Women's Equal Rights Amendment sees first hearing in 36 years

- Published

Women advocating for the ERA on Capitol Hill in 2018

The Equal Rights Amendment is back on Capitol Hill - 36 years since its last hearing and nearly a century since the amendment to guarantee equal rights to women was first introduced in Congress.

On Tuesday lawmakers in the House Judiciary Committee's subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Civil Liberties heard from witnesses - including actor and women's rights advocate Patricia Arquette - about why, years on, the amendment is still worth considering.

Democratic Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney of New York in January again sponsored a resolution, external to restart the ratification process needed to add the amendment to the US constitution.

The provision would not change any laws, but seeks to formally give women the same citizenship status as men.

While 76% of constitutions around the world in some way guarantee women's equality, external, the US constitution, technically, does not.

Last June, the state of Illinois voted in favour of the amendment, becoming the 37th state to do so.

In theory, only one more state must ratify the amendment to obtain the majority needed to amend America's founding charter.

"With issues of equality at the forefront of today's conversations; with the #MeToo and Time's Up movements, with the Women's Marches and more women than ever before running for and being elected to office - we have an extraordinary responsibility and opportunity to seize this moment," Ms Maloney said when the hearing was announced earlier this month, external.

It's easy to see why the ERA is back on legislators' agenda in this political climate, but why has it taken so long?

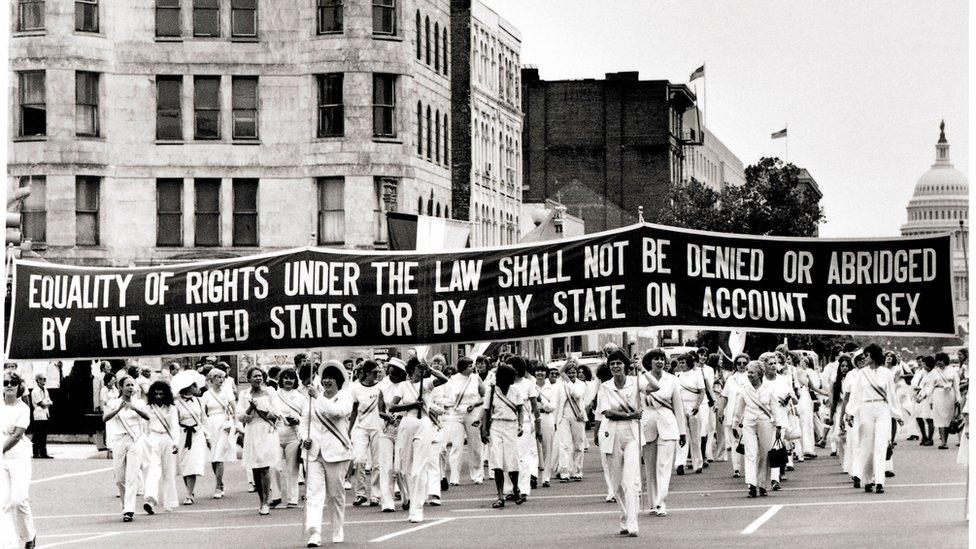

Women supporting the ERA carry a banner down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington DC on 26 August 1977

What is the Equal Rights Amendment?

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) states: "Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex."

Congress first introduced the ERA in 1923, but the campaign for ratification took off in the 1960s during the civil rights movement.

In 1972, Congress passed the amendment and sent it to the states for approval. Thirty-eight states must ratify an amendment before it is added to the Constitution.

According to Gallup Polls from 1975-81, the majority of Americans - men and women - were in favour of the amendment. In the 1970s, only an average of 27% of those polled opposed it.

Senators who opposed the ERA persuaded Congress to set a seven-year deadline for states to pass the amendment. Congress even extended that deadline an additional three years in 1978.

By 1977, 35 states had ratified the ERA - and then the movement stalled until 2017.

In 1976, Phyllis Schlafly led anti-ERA protesters in Washington DC

So why did it fail?

Many historians attribute the failure to one conservative woman: Phyllis Schlafly.

Mrs Schlafly was a lawyer and housewife from Illinois who founded the Stop ERA group.

Her campaigning became one of the first grassroots conservative movements in the US.

"Women's libbers are promoting free sex instead of the 'slavery of marriage'," Mrs Schlafly wrote in a 1974 issue of Society Magazine.

"They are promoting Federal 'day-care centres' for babies instead of homes... abortions instead of families.

"Let's not permit this tiny minority to degrade the role that most women prefer."

Mrs Schlafly capitalised on many of the same fears that plagued the suffrage movement: that the ERA would promote abortions and homosexuality, send women into military combat and deny a woman's right to be supported by her husband.

"Those fears at the time were greatly exaggerated or untrue," Jane Mansbridge, political science professor at Harvard University, told the BBC.

"The controversies were all spurred by what I and many lawyers believe to be misinterpretations of the ERA."

Mrs Schlafly motivated conservative women across the country to rally behind "the rights of the wife".

Marjorie Spruill, professor emerita of history at the University of South Carolina, said Mrs Schlafly's campaign used religion to form "an effective coalition" against the ERA.

"Traditionally Catholics, evangelical and fundamentalist Protestants, and Mormons distrusted and were hostile to one another, but they shared a mutual fear and disdain regarding feminism," Prof Spruill told the BBC.

"Conservatives pointed to the many successes of the feminist movement to say that women can achieve equal rights without a questionable, potentially dangerous constitutional amendment."

Women march in Washington DC after Trump's inauguration

Why are we talking about it now?

The ERA has been before every session of Congress since 1982, but the 2016 presidential election and the #MeToo movement has moved the ERA back into the public eye.

After Illinois' vote, the National Organization for Women president, Toni Van Pelt, told NPR, external: "The #MeToo movement has underscored the importance of strong legal protections for women's rights."

And #MeToo advocate Alyssa Milano is also present at Tuesday's hearing, highlighting the movement's impact.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Alyssa Milano speaks with ERA activists outside the hearing room on 30 April

Did Illinois' ratification last year actually mean anything?

"Given that Illinois was Schlafly's home state, it is a big symbolic victory," Prof Spruill said.

It was also the only non-Southern, non-Mormon state not to ratify in the first round.

Only 13 states have not ratified the ERA as of April 2019 - and only one more must do so to approve the measure, in theory.

But the 1982 deadline from Congress has long since passed.

So could the ERA make it on to the constitution?

Susan Bloch, professor of constitutional law at Georgetown University, said it will all come down to timing.

"That'll be the question - when they added the time limit, was that legitimate? If it was, then these are clearly too late," she told the BBC.

Those opposing the ERA maintain that the deadline has passed, so the entire ratification process will need to start over for the amendment to be legitimately added.

Supporters of the amendment point to the fact that the 27th amendment - which governs Congress members' salaries - passed after more than 100 years, so time should not be an issue.

They also say that since the constitution does not mandate time limits for amendments, the ERA is still valid.

"When the constitution was written, they didn't contemplate these [amendment proposals] dragging on for hundreds of years," Prof Bloch said.

"I don't think anyone contemplated this crazy scenario. The fact that this amendment has been hanging around so long, and some of the ratifications are new and some are old and some are rescinded or modified weakens the argument that this is a contemporaneous expression of what the people want the constitution to say."

The states who rescinded their ratifications pose another problem. The legality of the recessions has yet to be debated in court.

Pro-ERA protesters marched through downtown St Louis in 1970

But do we still need an ERA?

To Prof Spruill, the answer is a resounding yes.

"Having the ERA would make it far more difficult for conservatives to roll back the gains of the women's rights movement," she said.

"It would give women's rights more protection [and] raise the level of scrutiny to gender issues to the level of racial and religious issues."

Prof Spruill acknowledged that much of what conservatives in the 1970s feared has already come to pass, including women joining the military in combat roles, gender neutral bathrooms, the legalisation of gay marriage and abortion protections.

Constitutional lawyer Prof Bloch told the BBC she didn't feel the amendment was entirely necessary given current legal protections for equality.

"It wouldn't hurt if it were legitimately ratified," Prof Bloch added. "If it gets ratified, it is just another arrow in the quiver of legal arguments."

For Prof Mansbridge, the US constitution needs the ERA - not to alter laws, but to maintain principles.

"A good analogy is the first amendment to the US constitution.

"The framers did not have in mind a specific way that this amendment would change the existing law.

"They just thought it was a good idea to have that principle in the constitution."

The equality of women, she argued, is just as important.

- Published12 May 2018

- Published21 January 2018

- Published16 May 2018