My life trapped in an American city

- Published

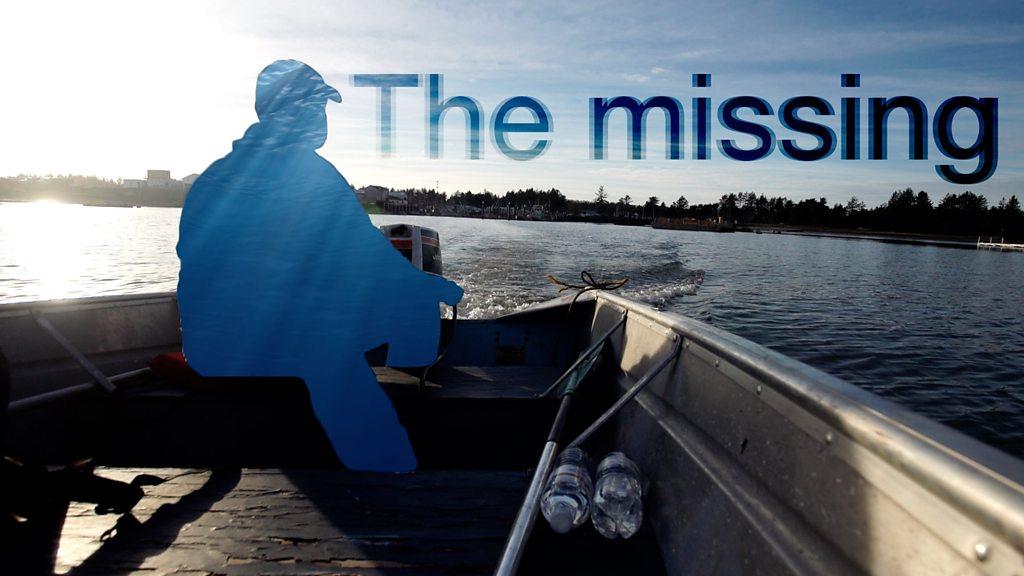

A student who came to the US from Mexico illegally as a child says she cannot leave her city because it is surrounded by checkpoints and she fears being deported. Her sisters and parents live hundreds of miles away. This is her story.

My family and I migrated to Phoenix, Arizona, when I was eight years old. I'm now 22 and a student of engineering at the University of Texas at El Paso.

I'm not a criminal yet in a way I'm treated like one.

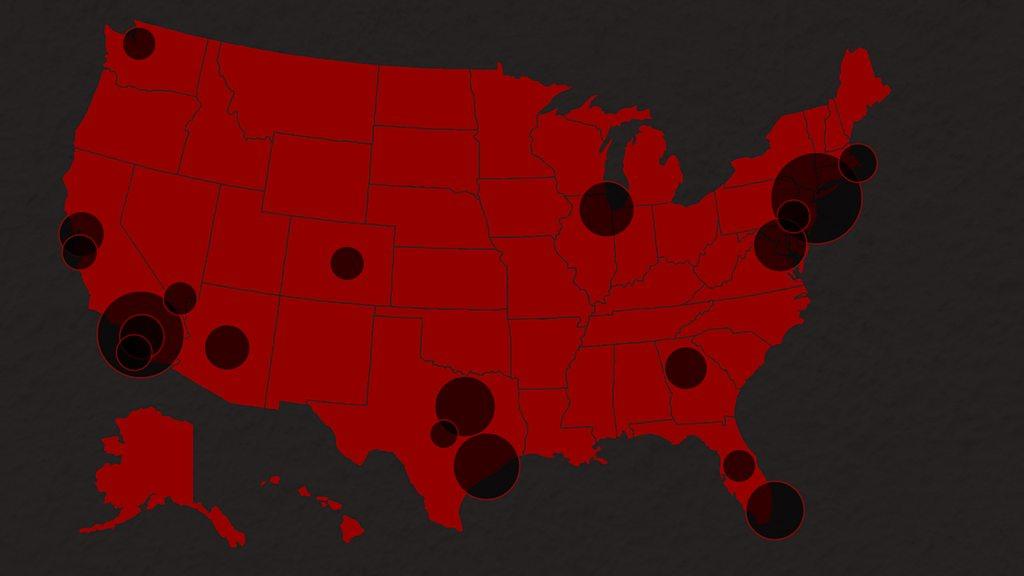

El Paso has checkpoints around it where immigration officers ask for your documents, documents I obviously don't have. I can't leave the city or I risk deportation. Fortunately, my parents became US residents two years ago but, unfortunately, this isn't the case for my sisters, aged 25 and 18, and me.

When they got their papers they moved back to Phoenix in search of more job opportunities after four years of living here. But I risked putting my college education in jeopardy and getting deported if I crossed the checkpoint and was asked for my documents.

My parents passed fine and it was a coincidence that my younger sister, then 16, had a school trip to New Mexico. You have to cross a checkpoint on the way there. But as immigration doesn't check school buses looking for undocumented migrants, she was able to travel without any problems. On the way back, my parents went there to pick her up so it was all perfect.

But as I'm stuck in El Paso, I'm unable to visit my family.

My parents visit me once every three or four months - because of work and other things they can't be here more often. But since they all moved I haven't seen my youngest sister. Her high school graduation was last month and I was unable to go even though everyone in the family was there. And I know neither one of my sisters will be able to attend mine.

This is without mentioning all the birthdays and holidays that have passed without us being together. The last time I saw my other sister was three years ago. (I have a third sister, 10 years older than me, who is an American citizen and lives in California. My parents were able to become residents after she submitted an application for them.)

I'm happy for one part that my sisters are in Phoenix because there are no checkpoints around there and they're able to go to California every now and then. I try not to complain since I'm the first of my parents' children to go to college. I feel very lucky. On the other hand, there are days when I'm just tired of it.

I feel like I don't have rights.

Before my parents left, they warned me to not leave the house with my hair too messy or without make-up given that this is the typical stereotype Border Patrol agents look to target immigrants. And given that I live in a border city, the city is full of agents. I don't even risk jaywalking, I always walk the longer way to reach a traffic light to properly cross the street.

It was an idea from my dad for me to always carry $100. Because if I happen to be deported on the spot I'll have some money to pay for a hotel in Ciudad Juarez and be safe.

They also told me to not trust anyone with my situation given that I could be blackmailed. I live with three other students, one of them for two years and not even she knows. Whenever my colleagues are planning trips outside El Paso I first agree and then give an excuse because I can't pass a checkpoint.

When they ask me "Why aren't you working? or "Why don't you drive?" I have to make them believe that I'm lazy. So they just stop asking. The truth is I'm unable to work or get a driving licence.

As soon as we crossed the border I had to assimilate myself. I learned English and as I was learning it as a child, our teachers would straight out say "Stop speaking Spanish. You're in America now". A few months later I would win spelling bees - compete against white people who only spoke English - and still win.

After the 2008 recession my dad, a civil engineer, couldn't find a job in Phoenix and we lost the house we had. So we had to go back to Mexico.

I had such a terrible time, it was probably the worst of my life. I was so Americanised that I didn't fit in. That's what they ask you to do to be accepted in the American culture. I had lost my Mexican identity. We were there for a year and a half before we came back.

I know so much history about this country, more than average US nationals, and I have so much respect for it seeing as I get myself involved in politics to help improve this country's current state. I involve myself more than citizens, people who should worry more about this nation given that it really is theirs.

But it's scary. For instance, in the Women's March in January I had to protect myself - I didn't pose in many pictures and covered my face with posters. I know it's risky going to these protests because of my situation. I want to help, but I can't.

It's difficult to dream in a country that, regardless of everything I've done, which is what most immigrants do, doesn't welcome you even if you've seen it as home for most of your life.

I understand that they have the right to choose to whom they grant citizenship. I just wish they would give me some sort of help. I've given up part of my culture, my roots, to be accepted here. I've already given some of me.

Why can't this country give something back?

Since I'm not a citizen I don't qualify for the financial aid that the government gives to students or for most scholarships. I looked at almost everything. My dad pays for my college, my apartment and bills all by himself.

Three semesters from now, when I graduate, I may still be deported. And I may never see my sisters again until they can get papers, which by the looks of it will probably be in 12 more years.

I know I was born in Mexico but I no longer live there; I'm too different from the people there, I can't just start over in Mexico.

Therefore, I've had to prepare myself in case I'm deported. So I've been planning to move to Germany if it happens. I've been learning German without my family knowing because I know if my parents find out now they'll try to talk me out of it.

So the plan once I graduate is that, if I feel that it's very possible that they'll deport me, I'll cross the border to Mexico. At least I'll have my degree and I won't have a deportation on my file if I have to go back to the US. Then maybe Germany, who knows.

I'm well aware that my situation is not the worst one. There are plenty of Central and South Americans that have a terrible time crossing Mexico to get to the US, but that doesn't mean that I'm not separated from my family or that I don't sometimes start the day crying from the frustration of being apart from them for basically no reason.

You can't deny that this has affected me. This shouldn't be happening.

Illustrations by Hannah Lazarte

Interview by Hugo Bachega

Take part in Ask America

This story emerged when we asked our readers if they had been affected by an immigration-related separation.

Now we're asking you: What's the untold story in your community? What are the other issues that matter to you?

Send us your comments or questions to AskAmerica@bbc.co.uk and we will respond to what you tell us, as part of our Ask America series, which is a project getting different perspectives from around the country.

We spoke to a rancher who lives on the border and is directly affected by drug smuggling from Mexico. He supports Trump's plan for a border wall.

The Border Ranch: Living on a 'smuggling route'

- Published2 July 2018

- Published25 June 2018

- Published22 June 2018

- Published19 June 2018

- Published25 January 2018

- Published15 January 2018

- Published9 February 2017