Locked up in Canada for eight months 'over name mix-up'

- Published

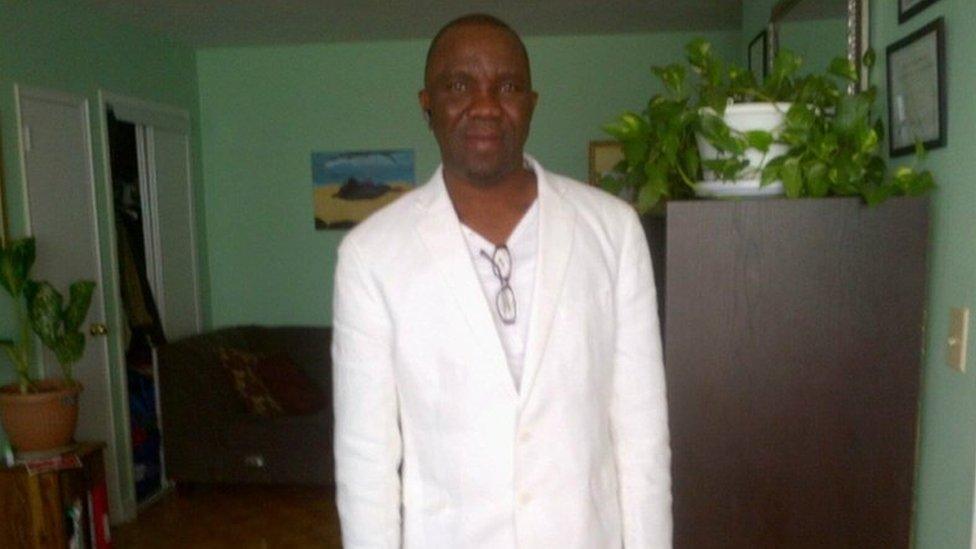

A Canadian citizen was held by immigration authorities for eight months in a top-security prison when he was mistaken for a refugee with a different name. Now, he's suing the Canadian government for C$10m ($7.6m, £5.7m).

When 47-year-old Olajide Ogunye, born in Nigeria, woke up on the morning of 1 June 2016, he found his home in Toronto surrounded by Canada Border Service agents.

"It took me five minutes just to get to my car," he told the BBC.

Before he could drive off, an agent challenged him.

Ogunye showed them several forms of ID, including his Canadian citizenship documents and a provincial health card. The agents told him they would "sort this out", and drove him to their office where they fingerprinted him.

They said his fingerprints matched those of Oluwafemi Kayode Johnson, a failed refugee claimant who had been deported from Canada in the 1990s, whom the immigration authorities believed had illegally returned to the country.

They booked Ogunye into Maplehurst Correctional Complex, a maximum-security prison for dangerous offenders.

"I wasn't expecting something like that to me as a Canadian citizen," Ogunye says.

For the next 248 days, Ogunye would be incarcerated - first in Maplehurst and then in Central East Correctional Centre, another maximum-security prison - while CBSA investigated his case.

Now that he is a free man, Ogunye is suing the government for C$10m for wrongful arrest and negligent investigation.

CBSA spokesman Barre Campbell told the BBC the agency is "reviewing the matter" and that "it would be inappropriate" to comment further.

His lawyer, Adam Hummel, says that the CBSA's investigation was marked by delays and procedural irregularities that lengthened Ogunye's stay in prison and took a toll on his mental and physical health.

"For them to keep someone in jail for eight months... it is not really a good thing. I hope they don't do this to somebody else and that is one of the reasons why I'm bringing this to court," Ogunye says.

Hummel also says the CBSA has never produced the fingerprint sample used to identify Ogunye as Johnson.

Ogunye moved to Canada from Nigeria with his parents in 1990, and obtained citizenship at 26 years old in 1996. He has several siblings in Canada, as well as two daughters, both born in Canada.

At one point, his lawyer arranged for him to be granted bail, if two bondsmen would swear to his identity. The bondsmen swore that he was indeed Olajide Ogunye.

But according to the statement of claim, the CBSA would not accept any proof that did not corroborate their belief that he was Johnson because "fingerprints don't lie".

In prison, Ogunye says he was assaulted by fellow inmates and fell into a deep depression and was placed on suicide watch.

"I'm crying like 24/7 in jail," he says.

This is not the first time Canada's immigration detention system has fallen under scrutiny.

A 2017 investigation by the Toronto Star found that about 114 immigration detainees were being held in jails and prisons for three months or more while the immigration and refugee board reviewed their cases. Less than 1% of detainees who have been incarcerated for six months or more are released, the investigation found., external

Inside America's $2bn immigrant detention industry

Ogunye was one of the lucky ones.

Six months after his arrest, CBSA interviewed his brother and sister, according to the statement of claim.

They confirmed he was their brother Ogunye, not Johnson and in February 2017 he was released.

In his release report, the investigating officer wrote that "the person in custody may be Olajide Obabukunola Ogunye", the statement of claim says.

Since leaving prison, Ogunye says he has lost his job at a hair salon, which he held for 17 years, and his relationship with his daughters has deteriorated.

Matters may have been complicated by Ogunye's own past criminal record. According to Hummel, CBSA agents told his former lawyer that they did not believe Ogunye because of charges related to credit-card fraud and impersonation back in the 1990s.

But his current lawyer says his past is irrelevant.

"The minute he showed him he was a Canadian citizen, everything that they were doing that dealt with immigration was unlawful," Hummel says.

- Published8 June 2018

- Published13 March 2018