The woman still protesting over Martin Luther King

- Published

Jacqueline Smith outside the Lorraine Motel

Jacqueline Smith has spent 30 years protesting outside the motel where Martin Luther King was fatally shot in 1968. After being forcibly removed from the premises when it closed, she has devoted her life to protecting his legacy.

As the motel door of room 303 was prised open with a wrench, four police officers burst into Jacqueline Smith's home of 11 years, picked her up and carried her along the balcony, down the steps and on to the street below.

The last resident of the Lorraine Motel - and her possessions - were being removed. Smith's eviction was captured on page 16 of the New York Times, external that day in March 1988, under the headline "Eviction empties motel where Dr King died".

"You people are making a mistake," Smith said, while sobbing.

"If I can't live at The Lorraine, I'll camp out on the sidewalk out front."

Thirty years later, Smith remains there.

Jacqueline Smith was evicted from the Lorraine Motel, along with her possessions

At the corner of Mulberry and Butler Streets, away from Memphis' bustling Beale Street, you'll still find Jacqueline Smith. Dressed in a black hat, scarf and dark clothes, she sits at a table, surveying the scene from behind her sunglasses. Pointedly, she has her back to the Memphis memorial to Martin Luther King.

The National Civil Rights Museum opened to the public on 4 July 1991, 23 years after the assassination of America's most famous civil rights activist. The recognisable facade of the Lorraine Motel has been maintained, with a wreath hanging from the balcony in front of room 306 and two replica vintage cars parked outside.

"Being forcibly evicted from my home was a very traumatic experience, especially when the reasons for my eviction were just plain wrong," Smith says.

"Being homeless, I felt I had had no option... I chose to stand up and protest about how poorly people were being treated and how easy it would be to make a real difference to the people who need it most.

"Thirty years on, I still feel the same."

During that time, Smith has met thousands of visitors "from all over the world" who have "lifted my heart" with their hunger for knowledge.

"I have to explain that I have no problem whatsoever with a National Civil Rights Museum, but I truly believe that the Lorraine Motel is capable of being so much more than an empty space."

The site of the motel was purchased by the Lorraine Civil Rights Museum Foundation, which operates the museum, for $144,000 in 1982. Construction cost $8.8m (£6.2m) and was jointly financed, external by the state of Tennessee, the city of Memphis and surrounding Shelby County.

Jacqueline Smith's signs change but her position does not

Hundreds of millions of dollars of investment has since transformed this part of Memphis, particularly during this decade, explains historian Jimmy Ogle, a lifelong Memphian.

"You can't build apartments or condos fast enough in that area, whether it's new buildings or rehabbing old warehouse buildings that are 100 years old," he says.

"All through the 1980s, 90s and early 2000s, there has been a renewal of the area. And when you have things like the National Civil Rights Museum... you've started having I guess what you call gentrification."

Smith believes the museum is a tourist trap which focuses too much on the violence of King's death instead of the work he did when alive.

"We've seen the glorification of death and negativity with the multi-million dollar purchase of the rooming house from where Dr King was shot. We've seen gruesome artefacts purchased and displayed and we've seen the Lorraine motel host countless black tie dinners where the limousines and ball gowns grace the streets.

"But what we've seen most is the complete disconnect between Dr. King's dreams and aspirations and what the Lorraine actually offers today."

The museum has caused "devastation" to a "community which has been systematically dismantled, uprooted and relocated against their will," she says.

Signs around her stall describe the museum as a "monument to injustice" which "desecrates the memory of Martin Luther King Jr".

People need a place to pay their respects to Dr King, she says, but it would be better if they could see his work in action.

"Support for the homeless and disadvantaged, healthcare and help for the old and infirm. These are the issues that mattered to Dr King and they still matter today."

Commemorations marked the 50th anniversary of King's death

Mark Russell, executive editor of the Commercial Appeal, a major Memphis newspaper, describes Memphis as "the nation's poorest big city".

"It has a huge number of children living in poverty, income inequality and a high unemployment rate for African-Americans while at the same time having a thriving logistics and banking industry.

"It's a tale of two cities, so King would think there's still work to be done in Memphis."

The museum which attracted 350,000 visitors in 2017, declined to comment. But its website says admission fees "go toward the upkeep of the museum and advancing its educational mission through special programs and the work of our staff".

As well as learning about the history of slavery in America and the civil rights movement, visitors can see inside King's bedroom. The museum recently completed a $28m (£19.8m) upgrade.

Then Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi (right) with US President George W Bush

Presidents, prime ministers and politicians have all passed through the museum. George W Bush brought Japan's Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, Hillary Clinton stopped by in 2008.

When former US President Jimmy Carter visited the site in 1991, he refused to enter the museum and instead stood for photographs with Jacqueline, according to The Independent newspaper, external.

Fifty years on from King's assassination, what would the man himself make of her peaceful protest?

"Without wishing to sound arrogant, I think Dr King would approve of my work," Smith says. "He was entirely focused on making things better for people and in my own small way, I'd like to think I'm following his example.

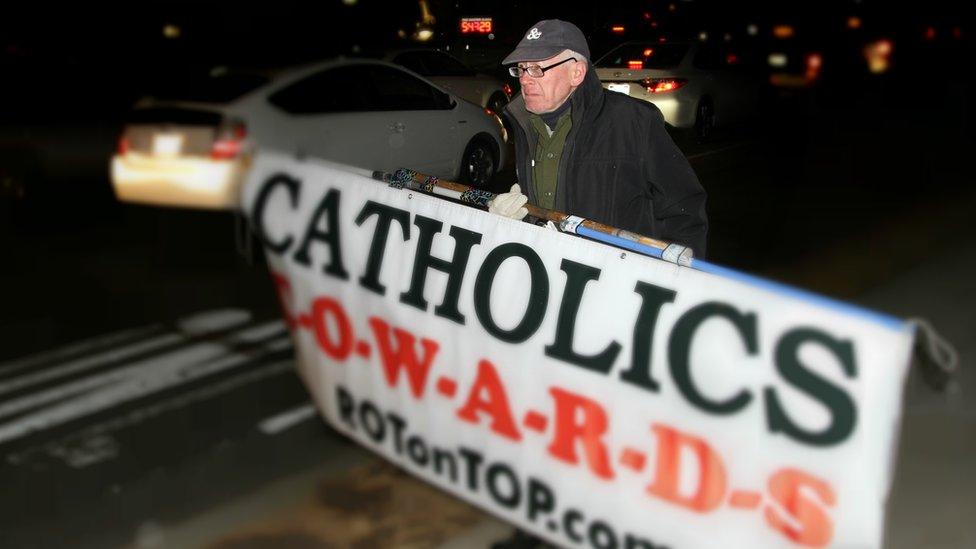

Other long-term protests

John Wojnowski was abused by a priest during a Latin lesson 60 years ago and has spent the past two decades protesting outside the Vatican Embassy in Washington DC.

Peace protester Brian Haw camped outside Parliament in London for 10 years, from 2001 to 2011. He died the same year

Concepcion Picciotto, a peace campaigner, camped outside the White House from 1981 until her death in 2016