Where might Trump go in a nuclear attack?

- Published

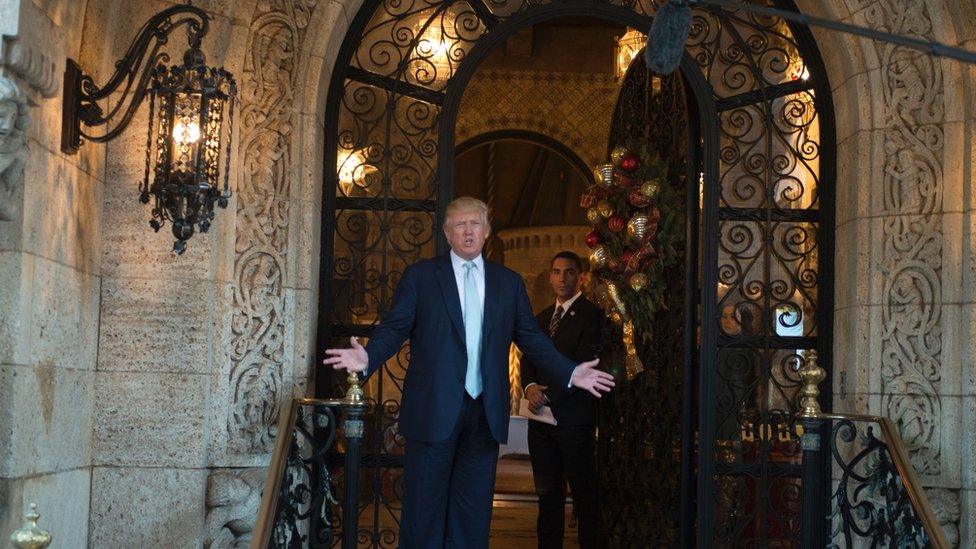

Trump has a bunker underneath his Mar-a-Lago estate - but it has nothing to do with him being president

From Truman to Trump, US presidents have had access to bunkers to ride out a nuclear war. So what happens to the commander-in-chief if a nuclear threat looms?

Almost immediately, President Donald Trump would be whisked to a secure location.

He has a range of places at his disposal. One is located under the White House, a fortified area built in the 1950s. Another is tucked away in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia.

He also has a rudimentary bunker at his Florida estate, Mar-a-Lago, and one originally used to store bombs at his golf course in West Palm Beach (it's under the second hole, according to Esquire, external).

The story of Trump's bomb shelters reflects the ways Americans have tried to grapple with the prospect of nuclear war over the past several decades.

For some people, the idea of nuclear war is unimaginable. Others make plans.

You might also like:

The preparations for nuclear winter, or the war's aftermath, are often elaborate and surprising.

Greenbrier, a former nuclear bunker for Congress, is now a tourist attraction

Yet no bunker, however brilliantly it's assembled, will survive a direct hit.

"There's no defence against the tremendous blast and heat," says Kenneth Rose, the author of One Nation Underground: The Fallout Shelter in American Culture.

If the president survives the initial attack, though, a bunker would come in handy. He'd need a place where he could safely lead the nation - even if the rest of the world was on fire.

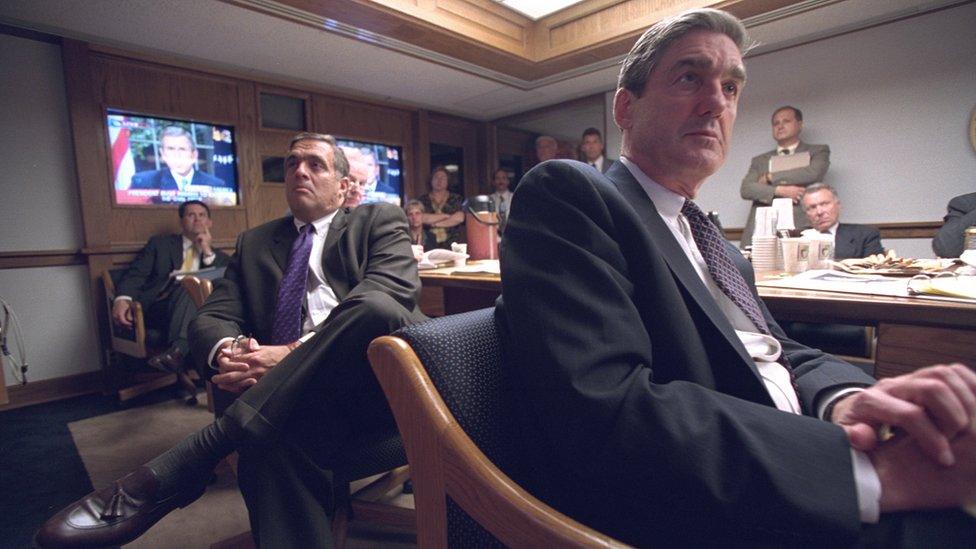

US officials have made access arrangements for the president and a group of individuals deemed to be at the "top of the food chain", according to Robert Darling, a Marine who spent part of 9/11 in the White House bunker. He has described who was allowed in, external.

How could war with North Korea unfold?

As Darling pointed out, only a select few are allowed into a presidential bunker, turning social hierarchy into a matter of life or death. Still historians say bunker building is a necessary part of governmental business.

"You have to maintain a chain of command," says Randy Sowell, an archivist at the Truman President Library in Independence, Missouri. "Or there'd be complete chaos."

The construction of shelters and bunkers, whether for presidents or ordinary people, serves another purpose - they make it easier for Americans to talk about atomic or nuclear warheads and help make the unthinkable - global nuclear war - thinkable.

President Harry Truman oversaw the establishment of a federal civil defence administration in the 1950s. The overall message from the government, said Christian Appy, a history professor at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, was that "nuclear war wasn't necessarily an apocalypse for everyone".

Under the White House, the CIA and FBI bosses listen to President Bush in the bunker-like structure on 9/11

The civil defence agency helped create the idea of "nuclear citizenship", says Appy. The US government wanted civilians to adjust to a new reality, he says, paving the way for their "acquiescence to the nuclear arms race".

A US strategic bombing survey found about 30% of those who died immediately in the US atomic attack on Nagasaki would have been saved by fallout shelters, says Sowell, explaining the rationale behind Truman's civil defence programme.

Officials at the agency tried to set up a nationwide shelter system. Some shelters were built for government employees and members of the public. Officials oversaw the construction of a large facility in Los Altos, California, in the 1960s, for example.

Mainly, though, private individuals built their own bunkers. Thousands were constructed, as Laura McEnaney, a history professor, discovered while researching her book on the subject. "Nuclear war," she says, became "the responsibility of the nuclear family".

One of them, an heiress named Marjorie Merriweather Post, built her bunkers under her estate - the Mar-a-Lago, in Florida.

In the early 1950s, Post was worried about the Korean War and its potential for escalation, and so she built underground shelters. They were dug into the earth below Mar-a-Lago's main building, according to a US interior department survey, external on historic buildings.

Trump bought the property along with the bunker in 1985. He later described, external the underground facility as sturdy, "anchored into the coral reef with steel and concrete".

The ceilings are low, says Wes Blackman. The 6ft 5in former project manager had to duck while visiting the place with Trump years ago.

"It was like we were on an archaeological exploration," he says.

Wes Blackman explored Mar-a-Lago's bunkers with Trump

It was dank, musty and dark, Blackman says. Fold-down cots were attached to a wall. Hand-crank devices brought in fresh air and there was a toilet in the middle of the room.

While Post was building her bunker at Mar-a-Lago, US officials were making contingency plans for Truman at the White House.

The officials wanted a secret location with "a whole governmental complex set up there," Sowell laughs - as if the idea were absurd. Yet he also knows that the place, however unlikely, exists: it's 50 miles outside of Washington.

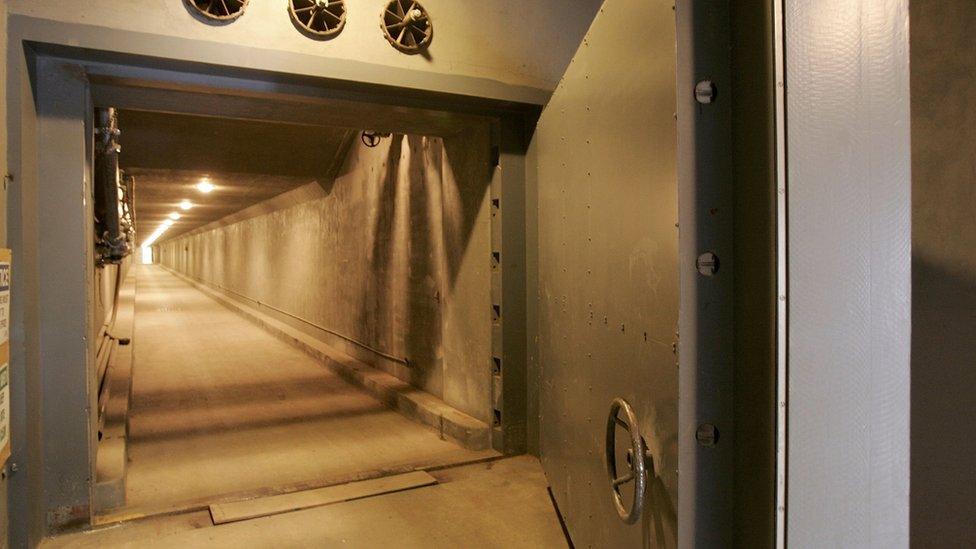

Mount Weather, a 1,754-ft (534m) peak near Bluemont, Virginia, was turned into a giant bunker for the president, his advisers and others to hide in case of nuclear attack.

Members of Congress would be taken to a bunker at Greenbrier resort near White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. The facility had a code name, Project Greek Island, and operated for decades - until its existence was revealed in the media in 1992 when the bunker was "decommissioned".

Mount Weather is now run by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (Fema) and was "activated" after the al-Qaeda attacks in September 2001, a Fema director testified to Congress in October of that year. He didn't provide details.

Mount Weather was hollowed out for a presidential bunker

The facility could theoretically provide shelter for Trump after an attack.

People who live in the area are curious about Mount Weather, or Doomsday City, as it's also known.

Hailey Roberts, a student at Patrick Henry College in Purcellville, describes it as "distant and secretive". Luke Shanahan, also a student, says he's driven past the place many times and studied it from a nearby hill. "It's got multiple helipads," he says.

In the autumn of 1961, construction began on another presidential bunker. This one was created for President John F Kennedy in Florida. It's not far from Mar-a-Lago - the US Navy's Seabees built the bunker on Peanut Island, a 10-minute journey from a Palm Beach house where Kennedy often stayed.

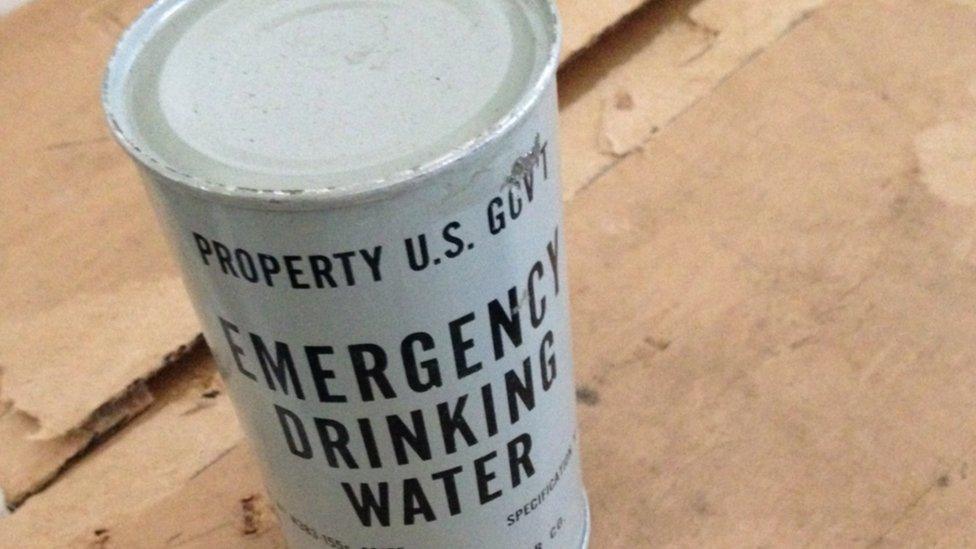

Kennedy's bunker was designed to protect him from radiation

The bunker was known as Detachment Hotel, and it cost $97,000 to construct, according to a 1973 report to Congress.

Kennedy came to the place a couple times. "He did the drills," says Anthony Miller, who until recently ran a museum located on the island.

The Cornwall native took me there on his boat. The bunker is a corrugated shed under 12ft of dirt, with sand pipers poking the grass outside.

"Pretty much a hole in the ground," Miller says. He pulls on a door handle, and it squeaks. Holding the rusty lever, he says this is "where the leader of the free world would have run the country".

Kennedy's bunker was outfitted with basic supplies

The presidential bunkers, whether at Mount Weather, Peanut Island or Mar-a-Lago, were built during the Cold War. It was a time "of foreboding", says Sowell, but belief in preparation; a period in history when children were told to cover themselves to prevent being hurt by radioactive fallout.

Blackman says that he saw no need to fortify the bunker at Mar-a-Lago for Trump. "If Armageddon is unleashed," Blackman says. "There is nowhere to hide." The bunker there was used to store tables, chairs and patio moulding.

Still Blackman says he understands the need. He told me if the world fell part, he'd go hide at his lake house, where he lives with his two Welsh corgis.

"Maybe we all build bunkers in our own way," he says. "Sort of like your security blanket - your safe place."

Who's allowed into a presidential bunker?

Peanut Island: The president and a couple of dozen aides and secretaries (there was room for 30).

White House: Vice-President Dick Cheney worked behind the bunker's "steel door" on 9/11, says Darling, along with the vice-president's wife; Condoleezza Rice, the national security adviser, Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and others. (President George W Bush spent the day on Air Force One.)

Mount Weather: There's room for the president, his aides and hundreds of others - even journalists (a press room was built).

Follow @Tara_Mckelvey

- Published18 January 2017