Charlottesville: Why one man is suing Alex Jones for defamation

- Published

Brennan Gilmore: "I became a target, with emailed death threats, harassment, hacking attempts"

Brennan Gilmore heard the car accelerating before he saw it passing just metres in front of him.

The driver of the Dodge Challenger sped downhill to Gilmore's left before pausing, accelerating, then striking dozens of people in a few brief seconds.

The attack by a white supremacist in Charlottesville, Virginia on 12 August last year killed Heather Heyer and injured 19 other people.

Gilmore immediately knew it was not an accident.

Earlier in the day, he had been taking part in counter-protests against white supremacists who had turned out in their hundreds in Charlottesville, ostensibly to protest against the removal of Confederate statues in the city.

He had grown up near Charlottesville, and moved back there having completed 15 years with the US Foreign Service, with whom he had served in the Central African Republic, Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

"As soon as I went downtown I knew Charlottesville had completely transformed," he says of the events on 12 August last year. "I felt that negative charge I had felt before, but over in cities where there was civil unrest, in Africa. It was very strange to feel that in Charlottesville.

"I was taken aback by what I saw and took a lot of photographs to try to document what was going on. It was pretty clear to me it was chaotic and that it was not going to end well."

When the car sped past him, he was prepared, and was already filming.

"The visual was horrifying, the sound of it was revolting," he says. "It was a terrible, terrible moment and all hell broke loose. People were lying in various states of distress, a woman collapsed in front of me.

"Then it occurred to me I had been filming it. I saw I had captured the whole scene. I thought I needed to give this to the police. As soon as I realised what I had, I found a police officer and shared it with her."

The next question Gilmore faced, and one that would shape his life after that day, was whether he should share the clip more widely. He chose to post it on Twitter.

You may find some of the language in the following link offensive

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

He did so partly because family members had told him the crash was being widely reported as an accident.

"I thought it was important to clear up the reasons for what had happened," he says.

"After I had witnessed this, I was worried that things were going to get worse. It was about 2pm and I had a town filled with violent people. I thought that showing it was necessary to tell people in Charlottesville 'stay away, stay home, the stakes are fatal'. I was hoping the city would have a curfew."

His video was quickly picked up by media outlets around the world, and he went on to conduct several interviews.

"It wasn't until a day later that a friend heard about the conspiracy theory, that everything I had seen was a set-up, a propaganda operation."

The claims all centred on Gilmore's activism, and the fact he worked at the time as chief of staff to Tom Perriello, a Democrat candidate for governor of Virginia.

The conspiracy theorists falsely alleged that Gilmore was an agent of the so-called "deep state", who had planned the crash as a way of discrediting President Trump and his supporters. They claimed, again falsely, that he was in the pay of liberal financier George Soros.

The first sign that something was wrong was when Gilmore's sister called him on Sunday 13 August, to let him know that their parents had been 'doxxed' - their address was posted on far-right message boards, and threats were made against them.

With the help of local police, Gilmore tracked down his parents and made sure they were safe. But then, conspiracy-fuelled websites jumped on his story.

"All of the hopes of this being a fringe issue disappeared when Infowars and all these big conspiracy theory-led media picked up on it and shared it out with all their followers," Gilmore says.

"I became a target, with emailed death threats, harassment, hacking attempts on my computer and a bizarre litany of allegations.

"I went through a hellish week of being targeted by these conspiracy theorists. I had friends I'd grown up with who were accusing me."

In the days afterwards, Gilmore decided to defend himself. He published an article in Politico, external headlined 'How I became fake news'.

"Desperate to lay blame on anyone besides the alt-right," he wrote, "they seized on these facts to suggest a counter-narrative to the attack, claiming there was no way that someone with my background just happened to be right there to take the video."

The abuse and threats continued, and Gilmore decided there was one course of action: to sue.

He is taking action against 11 people or companies, external for "defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress", saying articles and videos were posted online "with reckless disregard of the truth".

Among those he is suing are Jim Hoft, the founder of the far-right website Gateway Pundit, and Alex Jones, who set up Infowars. Jones' lawyer did not respond to requests for comment.

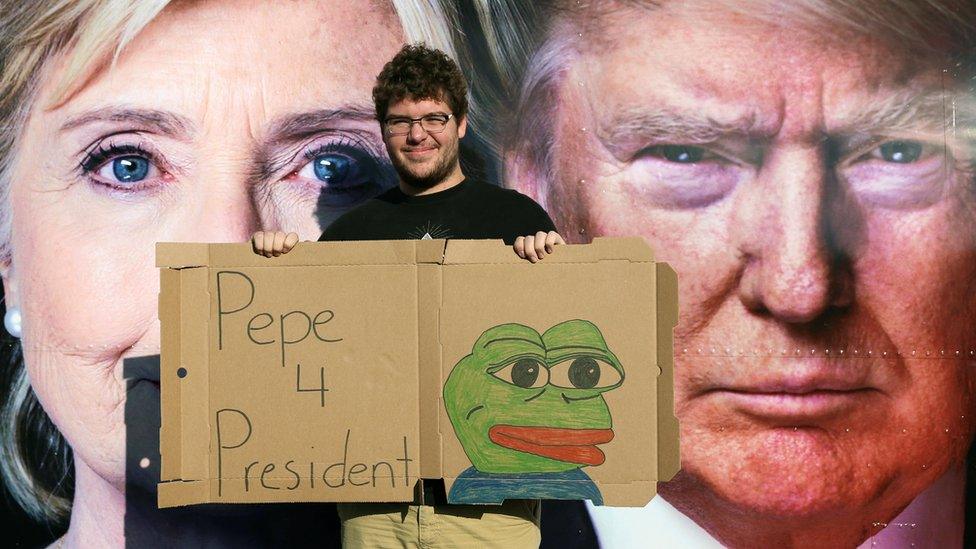

Alex Jones is facing defamation suits on several fronts

The defendants have sought to get the suit dismissed on First Amendment grounds allowing free speech. But in March, the Gateway Pundit doubled down on the allegations against Gilmore, calling him an "unhinged leftie hack" and repeating the claims over which he is suing.

This is not the only case of defamation Jones is facing. Infowars has published stories falsely claiming that the Sandy Hook massacre in Connecticut in 2012 - when gunman Adam Lanza killed 20 children and six adults - was staged.

The relatives of nine victims are now taking action against Jones, saying they have been harassed by people who believe his conspiracy theory.

The Infowars host has sought to get the lawsuit dismissed. This week, a number of tech giants, including YouTube and Facebook, deleted his content, citing hate speech. Twitter, however, said it would not ban Jones.

In November, a district court will hear a motion by Jones and others to dismiss Gilmore's lawsuit. But Gilmore, who now works for a clean energy campaign group, is prepared for a long fight, and he insists he will not settle out of court.

"Compensation for me, people being found guilty, would be setting a precedent and means they won't do it again," he says.

"It will be a long, multi-year case. This case has tapped into a broad feeling that people are disgusted with the tactics of Alex Jones."

- Published9 August 2018

- Published13 August 2017

- Published8 August 2018

- Published7 November 2016