A legendary 'mermaid' still swimming at 78

- Published

A tourist destination in Florida has for seven decades wowed audiences with the magic of its mermaid shows. Janine Zeitlin speaks to one of these "legends" who reflects on what the job means to her, and why she still puts on her fins.

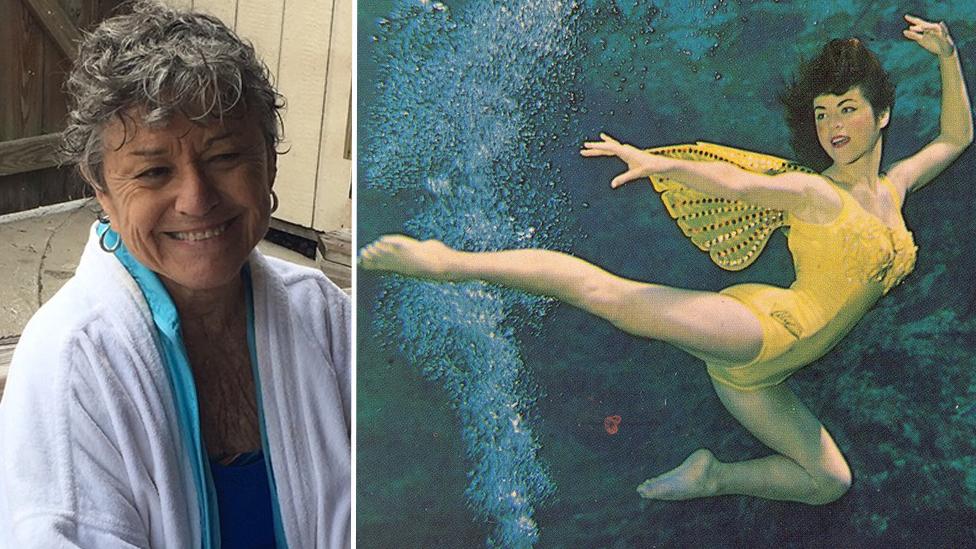

Vicki Smith shrugs off signs near the mermaid dressing room.

Are you show ready? Hair and Makeup.

"I don't wear all the makeup. It doesn't do me any good," says Smith. "I just put on tights and a swimming suit."

Being a 78-year-old mermaid has its perks. She is free of some rules. But her self-deprecation betrays the grace of this great-grandmother with a pixie cut.

Smith is the matriarch of the Legendary Sirens of Weeki Wachee Springs, women in their 60s and 70s who volunteer to perform underwater as mermaids at this iconic central Florida attraction.

All swam here in their younger years. Smith became a mermaid at 17, two days after graduating high school in 1957. Options were limited in the rural surroundings.

"You either went on to college, you got married, or you became a Weeki Wachee mermaid," she says.

Her try-out entailed proving she could swim. She was performing within a month.

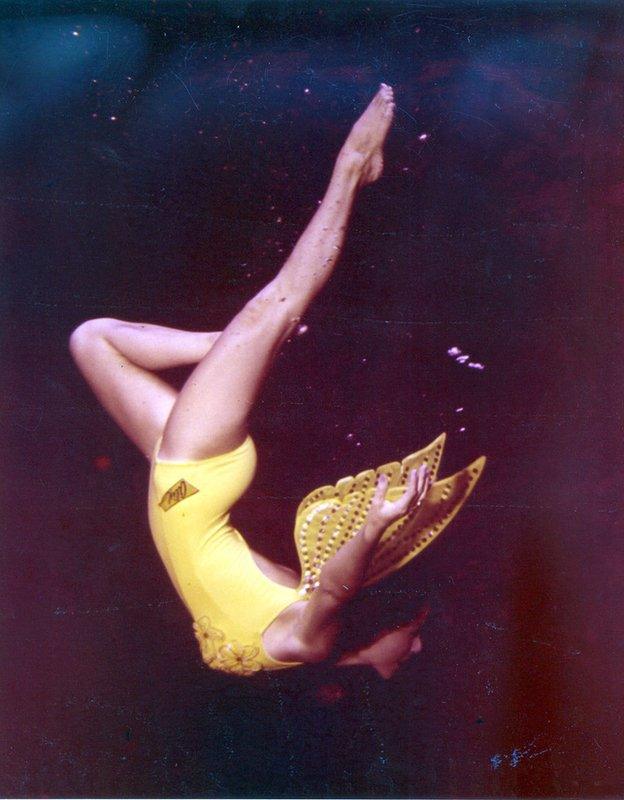

Vicki in her earlier mermaid days

Mermaids now train four to six months before their first show. They receive scuba and lifeguard certifications. Pay wasn't the lure, then or still. Smith made about $3 (£2.30) a show. Current mermaids start at $10 (£7.60) an hour.

Smith's tenure came in a heyday for Weeki Wachee and other Florida springs - they were popular tourist destinations before Walt Disney summoned his kingdom from a swamp.

Early Florida entrepreneurs saw opportunity in the state's plentiful natural springs and added tourist bait.

You might also like

Newton Perry chose mermaids for Weeki Wachee. Perry trained Navy frogmen during World War Two and used his knowledge to create an underwater air hose breathing system, according to the park's history. The underwater mermaid shows began in 1947.

By the 1950s, mermaids swam at sold-out shows. Movie stars visited. In 1959, the American Broadcasting Company bought the spring, added theatrics to the shows, and built the current 400-seat theatre. Smith was there to cut the ribbon.

But in 1961, she gave up the glamour of mermaid life to care for her two children. A few years later, her family relocated to Tennessee.

Her problems disappear under the water, says Vicki

Weeki Wachee beckoned after retirement. She returned to Florida in 1992 to be near her mother. In 2004, Smith joined the Legends, then performing monthly. Weeki Wachee became a state park four years later. Sirens perform less during the summer while they run popular camps for wannabe mer-people.

But they still often perform on holidays and throughout the autumn and winter.

This particular day, July 4, Independence Day, is a busy one. Sirens on the roster are - Bev Sutton, 67, Becky Young, 63, Rita King, 72, and Susie Pennoyer, 64. Some are retired after holding jobs varying from mail carrier to hairdresser to respiratory therapist.

"Vicki is the most inspirational but I believe our whole group is inspirational," says Pennoyer.

Audience members tell them their confidence is catching.

Pennoyer recalls a woman telling her: "I thought I was too fat to wear a bathing suit and you know what? I'm going to the beach next week."

Vicki says it's like a sisterhood

"Are we perfect bodies?" Pennoyer says. "No."

"There's not many people you know in this age range who can do this. Let's face it, there's not many people you know as mermaids anyways."

Pennoyer's eyes well up. Smith rubs her back. The veteran mermaids feel a sisterhood, though it's the spring that compelled their return.

"We call it the magic," Smith says.

Sure, there have been changes, they say - more algae, less sea life and a lower water table, consequences of pollution and development.

Still, the spring is gorgeous. It feels eternal, they say, always the same temperature, 74F (23C) and clear as glass. And though life's trials can pile up with age, the spring erases time and weight.

"The minute you dive in and go under the water, it all disappears," Smith says.

In the water, they are free.

"I can do things in water that I can't do on land. I can do flips, I can do leg lifts. I can touch my toes," Smith says.

She is not immune to terrestrial concerns. Smith's 90-year-old husband Jack has dementia and lives in a care home for veterans.

She visits three to four times a week. He remembers who she is, remembers he's been to shows, but forgets their visits. His fragility makes Smith relish life more.

"There are so many things to get excited about. Sometimes you have to look for them. Sometimes you don't, but you have to be aware that they are there to know."

Her goal is to perform until the age of 80. One siren swam until 79.

Before the noon show, hundreds gather on benches facing glass panels in the chilly sunken theatre. The sirens take the indoor stage in jackets and tights to introduce themselves before the show.

They do this, Smith says, partly to warn the crowd. "If they think they're going to see a bunch of 19-year-olds, they're in for a rude surprise."

A front-row spectator who could not care less about their ages is 33-year-old Rachel Crouch. She beams and pulls her mermaid doll close. Crouch has a developmental disability and is mostly non-verbal, her mother says. She has been counting down the days to the show.

Lights dim. There's an "OH MY GOSH" as the curtain reveals the mighty spring, which releases more than 100 million gallons of water a day. Sirens float from beneath a sandy ledge posed as statuesque ballerinas - backs arched, arms lifted. They sport patriotic one-piece suits. Bouquets of bubbles swirl about. Between gulps from air hoses, they flip into splits.

Later, Smith and two other sirens emerge in cobalt blue mermaid tails to Louis Armstrong's What a Wonderful World. It is one Smith's favourite songs and the tail she feels most beautiful in.

The trio forms a circle, hold hands, and rise.

Yes, the world is wonderful, wonderfully weird. The curtain drops, reminding us that wonders are fleeting, but worthy of chasing.

Janine Zeitlin is a writer based in south Florida