On the battle lines over US abortion

- Published

Thousands of anti-abortion activists from around the US gather in Washington, DC in January for the annual "March for Life"

Organisations that offer or mention abortion to their patients will lose federal funding under new plans being drawn up by President Trump's team. One clinic and its foes consider what's next in America's polarised abortion debate.

Ten women walk along a busy, fluorescent-lit corridor. Undressed from the waist down, they wear big white sheets knotted over their hips, as they make their way to the "relaxation room", a windowless space, equipped with large sofas and a TV. There they wait for their turn to have an abortion.

This is Hope Medical Group, a small abortion clinic in Shreveport, Louisiana, serving a 200-mile radius through rural Louisiana, neighbouring Texas, Arkansas and Mississippi.

Appointments fill up quickly for mainly first-trimester abortions. Thirty women are scheduled to come in today - and only one fails to show up.

"You think this is busy? Wait to see what Saturdays are like," says Kathaleen Pittman, the clinic's administrator.

Pittman says she has trouble sleeping at night, but its not because of a guilty conscience.

"Hell no, it's because I'm worried about how we can take care of patients with all these new rules they're trying to impose," the 60-year-old Louisiana native says.

When Pittman joined Hope in the 1980s, things were different.

Back then there were 11 abortion providers across the state. Now there are three to serve 10,000 women, Pittman estimates.

"Pressure on us is getting worse year after year," Pittman says from this Louisiana abortion clinic

Nationwide the number of clinics has plunged in the last decade. Seven states are now down to just one.

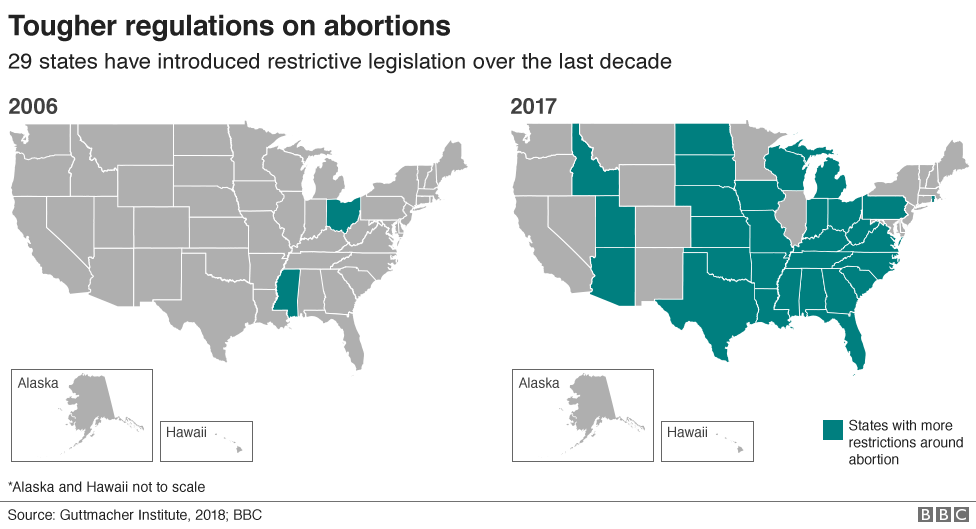

And with newly approved regulations, the pressure for medical providers is mounting. In 2017, 19 states passed 63 abortion restrictions. Twenty-nine states now have enough restrictions to be considered hostile to abortion rights by the research group Guttmacher Institute.

The issue is high on the political agenda of the federal government too. In his first year as president, Donald Trump appointed a conservative Supreme Court justice and cut federal aid to international groups that advise on pregnancy termination.

And anti-abortion activists have also become louder since the 2016 election.

"Let me tell you, things aren't getting any better," Pittman says.

Lucy

Lucy travelled for three hours to get to the clinic. Eight weeks pregnant, she took a day off from work as a store cashier in a town she prefers not to name, and asked a friend to drive her.

At 21, she is on her own with a 10-month-old baby.

Her daughter, Bradley, will be one in October and Lucy doesn't want a newborn just a few months later.

"I want to go back to school and with two kids it ain't working," she says.

She will go ahead with the abortion, she says, regardless of the father's wishes.

"It is the same guy from my first baby and he doesn't really take care of her, so I wouldn't expect him to take care of a second."

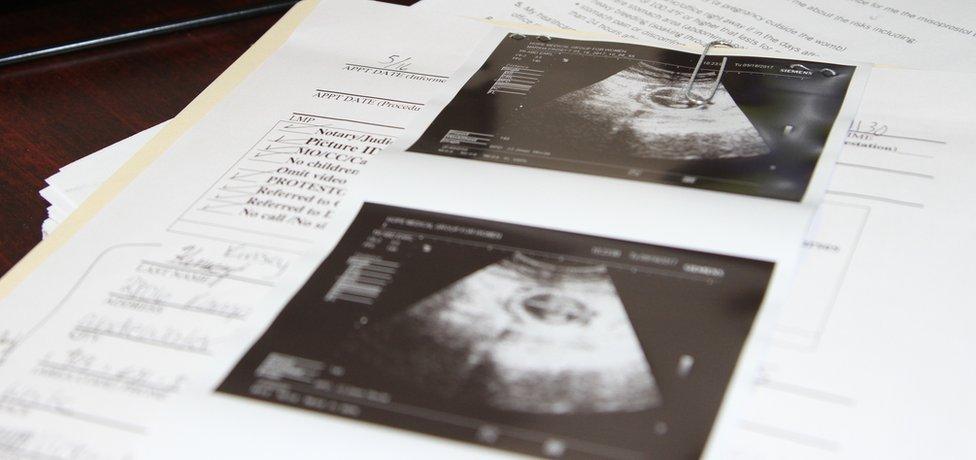

By law, patients have to have a ultrasound scan as well as a counselling session before consenting to the surgical procedure

Lucy begins her visit with a counselling session made mandatory by state legislation. It is a one-to-one conversation with one the clinic's advisers, in which the patient goes through a long consent form.

Delia, the counsellor in charge, explains the potential risks outlined in the law in well-rehearsed detail: infection, clots and haemorrhages, perforation of the uterus wall. The list goes on.

Lucy listens, not a hint of hesitation on her face. She explains she may need financial help, as her paycheque is around $525, less than the $550 fee for the procedure. Louisiana only covers the cost of abortion under Medicaid for cases of rape, incest or life endangerment.

A contribution from clinic's private funds brings the bill down to $400. She can get an appointment five days later.

"Tuesday? That's fine," Lucy nods. "Wednesday's my day off work so I'll get some rest after."

A 45-year divide

Abortion has been legal in the US since the 1973 landmark Supreme Court ruling Roe v Wade.

It has been a contentious issue ever since, one that splits deeply along ideological and religious lines.

Activism in favour of abortion rights has also grown during the Trump era

A 2017 study from Pew Research Center revealed that "the partisan divide on abortion remains far more polarised" than it was two decades ago.

And the last presidential race was no exception.

During the campaign, Trump promised he would take action to "advance the rights of unborn children and their mothers" but his choice of Mike Pence, one of the most active anti-abortion politicians in the US, as running mate was a bold stance in the eyes of his conservative supporters.

Vice President Pence addressed a rally protesting abortion just days after Trump took office

The results for the Trump administration have been mixed. Legislation to effectively defund Planned Parenthood, the largest network of women's clinics in the US, failed to get through Congress.

But in January this year, Trump issued a directive making it easier for states to exclude Planned Parenthood facilities from government-funded programmes, and another one allowing healthcare workers to refuse to perform an abortion based on "religious or moral" objections.

Safety and surveillance

At Hope's front desk, a receptionist buzzes patients through a reinforced door, while she monitors the clinic's perimeter on an overhead screen displaying footage from 15 CCTV cameras.

Trespassing, burglary and vandalism have shown a marked uptick in clinics nationwide since the last presidential election campaign kicked off.

15 CCTV cameras guard Hope

Reports of intimidation tactics and threats have escalated, according to the National Abortion Federation (NAF), a professional association for abortion doctors that has been compiling statistics since 1977.

Threats of violence or death almost doubled at clinics in 2017 while trespassing cases more than tripled from a year earlier,

The reported number of picketing incidents, for instance, was more than 78,000 in 2017 - an all-time high since NAF began keeping track.

The National Clinic Violence Survey showed a spike too, with nearly half of all providers reporting some form of violence in 2016, a 6.2% increase from 2014.

It comes as no surprise that Hope's two medical practitioners ask me to protect their anonymity.

"Abortion foes destroy your ability to make a living," says a gynaecologist who has been working here for 36 years.

He performs abortions two days a week but also runs a private practice in town. Anti-abortion activists left flyers all around his practice, telling neighbours he "killed babies" and threatening to "take him to Jesus". He had to get local police to patrol his house.

"The pressure has been such that other physicians decided to stop doing abortions," he says.

He is not planning on quitting. "This service is needed, especially in a poor, historically anti-choice state like ours."

Praying warriors

"The abortion debate is becoming prominent because there is no more important issue in life than life itself," says Chris Davis, a spokesman for the pro-life community in Shreveport.

He meets me outside Bossier Medical Suite, a 15-minute drive north of Hope. This was the most recent Louisiana clinic to close down, in April 2017.

It's a terracotta-bricked, unassuming building in an open commercial piazza, surrounded by an empty parking lot.

"This was usually packed with cars," Davis says. "We prayed every day outside this facility and we feel that God has answered those prayers in a very big way."

Chris Davis is part of the Praying Warriors, a group partook in "sidewalk activism" outside the Bossier clinic, now closed

Davis, a father of three who defines himself as a "strong Christian", takes part in a series of praying vigils held on the sidewalks outside clinics.

They call themselves the Praying Warriors. They camp outside the perimeter and try to get the patients' attention as they walk in. Trespassing regulations prevent them from stepping onto the clinics' grounds.

"What we focus on is not necessarily overturning Roe v Wade overnight," Davis says.

"With every woman that changes her mind after talking to us or seeing us pray, Roe v Wade is overturned in a grassroots effort. One woman, one baby at a time".

Carol Harris hands out flyers with photos of a foetus at different stages of development and a testimony of a regretful mother after a termination

Catalya

Catalya avoids all contact with the protesters outside Hope when she rushes into the clinic.

Dressed in sweatpants, flip-flops and a well-worn red shirt, the 22-year-old drove two hours from Mount Pleasant, Texas, to have an abortion. It will be her second.

"With my boyfriend we had already agreed that we could not afford to have a child right now. It was either abortion or adoption... and I just can't imagine giving my child away".

The couple already has a one-year-old.

The waiting room in Hope is full - and mostly silent- at all times

"I work evenings and the father works mornings," she says. "But we are being offered less work lately, it's been hard to get by."

Together they make around $800 a month from 10-hour shifts in a food processing plant.

"And we are never together with Andre. That's already bad, how can we put another child through the same?"

If she earned more, Catalya says, she'd "definitely" keep the pregnancy.

Hers is a well-known tale for the clinic's workers. Financial constraints, they say, is the main reason given by women here - overwhelmingly African-American, lacking educational opportunities and access to contraception - for terminating their pregnancies.

Catalya tells me she's having second thoughts, but doesn't share them with the counsellor.

She thinks it's a personal matter that would be best decided at home - she still has to convince her boyfriend.

The ultrasound scan confirms Catalya is five weeks pregnant. She refuses to look at the screen during the examination.

"There's no heartbeat 'cause it's way too early, but the fact it's a baby bothers me," she tells me once the scan is over.

She burst into tears. "It is not the baby's fault… it's nobody's fault."

She pauses, wipes off her cheeks and looks up, recomposed. "We simply cannot afford it, I'm sorry."

State battlegrounds

Making abortion illegal again in the US would be a complex matter. Only the Supreme Court or a constitutional amendment would have the power to overturn Roe v Wade.

So in recent years, conservatives have sought to change rules at state level, rather than seek an outright ban.

In the first six months of Trump's time in office, 431 provisions restricting abortion access were introduced in state capitols across the country, as monitored by the Guttmacher Institute.

Louisiana has one of the most controversial bills of the lot - a ban on abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy, instead of the current 20-week limit, passed the state Senate in April.

If it is signed into law, it will become the second strictest time limit nationwide, on a par with Mississippi and only behind Iowa.

Critics deem these laws unconstitutional.

Campaigns like Trust Women work to keep clinics open in underserved communities, in the face of tightening regulations

"Restrictions, restrictions," sighs Kathaleen Pittman. "Probably the first one that affected us dramatically was the 24-hour waiting period."

Since 1995, all women must meet with a doctor at least 24 hours prior to getting an abortion, making two separate appointments. Louisiana wants to extend it to 72 hours, but the law has been blocked with a lawsuit filed by the Center for Reproductive Rights.

Tripling the current 24-hour rule will put Louisiana on par with just five other states for the nation's longest mandatory waiting time.

"The double visit system is hard enough as it is." says Stephannie Chaffee, who has been working with Pittman for 10 years.

"Lots of women take a day off work and lose wages, many have to find somebody who would babysit for them. And they have to do that twice".

"They travel distances, sometimes they need to pay for lodging. Imposing a 72-hour waiting period would make the process even more costly," Chaffee says.

“95% of the women that come here have thought long and hard before making the phone call," says Chafee. "So the 24-hour mandatory wait rarely makes them change their minds."

Battle lines drawn

A tropical storm rages over Shreveport on Saturday, the day the clinic is at its busiest.

There are 50 abortions scheduled, twice as many as on weekdays. The heavy rain does not deter patients from showing up.

Seven raised-legs beds allow patients to rest after the surgical procedure

Outside, there is also a sudden flurry of activity.

A group of anti-abortion activists have gathered on the sidewalks, battling the rain with extra-large umbrellas.

There are 32 of them, of all ages, engaged in a low-paced pilgrimage as they say prayers and hold crosses, bibles and rosaries.

A trailer van drives by, slowly and unceasingly, displaying a giant billboard with an image of a foetus and the words: "Will you protect me?"

"We are not here to attack doctors, we are here to promote life right where life is being destroyed," says Richard Sonnier, who has knelt down, his arms raised to the sky.

He tells me he paid for an ex-girlfriend's abortion some 40 years ago and has regretted it ever since.

"This is our time. Changes in the law will lead to a lot of clinic closures," says Charles, a man holding an imposing wooden crucifix. "It's about time this city becomes abortion-free".

"This is a business, there is a lot of money in the abortion business and it has to stop," says Charles

Richard Sonnier said he became a pro-life activist after paying for a former girlfriend's abortion

Days earlier Chris Davis told me "this is a culture war".

If there's such war, then this Shreveport corner is a battleground, the two antagonising camps strikingly visible.

For almost every anti-abortion activist, there's a clinic volunteer.

As much as having Republicans in the White House has emboldened anti-abortion groups, it has also encouraged larger numbers of reproductive rights supporters to take action.

The number of supporters of abortion rights taking it to the streets across the country has also grown during the Trump administration

Dressed in fluorescent vests, chaperones are here to escort cars into the parking lot.

"These women have a lot in their minds already, seeing a friendly face here might help them," says 69-year-old Ron Thurston, who is one of Hope's regulars.

"The protestors are addressing the wrong people," adds Christian, 23. "This battle comes down to legislation, so I don't get why they think they'll get things their way by shouting at women in distress".

Inside the clinic, everyone is keeping an eye on the CCTV screens.

"Do we feel intimidated? Hell no," says Pittman, adding she is "too busy to be angry". There's a crowded waiting room of patients.

Protests outside Hope attract an ever-growing number of anti-abortion demonstrators

'I feel some regret'

When I called Lucy a week after her procedure at Hope, she has recovered and is back to her cashier job.

But things for her did not go exactly as planned.

"It was bad, really painful even though they said it wouldn't be," she says.

She wouldn't do it again - and not just because of the physical pain.

"I feel… sort of regret," she says. "I talked to the father, I would have kept the baby in hindsight... I didn't think I was going regret it but the truth is I do".

Catalya also went ahead with the abortion.

Her partner drove her to the clinic and waited the four hours. On the way back they stopped for ice cream, her favourite treat.

"Of course it is hard, it's not a decision made lightly", she says. "But it was best for our family."

"I'm really relieved that I had the opportunity, with my rights as a woman and all, to come and get an abortion."

Some names have been changed at the request of the interviewees to protect their privacy.