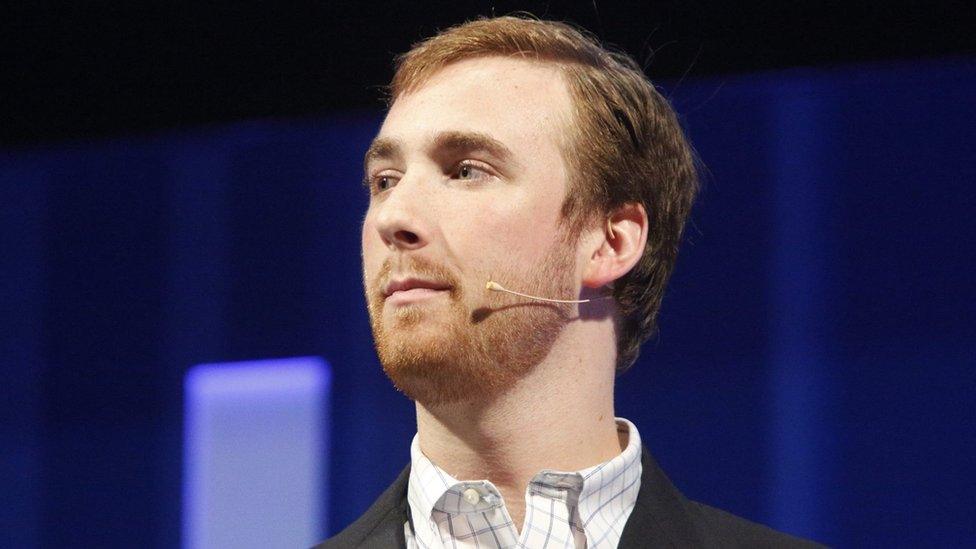

From a broken neck to a Rhodes Scholarship at Oxford

- Published

Highlights of a speech Jay gave at Duke University in 2016

Jay Ruckelshaus broke his neck, almost died, and still can't use his hands. Here's how he fought back to win one of the world's top scholarships.

After this interview, Jay Ruckelshaus asks that his story isn't "cast in a tragedy narrative".

He doesn't want it to be too Hollywood, too sentimental, too saccharine.

"I just have an uncomfortable relationship with inspiration," he says.

So this article starts with the facts, unvarnished.

Jay grew up in Indianapolis, Indiana, in the United States' Mid-West.

At school, Jay ran cross-country, swam, and rowed. He spoke fluent French, played the piano, was part of academic teams and worked in student government.

"I always enjoyed being extremely active," he says.

He won a full scholarship to Duke - a top-ranking university, 600 miles (965km) away in North Carolina - and left high school as a co-valedictorian (an honour for high-achieving students).

Then, in the summer before university, he dived into a reservoir, misjudged the water's depth, and broke his neck.

Jay was on a ventilator for around two months. He had a collapsed lung, couldn't move anything from the neck down, and almost died.

"I had a 109 Fahrenheit [43C] fever from which you shouldn't survive," he says.

He had a month in intensive care in Indianapolis, before spending ten months at a specialist centre in Atlanta, external, Georgia, 500 miles south. His mum moved with him; his dad would visit at weekends.

In Atlanta, he started breathing unaided, regained some arm movement, and was able to eat on his own. He also started using an iPad with his wrist and knuckles.

In 2012, a year later than planned, he started his politics degree at Duke.

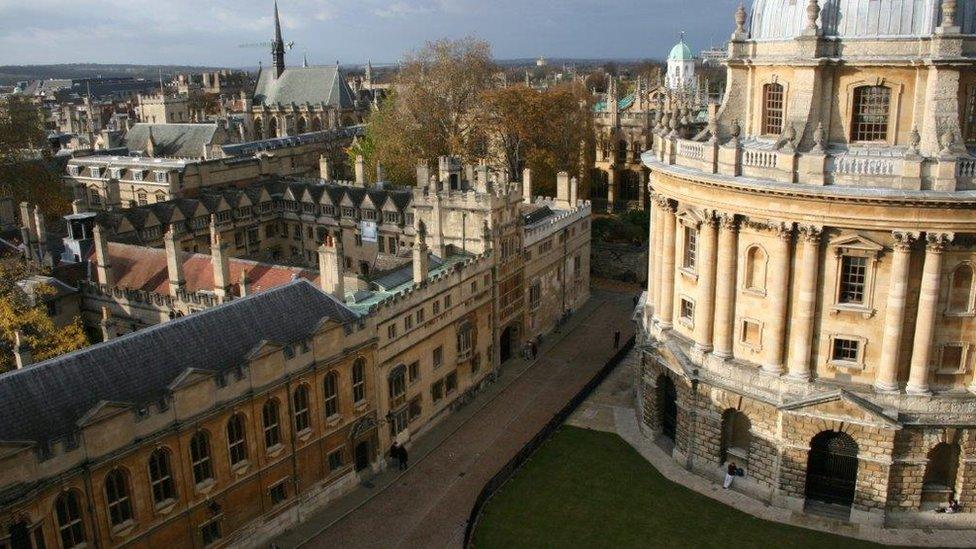

He graduated summa cum laude - with highest honour - and won a Rhodes Scholarship, one of the highest prizes in academia. The scholarship provides all-expenses post-graduate study at Oxford - Jay was one of 32 chosen from 869 applicants, external in the US.

The winners were told after their interviews, in a room with other applicants. "A Miss America moment," he says.

Jay, 25, is now in his second year of his master's degree in England, and hopes to complete a doctorate.

If that were not enough, he also set up a charity, Ramp Less Traveled, external, that helps other students with spinal cord injuries go to university.

So - what's Hollywood about all that?

Jay Ruckelshaus with his mother, Mary, and father, John

Jay's story has a happy ending, but there were dark days in Atlanta, especially early on.

"I felt overwhelmingly like I wasn't where I was supposed to be," he says.

"I was used to setting goals and achieving them, then setting bigger goals and achieving them.

"This [the injury] was not the sort of thing you could out-work, or out-wit, or just stay up late and figure out.

"It's a big rock that you can't move. It was hard to see the rest of my friends go to university, and me not."

Jay had eight hours of rehab a day, strengthening muscles and rediscovering movement. Eventually the milestones came: breathing on his own, eating, using an iPad.

"That [the iPad] was a great thing," he says, because he could operate it himself.

"That allowed me to connect with the world, read the newspaper, read the periodicals I used to read."

To stretch his mind further, he enrolled on courses, buying economics and international relations textbooks.

"Every night I would read them voraciously, because I was bored," he says.

"That was a way I could somewhat stay sane - because otherwise it's the same thing every day."

Jay says his disability is hard to describe in a few words. "Saying [paralysed from] the shoulders down is to underestimate what I can do; saying chest down is to overestimate."

Throughout his rehab, his place at university was a beacon - a world away from rehabs and hospital beds.

Most people, he says, presumed he would change his plans. But for Jay, there was "never any doubt" he would go to Duke.

"I was very adamant from the beginning - this is not changing," he says.

"I was very stubborn about it. There was also no doubt from Duke, which was wonderful, and wouldn't have been the case at some schools."

Despite not being able to use his hands - "I can fake it using my wrist," he says - he was determined to have a "normal, fun" college experience.

"I still wanted to get drunk with my buddies," he says.

He needed domestic help, and sometimes found it hard to "keep up with the spontaneity of college", but soon made a "great" group of friends.

So - in between studying for a first-class degree, co-founding a humanities journal, co-editing a political journal, and sitting on student committees - was he able to get drunk with his buddies?

"Oh yeah," he says, laughing. "Maybe too much."

To apply for a Rhodes Scholarship, students must submit a 1000-word statement, their CV, and eight letters of recommendation.

Jay did not expect to make the final round, so the email, inviting him for an interview in Indianapolis in November 2015, came as a surprise.

He did the interview, met the other candidates - "Incredible people, so smart, interesting, and engaged" - and waited.

The winners were announced in front of everyone. It was "shocking", says Jay, to hear his own name.

"Really, there is no other word," he says. "I had no expectations at all."

As Indianapolis is home, he was able to tell his parents in person. "And that's when it started to sink in," he says.

"It felt good for myself, but it was more a vindication of everything that so many people had done to support me.

"They [Rhodes Scholarships] are not the kinds of things that one person wins on their own, anyway. Everyone has a tribe of people behind them who are supportive.

"But I felt that was especially true in my case."

The Rhodes Scholarship

Former Rhodes Scholars include Bill Clinton [though he didn't finish his degree at Oxford] and former US Ambassador to the UN Susan Rice

At least eight Rhodes Scholars have become heads of government or state

Around 100 scholars are chosen each year, from around 60 countries

The scholarships were created in the will of Cecil Rhodes, the 19th Century British imperialist

It was guilt, partly, that inspired Jay to start his charity.

Towards the end of his first year at Duke, he thought of other wheelchair users - including those he met in the "trenches" in Atlanta - and decided to help.

"I realised I was having an amazing time, taking these amazing classes, meeting amazing people," he says.

"The feeling was almost guilt. Part of it was definitely guilt."

Ramp Less Traveled's goal is to "spread the message that college is attainable for students with spinal cord injuries". It offers grants of $2,500, and mentoring.

So far, eight students have received grants: one was injured at a rodeo; another in a wrestling match. "We've stuck with the model of small and beautiful," says Jay.

But, despite his achievement, he doesn't see his future in disability advocacy. Instead, he plans a career in "some combination of policy and public service".

It's a long way from the ventilator, the fever, and the endless days of rehab. Now, Jay thinks his injury is "not incredibly relevant" to his life.

"In one sense, it sounds disingenuous and flippant to say it doesn't make any difference, because of course it matters," he says.

"It sets up a different set of constraints. But everyone has constraints."

- Published16 November 2017

- Published5 September 2017