Nunes memo: Key extracts and what they mean

- Published

After days - weeks - of breathless anticipation, the secret memo is a secret no more. Was it a bomb or a dud?

Written by House Intelligence Committee chair Devin Nunes and his staff, the memo was being billed by some conservatives as revealing misdeeds "worse than Watergate, external" and offences "a hundred times bigger, external" than what prompted the American Revolution.

Meanwhile Democrats in Congress, and members of Donald Trump's Justice Department, were fighting to keep the memo, warning that it contained "material omissions" and threatened revealing important intelligence-gathering methods.

That's a lot to pack into a four-page document.

So what's the scoop? Here's a look at four key passages from the memo, and what they mean.

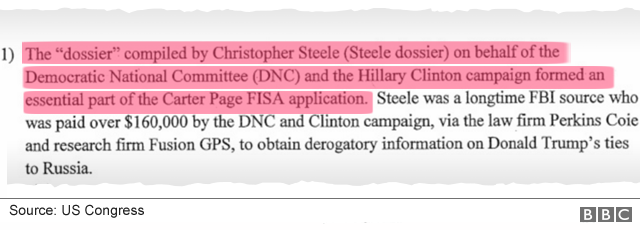

The words "essential part" do the heavy lifting in this paragraph. This sets up the central point of the memo that the application to begin surveillance of Carter Page was dependent upon information contained in the Steele dossier - the collection of raw intelligence information, much of which has not been substantiated and some of which is quite salacious - compiled by former British intelligence agent Christopher Steele.

The memo notes that Steele's efforts were funded in part by the Democratic Party and Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign, although it neglects to mention that the Fusion GPS opposition research effort directed toward Mr Trump was originally bankrolled by a prominent conservative donor and activist.

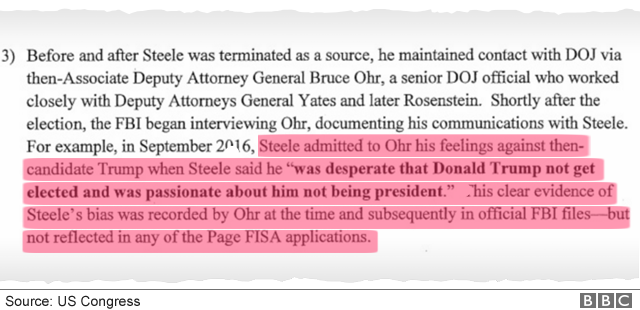

The memo asserts that the FBI did not present evidence of this possible bias to the Fisa judge tasked with reviewing the surveillance warrant - and that this is evidence of, at best, neglect or, at worst, an anti-Trump agenda.

As further evidence of Steele's bias, the memo recounts how Steele, during contacts with a senior Justice Department official, expressed negative views about Mr Trump.

Bruce Ohr, the official in question, made a record of Steele's opinions - somewhat undercutting the accusation of rampant bias within the department, given that a truly compromised individual wouldn't jot that sort of thing down. That notwithstanding, the memo says this information also should have been - but wasn't - included in the Fisa application.

For a bit of context, the Fisa warrant review system was established by Congress in 1978 and, as of 2013, had reviewed more than 35,000 surveillance requests. Of that number, the judges on the court had rejected only 12 applications.

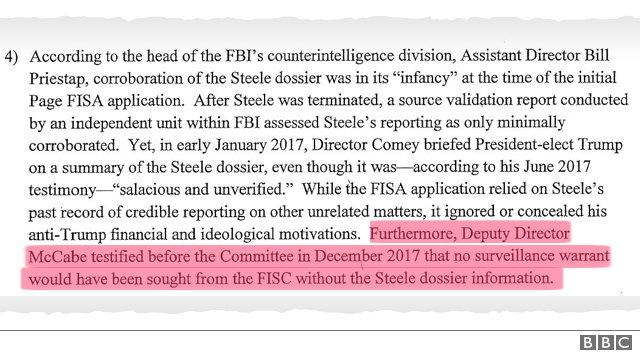

The question, then, is whether knowing a bit more about Christopher Steele's motivations or opinions would have been enough to put this application in the very small pile of discarded requests. Or would the evidence Steele presented, or other information that the Nunes memo may have omitted, have stood on its own and justified the surveillance?

The portion of this paragraph questioning James Comey's decision to inform Mr Trump about the dossier was probably well-received by the president, but it seems irrelevant to the point. It does, however, somewhat mischaracterise, external how the then-FBI director described the Steele dossier.

Yes, Mr Comey used the words "salacious and unverified" - but that was only in relation to portions of the dossier. He declined to comment on the veracity of certain "criminal allegations" in other parts of the dossier - at least in open testimony.

With this in mind, the final line of this paragraph is of particular note. The memo asserts that Andrew McCabe, the then-deputy director of the FBI, testified that there would have been no surveillance request without the dossier.

If this is in fact an accurate characterisation of Mr McCabe's testimony, then it would go a long way toward substantiating the memo's contention that the dossier and the surveillance request are inextricably linked. But without Mr McCabe's actual testimony, this becomes a very big "if".

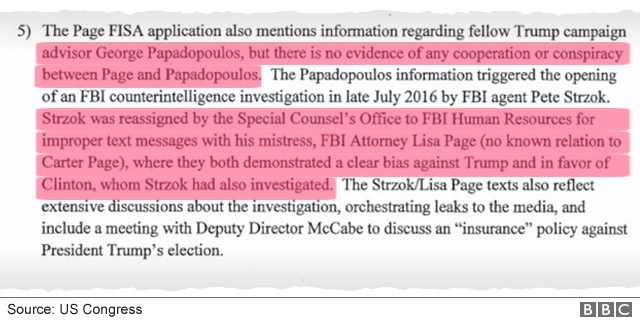

The last paragraph of the Nunes memo contains a somewhat jaw-dropping "oh, by the way" aside.

The memo makes a considerable effort to draw a line from the Steele dossier to the Page surveillance request to questions about the legitimacy of the Russia investigation as a whole. The memo then notes it was information about George Papadopoulos, another Trump campaign foreign policy adviser, that prompted the launch of the FBI counterintelligence investigation in July 2016 - months before the Page surveillance request was granted.

Papadopoulos has pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI about his contacts with Russian nationals while a Trump campaign adviser and was told by one contact that the Russians had "dirt" on Mrs Clinton in the form of "thousands of emails".

The memo doesn't address any of this, instead opting to recount how that investigation was initiated by Peter Strzok, a senior FBI agent who has since become mired in a scandal surrounding an affair with a co-worker in which they made derogatory remarks about Mr Trump via text message on government mobile phones.

George Papadopoulos: The Trump adviser who lied to the FBI

The document concludes with the oft-cited line about an "insurance" policy for the possibility of Mr Trump's election, although it provides no context for this vague reference in an isolated text.

The memo's focus on Page is interesting. The unpaid Trump campaign adviser had been on the FBI's radar since 2013, because of his ties to a Russian bank executive who was later convicted of spying on the US.

Page had resigned as a Trump foreign policy adviser in September 2016 - a month before the Fisa warrant was approved.

The Trump team has characterised Page as a bit player in the campaign, which raises questions about whether an order to monitor Page should be viewed as a direct assault by the FBI on the heart of the Trump campaign, undermining the entire Russia investigation, or a particularly colourful sideshow to a much larger and justifiable endeavour.