Oklahoma teachers: 'Our education system has failed'

- Published

"I have 29 textbooks for 87 pupils": Why these teachers in Oklahoma are striking

Teachers in Oklahoma are the latest to walk out of classrooms in protest at sharply cut education budgets. They say what happened to their schools should be a warning for other states.

To the red country of Oklahoma a stiff and steady breeze came from the west, stirring the redbud trees and setting their deep purple flowers atremble.

It may be spring in the American heartland, but for many teachers here it's not a time of optimism and renewal, but of decay and despair.

"I am exhausted constantly," says Chelsea Herndon, a full-time high school biology teacher who also works up to 30 hours a week as a veterinary technician.

"I don't know what being well rested feels like anymore," she says, moments after treating a mauled dog.

At weekends and on Wednesday nights Ms Herndon toils until 2am at the Animal Emergency Center in Oklahoma City. She has to be back in the classroom at around 7:30am.

The children, she says, are being short-changed.

"They see their tattered textbooks. They see their tired teachers. They know Thursday mornings Miss Herndon's a little grumpy - she needs some coffee!

Chelsea Herndon at her second job

"So they see it and they want better. They definitely want better."

Last year, Oklahoma's education spending per pupil was 28.2% less than it was in 2008, before the Great Recession struck, according to the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The National Education Association, which represents publicly funded school staff, calls these cuts "the deepest in the nation".

Gina Muscari, who teaches second grade at Crutcho Elementary, a rural school outside Oklahoma City, says her students miss what's been cut.

"We used to have a really cool art programme," she says, but there's no funding for it.

"We used to have choir, all sorts of music… I would love a school nurse. I would love a full time counsellor."

They have new textbooks, she says, but "only because we have saved for 10 years".

Crutcho is now open four days a week, rather than five, to save money on buses, electricity and support staff.

Of the state's 1,820 publicly funded schools, 207 have moved to four-day weeks, according to Christy Watson of the Oklahoma State School Boards Association.

And many Oklahoma schools are struggling to retain qualified, talented staff. When one teacher left Crutcho Elementary recently, Muscari and a colleague split the extra pupils between them.

"Our kids really, really feel the impact," she says.

This crisis follows a decision by the state legislature to sharply reduce taxes in response to the recession, with the aim of encouraging investment and growth. The move was driven by small-government, pro-business Republicans but was also supported by many Democrats.

School buses outside Crutcho Elementary

Other states tried the same approach, notably neighbouring Kansas, but few continued cutting as the economy began to improve. Oklahoma was among just a handful of states still reducing school budgets in 2016-17, when funding fell by another 8% over 12 months, second only to Wyoming.

Some Oklahoma Republicans now think they went too far.

"Any successful society from the Roman Empire [onward] has had to have some form of government," says Leslie Osborn, a Republican member of the state House of Representatives.

Osborn says she has changed her mind about the extent to which tax cuts can boost economic growth.

She was in favour of the theory that cutting taxes to the bone would spur growth, she says, until the outcomes - "not enough troopers on the road, not enough foster care workers to take care of children, not enough teachers in the classroom" - made her think again.

"I've been called a RINO - Republican in Name Only" she says. "I don't believe that's true. I believe that a good Republican can be compassionate, can believe that we need a safety net for people."

That's why Osborn strongly supported a move by the state legislature last week to approve modest tax rises on oil and gas production, fuel and cigarettes. The extra revenue will be used to boost school funding and increase teacher pay by an average of $6,100 (£4,340) per year.

The bill was signed by Governor Mary Fallin on Thursday, despite opposition from some powerful figures in her party, including former US Senator Tom Coburn, who made a last-minute plea to fellow Republicans.

The Oklahoma Oil and Gas Association is also critical, announcing its "firm and complete opposition" to an increase in the production tax paid by the industry - from 2% to 5% - which is still lower than other oil-producing states.

"The reality is oversight, efficiency and reducing waste and fraud should be the focus at the Capitol," Association President Chad Warmington said in a statement.

Teachers are not satisfied either. The pay rise sounds a lot until you consider the context, says Ms Herndon, the veterinary technician who also heads her school's biology department.

She has 10 years of experience as a teacher and makes $33,000.

"If I go to Texas I'm starting at almost $50,000 a year. So it's a pretty big difference."

Oklahoma is right at the bottom of the barrel for teacher pay in the US, along with West Virginia where striking teachers recently won a 5% rise. Their success stirred disillusioned educators into action here, but also in Arizona and Kentucky.

Teachers continued their walkout on Tuesday to rally for higher pay and education funding

Muscari describes the emergency measures as "a drop in the bucket" after "really deep cuts every single year in education funding for 10 years in a row".

A couple of hours drive across the plains from Oklahoma City, she has an ally in Gary Jones, a rancher who is seeking the Republican gubernatorial nomination later this year.

Jones is not afraid to style himself as "the only candidate in favour of increasing taxes".

He insists he is a dedicated conservative who nonetheless believes that the creed of smaller government and lower taxes can be taken too far.

"It's got to be a balance," he says. "It's easy to go out and pander to voters and tell them that I'm going to cut, cut, cut."

A desire for efficiency, he argues, must be tempered by the ability to effectively deliver the core services expected from government.

That could also be a message for Donald Trump, who is now embarking on a similar course of action at the federal level, albeit with added borrowing thrown into the mix.

The president is enormously popular here in Oklahoma, and Republicans are wary of criticising him directly. But Jones and others admit to deep concerns about what the long-term effect on public services will be after slashing taxes and increasing short-term spending and borrowing.

Teachers are rather more forthright.

"There's days that I'm so angry, I'm disgusted," says Teresa Danks who teaches at an elementary school in Tulsa.

"It's embarrassing to say this is what I make. I have a master's degree in education!"

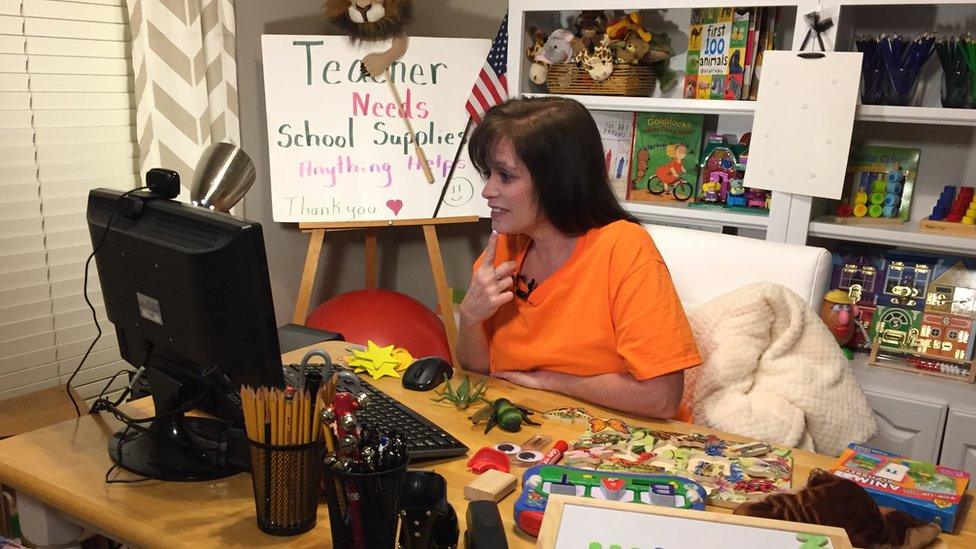

Teresa Danks

She starts work at 5am in front of her home computer, where she tutors students half way across the world, in China.

She makes more money per hour doing that, she says, than she does at Grimes Elementary, where she arrives around 7am to begin her second shift of the day. After the school day is over, Danks returns home to work on grading and lessons plans, as well as teaching more online classes.

Danks points out that everything in her classroom, except for the furniture, is paid for out of her own salary. She caused a stir last year when she was filmed begging for money for school supplies on a street corner.

"We are begging for our voices to be heard as teachers," she tells me. "We're begging for the state of Oklahoma to put education as a priority."

Danks is worried other states are following in Oklahoma's footsteps.

"Our education system has failed... and it is failing a lot of places across the United States. It is failing our children."