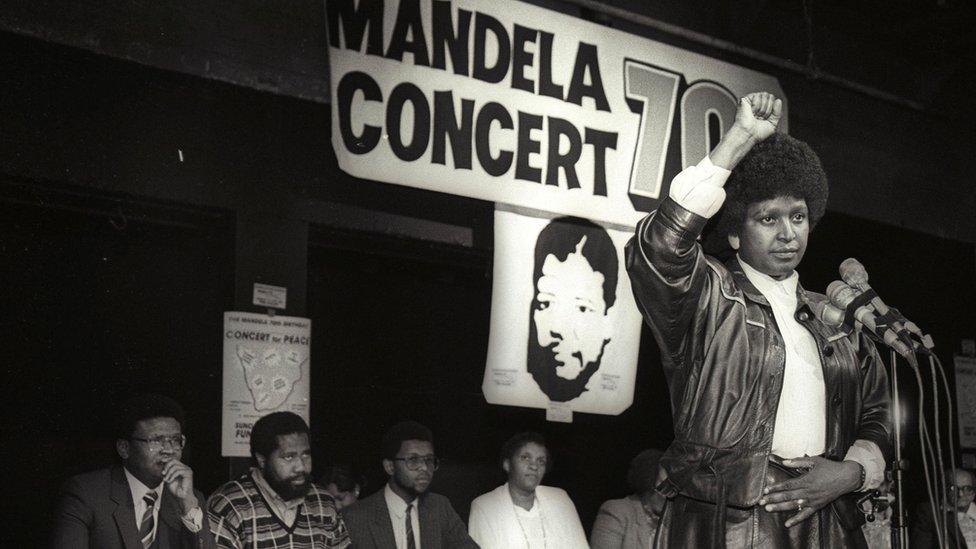

My friendship with Winnie Madikizela-Mandela

- Published

Winnie Mandela and Gary Bedell

Canadian diplomat Gary Bedell first met Winnie Madikizela-Mandela when she accompanied Nelson Mandela on his first visit to Canada and the United States, shortly after his release from Victor Verster prison. Bedell developed a deep friendship with Madikizela-Mandela - a woman he describes as "bigger than life" - that spanned over two decades. He shared his story with the BBC.

It was the summer of 1990, and Gary Bedell found himself standing on a New York City sidewalk arguing with Winnie Mandela.

The wife of Nelson Mandela was adamant.

She had made her own indelible mark as an anti-apartheid campaigner, a central member of the struggle, during her husband's long imprisonment.

And so she would indeed be attending an important meeting with business leaders at the World Trade Centre with the rest of his delegation.

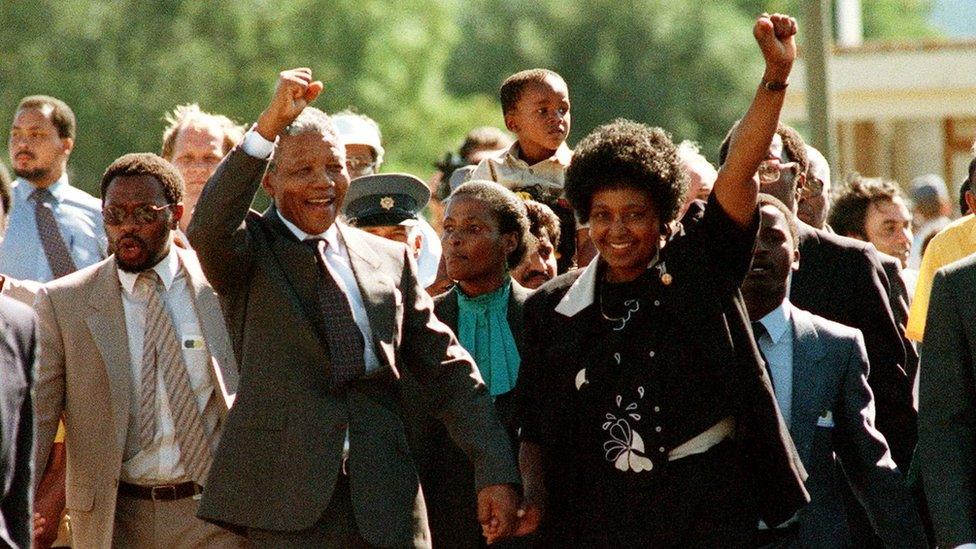

Nelson and Winnie Mandela on his release from prison in February 1990

She was definitely not going to appear instead on The Phil Donahue Show, as planned.

"Send somebody else to go talk to the housewives of America," Mr Bedell recalls Mrs Madikizela-Mandela telling him. "Why does it have to be me?"

Mr Bedell was sympathetic, but Mr Mandela had urged him: convince her.

"She was not going. Stubborn as she was," the former diplomat recalls.

"In the end I just said: 'You're going to be the one to lose because it's going to be a blank screen and it's going to say: Winnie Mandela didn't show up.'"

Mrs Madikizela-Mandela relented, and her appearance on the talk show - broadcast at the time to almost 200 cities across the US - was a triumph.

"Leading crowds in her 'Amandla!' (Power!) chant and hailed from midtown television studios to Brooklyn street corners as an inspiration and a role model for African American women, the anti-apartheid leader delivered potent messages with unflappable dignity," wrote the Washington Post at the time, external.

The Canadian diplomat - tasked with organising Nelson Mandela's first visit to Canada when he was months out of prison - had met the Mandelas just weeks before.

Mr Mandela - still coming to terms with the new realities of his freedom - was grateful for Mr Bedell's advice on protocol, and they developed a rapport.

He also appreciated Mr Bedell's ability to appease Mrs Madikizela-Mandela's "fierce personality", once joking that the diplomat handled her better than he did.

So Mr Mandela asked Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney if Mr Bedell could continue to accompany the couple, joining them on their visit to the United States.

Mr Bedell and Mrs Madikizela-Mandela soon formed their own bond over mutual attempts to ensure Mr Mandela, then 72, was given enough time to rest during their whirlwind three-week US tour, which included a ticker tape parade along lower Broadway and celebrities and politicians jockeying for his time.

Mrs Madikizela-Mandela too was good, he remembers, showing political instinct and a natural charisma, charming journalists who tried to press her on scandals back home.

Nelson Mandela, Gary Bedell, and Winnie Mandela

But amidst the pomp of the tour, Mr Bedell noticed the couple had a naïveté about them.

At a glittering celebrity fundraiser in New York, hosted by Robert de Niro, attended by the likes of Eddie Murphy, Robin Williams, and Spike Lee, Mr Bedell says: "Winnie turned to me and whispered: 'Who are all these people?'"

He also noticed early strains between the newly reunited pair.

Mrs Madikizela-Mandela was a "very vivacious and passionate woman" and the man she had married had aged during his 27 years in prison.

"You almost got the sense he was more of a father figure to her than a husband at that stage," he says.

Those tensions were more obvious when, a few months later, Mr Bedell flew to South Africa at Mr Mandela's request to develop a training programme for protocol staff and to reform their security teams.

The challenges Mr Mandela faced as he led the African National Congress in its negotiations for an end to apartheid and worked towards forming a new, multi-racial democracy were obvious.

Mr Bedell says nobody carried more pressure than Mr Mandela in the years between 1990 and 1992.

"In private he often exploded," he says.

"The language was incredible, like a truck driver."

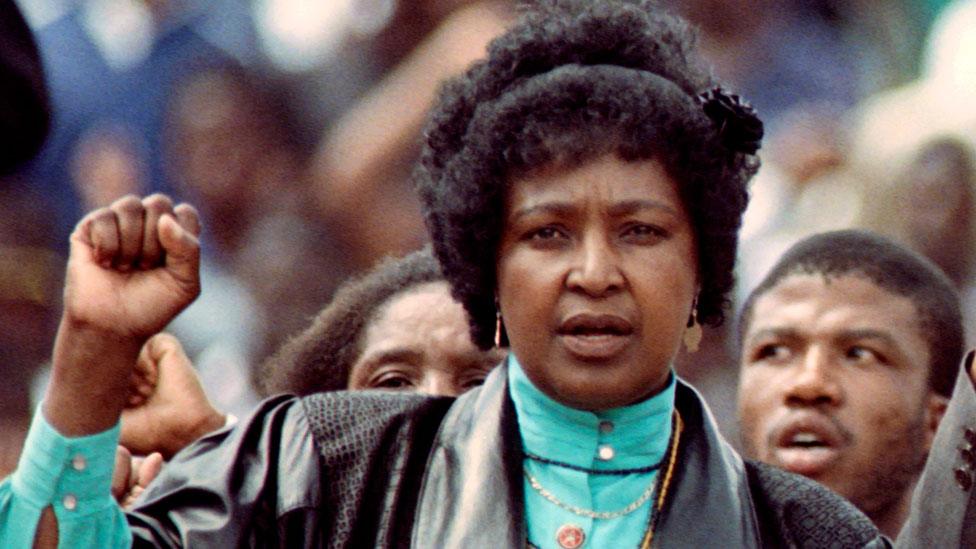

Winnie Mandela being arrested in 1991 while staging a protest calling for the release of detainees on hunger strike

Mrs Madikizela-Mandela had her own personal trials.

She had been frequently detained during her husband's incarceration - jailed and placed in solitary confinement for her activities, banished to a rural area by apartheid authorities, her house burned down.

She raised the couple's daughters alone.

Her resistance in those years led to her being dubbed the "Mother of the Nation".

In her family's recent words, she became "one of the greatest icons of the struggle against apartheid".

She told the BBC in 1986 the experienced changed her.

"All I know is I am terribly brutalised inside. I know my soul is scarred," she said.

Now, she was feeling pushed aside as her husband campaigned for a moderate path towards his goal of national reconciliation.

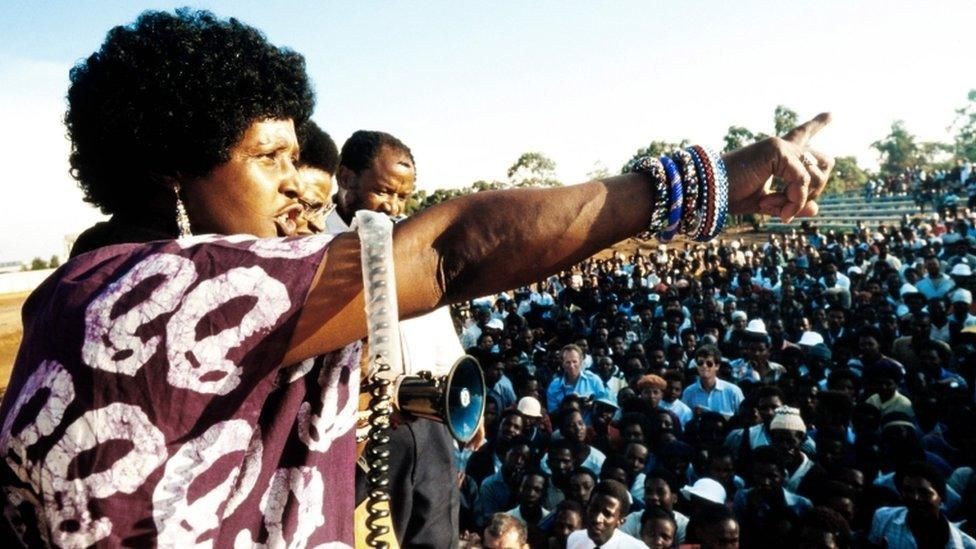

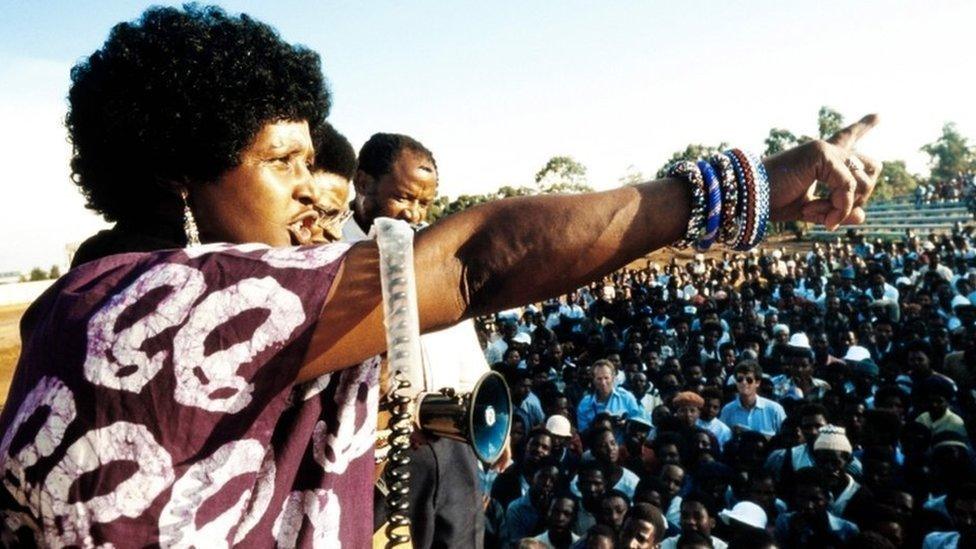

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, then-wife of Nelson Mandela, addressing a meeting in Kagiso township in 1986

"She was terribly upset at the fact everyone wanted to treat her as Mrs Mandela - as opposed to the very extraordinary role she had played when he was in prison," Mr Bedell says.

One of Mrs Madikizela-Mandela's reactions was "to become even more outrageous and more revolutionary in her rhetoric, which of course didn't help her public reputation, or even Nelson's".

No doubt as a result of her traumatic experiences, she was also drinking and taking painkillers.

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela

Mr Bedell hatched a plan to secretly bring Mrs Madikizela-Mandela to Canada to get a handle on her drinking, under the guise of a vacation in the Muskokas, in central Ontario's cottage country.

Mrs Madikizela-Mandela backed out days before she was supposed to board the plane.

"Mandela was heartbroken, he was deeply disappointed she hadn't gone," says Mr Bedell.

Not long after, the couple separated, the marriage finally broken by Mrs Madikizela-Mandela's affair with a young lawyer.

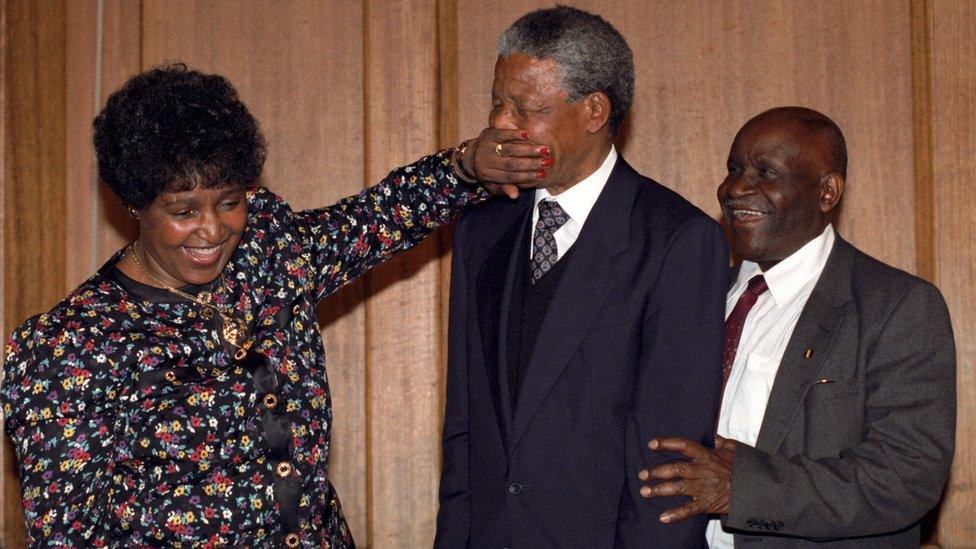

Nelson Mandela is playfully silenced by Winnie Mandela as they leave a London press conference in 1990

World opinion had also turned against her.

She had been convicted of kidnapping 14-year-old Stompie Sepei, and many believed she was guilty of far worse crimes.

There was the adultery against her venerable husband and incendiary comments, including condoning brutal violence against those seen as traitors.

She faced corruption allegations, and was later convicted of fraud.

Mrs Madikizela-Mandela, now divorced and having taken her maiden name - Madikizela - while also keeping his, was accused living off her former husband's name.

"The public was set against her in terrible ways, and she invited much of it of course," Mr Bedell says.

But he had tremendous sympathy for his friend, and stood by her side.

"When the public opinion decides it wants to hate a woman, it's always much, much worse than when they decide to hate a man," he says.

In his eyes, she was as flawed as any human, making the wrong decisions but paying too steep a price for them.

Someone who had endured too much pain and too many indignities.

Mrs Madikizela-Mandela (pictured in 1988) became a symbol for the anti-apartheid movement in her own right

He adored Mrs Madikizela-Mandela - for her strength and intelligence and the affection she showed to those around her in private.

In later years, he watched her being a doting grandmother, and handling her financial struggles with "great dignity".

He says Mrs Madikizela-Mandela often spoke with nostalgia about her abandoned dream of becoming a social worker.

"She deeply regretted that the circumstances of her marriage and politics took her away from what she always loved more and what she wanted to be," he says.

"She never got to just be Winnie, the social worker."

Now, he says she is suddenly gone and South Africa "has to reconcile what it will be without her".

He thinks history will be kinder to her memory than it was during her lifetime.

"Despite all that hatred that the world threw at her, despite everything the South African police and the government did to try to destroy her, despite all of her bad decisions, the divorce from Nelson, her bad business deals, Winnie's the one who lasted. Winnie is the one who made it to the end," he says.

- Published4 April 2018

- Published3 April 2018

- Published2 April 2018

- Published6 December 2013