Supreme Court: Why a fight over US abortion law now looms

- Published

Fear or opportunity? Liberals and conservatives on what's next for the US Supreme Court

Anthony Kennedy was a swing vote on the US Supreme Court, albeit one that frequently tilted to the right. Replacing him with a solidly conservative justice, however, could have a significant impact on US jurisprudence - and politics - for decades to come.

Here's a look at some of the most consequential issues.

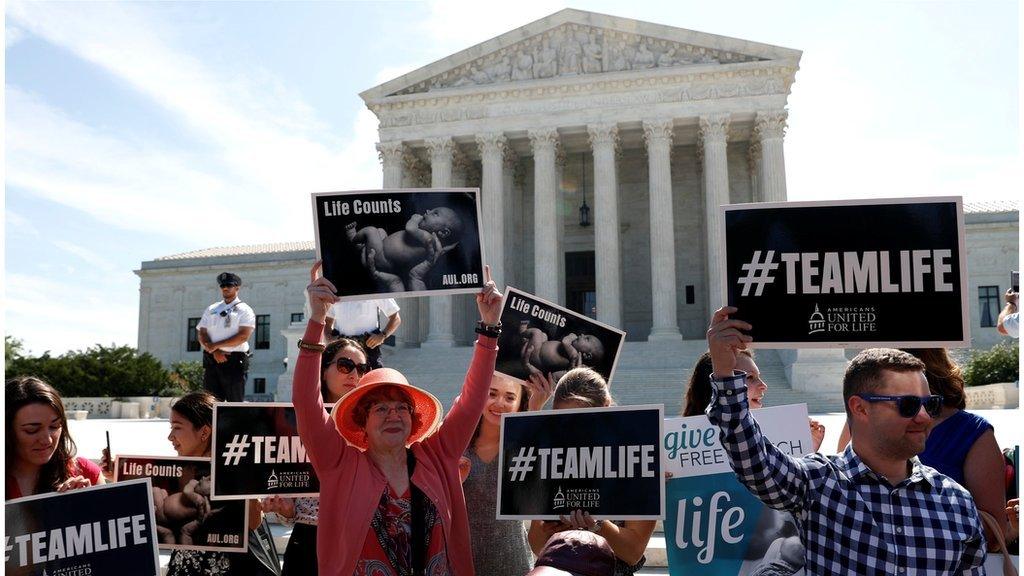

Abortion

Shortly after Mr Kennedy announced his retirement, Supreme Court analyst Jeffrey Toobin tweeted that "abortion will be illegal in 20 states in 18 months" - an indication that he believes Mr Trump's nominee will join a majority in reversing Roe v Wade, the 1973 decision legalising abortion throughout the US.

Anti-abortion advocates have been trying to scale back the broad constitutional guarantees of the Roe decision in the decades since, and now - without Mr Kennedy on the court - they could be poised for a breakthrough.

Back in 1992, when Mr Kennedy was just a junior justice, the court considered a series of Pennsylvania restrictions on abortion rights in a case, Planned Parenthood v Casey, that could have drastically curtailed what had been established as a constitutional right to abortion.

Mr Kennedy reportedly initially sided with the more conservative justices but eventually co-wrote a three-justice plurality that upheld the "essential holding" of the landmark Roe decision legalising first-trimester abortions throughout the US.

Since then, Mr Kennedy has frequently sided with abortion rights advocates in the court, most recently last year, when he joined the court's four liberal justices to strike down a Texas law stringently regulating abortion clinics and the doctors who perform the procedure.

The Pink House: The last abortion clinic in Mississippi

It may not be long before the Court considers the next big abortion case, as there is already an Iowa law prohibiting the procedure after a foetal heartbeat is detected - usually around six weeks of pregnancy. The measure is currently on hold pending a legal challenge from abortion rights groups.

At the very least, a court without Mr Kennedy could uphold the constitutionality of state-level regulations that make abortion effectively - if not legally - unavailable in a number of states where only a handful of clinics currently operate at the moment.

Gay rights

The White House was lit up in rainbow colours after the Supreme Court ruled gay marriage constitutional in June, 2015

Mr Kennedy may be most remembered for his support for cases involving gay rights. He sided with the majority in a 1996 decision striking down a Colorado measure banning city-level anti-gay discrimination ordinances. In 2003, he authored the decision holding that a Texas law that made gay and lesbian sex illegal was unconstitutional.

His most famous opinion, however, surely is the 2015 ruling that legalised gay marriage across the US. In Obergfell v Hodges, Mr Kennedy wrote that marriage "allows two people to find life that could not be found alone" and that the Constitution grants gay couples right to "equal dignity in the eyes of the law".

The Court's vote was 5 to 4, the narrowest of margins, and while a newly constituted conservative majority on the court may follow precedent and not directly reverse this decision, it could take steps to allow individuals and corporations greater freedom to deny civil rights protections and accommodations to gay persons and married couples by citing religious beliefs.

The court also was poised to consider the constitutionality of school bathroom bans for transgender students before the Trump administration reversed an Obama-era guidance prohibiting such bans. The case is back at the lower-court level and could end up in the next few years on the docket of a Supreme Court that looks very different from the one that would have ruled on the matter this term.

Death penalty

Capital punishment has been allowed in the US since a Supreme Court decision upholding the constitutionality of the practice in 1976. Mr Kennedy has not questioned that precedent, but he has repeatedly sided with justices who have chipped away at who can be executed and under what circumstances.

In 2005 he wrote the majority opinion ruling that capital punishment was an unconstitutional punishment for crimes committed by those under the age of 18. He joined a 2002 opinion prohibiting the execution of those with intellectual disabilities and authored a 2014 majority opinion limiting a state's ability to decide who is and isn't mentally capable.

There has been some speculation that the Supreme Court could be steadily progressing to a point where it could rule that capital punishment in all cases constitutes "cruel and unusual punishment" prohibited by the Eighth Amendment to the US Constitution.

There is a good chance that whoever Mr Trump picks to replace Mr Kennedy will bring this trend to a halt.

Affirmative action

The ability of public colleges and universities to consider race and ethnicity in an attempt to create a diverse student body has been on shaky grounds for years.

Mr Kennedy has opposed any type of school admissions process that gives individuals an advantage in admissions based solely on their race. In 2016, however, he authored a majority opinion, again by one vote, that upheld a University of Texas practice of weighing an applicant's race among a number of factors in a "holistic review" of a prospective student's enrolment application.

In the wake of a US Supreme Court decision over Michigan's affirmative action policies, the BBC takes a look at American public opinion on the issue.

It was an opinion that walked a fine legal line, allowing public universities to craft policies that created a more diverse student body while avoiding quotas and other direct actions. That's a line the other conservative justices have shown no interest in observing.

With one more reliable vote in their number, Mr Kennedy's measured "maybe" could be replaced by a firm "no".

A partisan firestorm

The new Supreme Court vacancy is certain to throw petrol on the smouldering flames of anger and resentment that have come to define US politics in the Trump era.

Liberal activists are girding for all-out war, although their ability to block the Republican-controlled Senate's ability to confirm the president's nominee is limited.

Mid-term congressional elections are less than five months away, and the coming confirmation fight is sure to figure prominently in the campaigns.

"We have a very excellent list... of tremendous people"

Republicans running against Senate Democratic incumbents in Trump-friendly states like West Virginia, Indiana and North Dakota are sure to highlight any moves their opponents make to block the president's choice.

Meanwhile, Democrats targeting at-risk Republicans in House of Representatives races could capitalise on increased engagement and energy from liberal voters who view abortion and gay rights at new risk.

In 2016 the open court seat ended up helping Mr Trump by spurring evangelical voters and cultural conservatives to stick by their candidate despite his various controversies and missteps. At the time, Republicans were on the defensive - facing the prospect of conservative Justice Antonin Scalia being replaced by a liberal jurist.

Now Republicans are on the attack, with the opportunity to cement a conservative court for a generation. Democrats may not be able to do anything to stop it at this point, but flocking to the polls in November may give them some measure of comfort - or revenge.