Hopes and trauma in Mexico's migrant caravan

- Published

The caravan of Central American migrants arrived at the border town of Tijuana on Sunday

With many tears and much trepidation, the migrants prepared to set off on foot for the final short stage of their long journey to the US border.

The patience of the many children among their number was striking - although perhaps weariness was the real explanation.

One little girl stood quietly as a woman fixed the child's hair for an interview at the border which could determine the direction of her life.

A small boy in an oversized checked coat sucked his fingers and gazed around at the crowd as he sat on a man's shoulders.

A baby in a blue onesie and a little girl clutching a doll were also watching and waiting.

President Donald Trump says these families are putting the United States in peril. The migrants themselves insist they are fleeing danger, not bringing it with them.

'My country is beautiful'

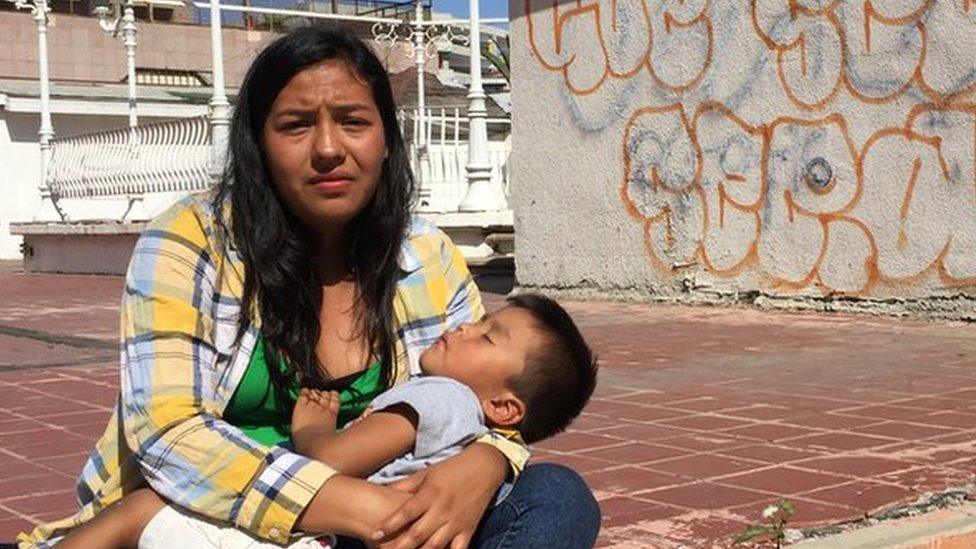

"Anna", 25, says she escaped Guatemala with her two-year-old son because she feared the boy's father was going to kill him.

"It was hard," she told me in Spanish. "We suffered on the way."

Migrants' route

She trembled as she spoke and tears ran down her face. Her little boy squirmed in her arms.

"Thank God we're here," she said. "Many people have supported us, have helped us - but it hurts to leave my country."

That is a common sentiment among the migrants. There is pride and patriotism here, tinged with regret and distress.

The blue and white stripes and stars of the Honduran flag were proudly on display and the national anthem of Honduras was proudly belted out.

"My country is beautiful," says Maritza Flores, 38, from El Salvador. "Beautiful places, but there is a lot of crime.

The migrant caravan Trump keeps referencing

"We leave our countries under threat. We leave behind our home, our relatives, our friends."

Ms Flores has been with the caravan since it set off from the southern tip of Mexico. She is travelling with her daughters, aged six and three.

"We had to bury some of our relatives before we left," she says, wiping a tear from her face.

Maritza Flores says her father was killed before she joined the caravan

After a long pause she adds: "My father was one of them. He was tortured."

"Many people think we left because we are criminals. We're not criminals - we're people living in fear in our countries. All we want is a place where our children can run free - where they're not afraid to go out to the shops."

This has been a journey beset with trauma. It has also been a long one, with the section through Mexico alone covering 2,000 miles (3,200km) from Tapachula on Mexico's southern border to Tijuana in the north.

"Anna" and her son had already travelled for three weeks before joining the caravan.

Months in detention

On a breezy Sunday afternoon some 200 of the migrants, including dozens of children, were driven in buses to the beach for a final rally before they decided whether or not to head for the busiest port of entry in the US and try to seek asylum.

This is not an easy decision, despite President Trump's assertion that the caravan members come to the border "because they know that once they get here they can walk right into our country".

This did not prove to be accurate.

Protesters gathered at both sides of the border fence on the Pacific coast

Nor is it the experience of many Central Americans seeking asylum. Most have their claims rejected. They often spend months in detention. They risk being deported to the country from which they are fleeing.

Parents are terrified of being separated from their children, although the US authorities say that only happens if a crime like child trafficking is suspected.

On the beach in Tijuana, where a metal fence separating California and Baja California runs into the foaming Pacific Ocean, protesters rallied on both sides on Sunday morning, determined to drown out the words of Donald Trump.

At the sea-washed gates of the world's most-powerful nation, the president's opponents said they wanted to see a United States built on compassion not hostility.

"Regretfully, this president doesn't have a heart," said one of the protesters, Christina Felipe Ramirez, 67.

"This president is the devil. He is a president descended from immigrants but he won't put his hand on his heart and understand that we immigrants also have the right to be here. Because we are more from here than he is, because he is not from this continent, we are from this continent."

An uncertain fate

By the time the rally was over and the migrants were preparing to take the final few steps to the border, word was seeping through that there was a problem.

There was a final rally before some migrants entered via the San Ysidro border crossing

The US authorities were arguing that they didn't have the room, didn't have the resources to handle the asylum claims.

Defiant, desperate, the migrants pushed on anyway. As they neared the frontier, the organisers of the caravan placed those they deemed the most vulnerable at the front of the queue: women, children and transgender people.

And then they were off - disappearing into the bright tunnels and white corridors of the San Ysidro border crossing, the busiest in the United States, their fate uncertain.

Something of a stalemate followed. The handful of migrants who had made it through the Mexican side of the border vanished from sight, the others were left to hunker down on the concrete.

And so this day in the caravan ended like so many others - with nothing more than American dreams.

- Published30 April 2018

- Published7 April 2018