Kavanaugh Supreme Court hearings: Five takeaways

- Published

While much of official Washington was obsessing over Bob Woodward's White House expose and the authorship of the anti-Trump internal "resistance" essay in the New York Times, Brett Kavanaugh's nomination for the US Supreme Court slowly rolled along.

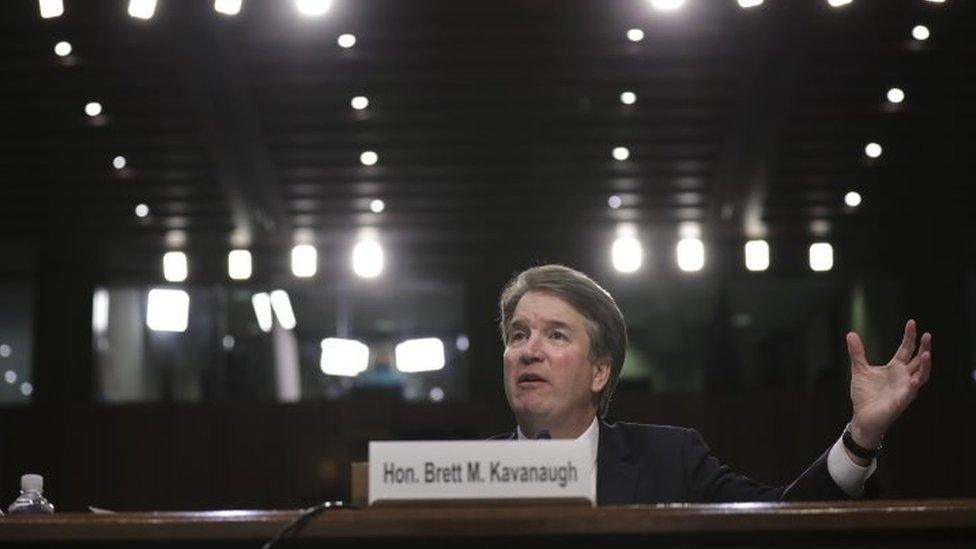

Over the course of four days the Senate Judiciary Committee held confirmation hearings during which politicians postured for the cameras and questioned the man who would replace Justice Anthony Kennedy on the highest court in the US.

Mr Kavanaugh, currently a federal appellate court judge based in Washington, DC, is by all accounts a reliable conservative. By replacing Mr Kennedy, who occasionally sided with the four liberal justices on issues like abortion, the death penalty and gay rights - his presence on the bench would almost certainly move the nine-member court to the right.

Given these court nominations are lifetime appointments, the stakes are high.

For the past 30 years - since the Supreme Court hopes of Robert Bork, nominated by Ronald Reagan, foundered due to the judge's controversial conservative legal writings and speeches - confirmation hearings have followed a predictable, scripted path.

Senators from the opposing party attempt to pin down a nominee on hot-button political and legal issues that could make them less palatable to moderate senators and the public at large, while the would-be justice tries to be as vague and uncontroversial as possible.

Nominees express an unwillingness to pre-judge future cases and, as current Chief Justice John Roberts said during his hearings in 2005, assert that they are like impartial baseball umpires, calling "balls and strikes" based on fixed, unyielding rules.

During this week, Mr Kavanaugh - dancing away from what he said were hypothetical questions - demonstrated that he knew this particular bit of political kabuki theatre well.

What made these confirmation hearings different and more heated, however, was the extensive government paper trail the nominee has left, and the fact that many of the documents connected to Mr Kavanaugh from his years in the George W Bush administration have been shielded from Senate Democrats and the public.

The document war

Back before Mr Trump tabbed Mr Kavanaugh for the Supreme Court, Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell reportedly warned the White House that his record as White House staff secretary and a senior adviser to Mr Bush would be a headache for Republicans.

He was right.

The opening gavel of the hearings was still ringing in the air when Democrats began objecting to the tardiness with which papers were being turned over to them, the process with which they were being reviewed (by a Bush-era Republican official) and the fact that more than 90% of the documents were being withheld.

Democratic Senators Cory Booker (L) and Kamala Harris (R) repeatedly objected to Mr Kavanaugh's hearing

By day three, Democrats - led by New Jersey Senator Cory Booker - had started unilaterally releasing some Kavanaugh emails previously kept from public view. It prompted a heated debate about whether they were violating Senate rules or engaging in a publicity stunt over already cleared material.

Democrats alleged Republicans - and Mr Kavanaugh - were hiding embarrassing documents. And, in some cases, the information revealed clues about the nominee's views that went beyond what he was willing to concede under committee questioning.

They suggested that the records called into question Mr Kavanaugh's testimony before the committee in 2006, when as an appellate-court nominee, he said he had little involvement in Bush administration deliberations on terrorist interrogation programmes and several other at-the-time controversial political matters.

Some on the left have gone so far as to call for Mr Kavanaugh to be referred to the Justice Department for investigation into whether he lied to Congress.

Abortion clues

Perhaps the most closely scrutinised issue during the Kavanaugh hearings has been the nominee's position on Roe v Wade, the landmark 1973 court decision legalising abortion across the US. When pressed, he said it was an established precedent that had been subsequently reaffirmed by the court - "precedent upon precedent".

Pro-choice supporters surely cringed, however, when they read Mr Kavanaugh's use of the term "abortion on demand" in a 2017 appeals court decision - language frequently employed by more strident anti-abortion activists.

Women dressed as Handmaids from the television series The Handmaid's Tale protest abortion rights outside the hearing

In addition, Democrats pointed to a 2003 email written by Mr Kavanaugh in which he objected to an administration-backed newspaper essay that called Roe v Wade the "settled law of the land".

Mr Kavanaugh said he was merely noting what some legal scholars believed. Committee Democrats weren't buying it.

"Now that the American people know what we know," California Democrat Kamala Harris tweeted., external "We have every reason to believe Kavanaugh will overturn Roe v Wade."

Prosecuting the president

Shortly after the president announced Mr Kavanaugh's nomination, many critics turned their attention to a 2009 law review article written by the judge questioning whether a sitting president can be subjected to criminal prosecution.

Given the various controversies swirling around the current occupant of the White House, senators this week pushed Mr Kavanaugh's for his views on the matter.

For the most part, he demurred. "No president is above the law," he said.

He added that his article was only a suggestion that Congress consider writing presidential immunity into law and it was "not my constitutional views".

Mr Kavanaugh said he wouldn't consider recusing himself from ruling on legal issues involving the president who nominated him.

"I promise you that I have an open mind," he said.

Gay rights at risk?

Justice Anthony Kennedy was widely considered to be the champion of gay rights on the Supreme Court. He wrote a number of landmark decisions on the subject, including the 2003 decision in Lawrence v Texas striking down a state law banning gay sex and the historic 2015 Obergefell v Hodges, which legalised same-sex marriage across the US.

Given that Mr Kavanaugh is poised to take Mr Kennedy's seat on the court, his views on the issue were repeatedly front and centre during the confirmation hearings. His answers, however, have some gay rights activists concerned.

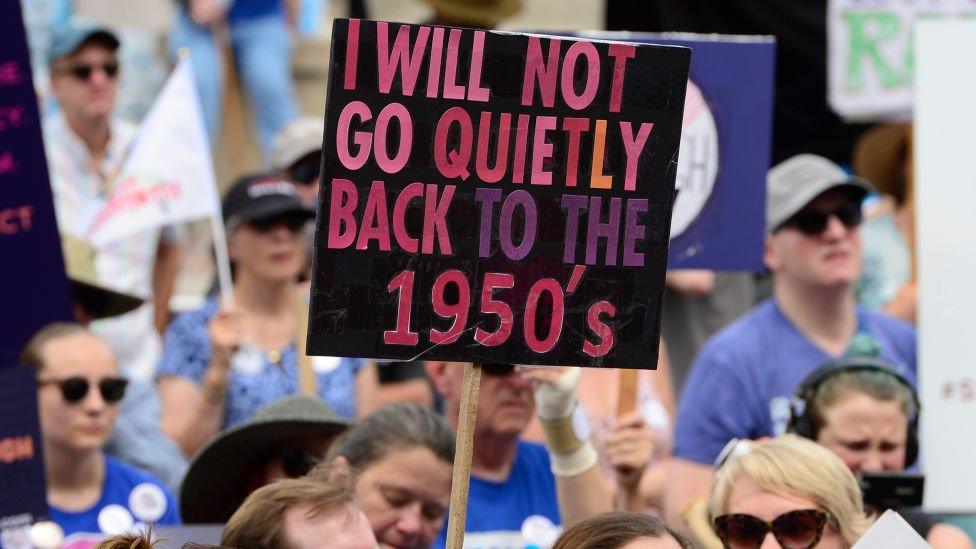

Protesters against Mr Kavanaugh's nomination earlier in August

When Ms Harris asked Mr Kavanaugh if he thought Obergefell was correctly decided, for instance, he declined to answer. Critics pounced, noting that when it came to other landmark cases, like the 1954 Brown v Board of Education ruling against racial segregation in public schools, Mr Kavanaugh was more forthcoming.

"If Kavanaugh could say Brown v Board was one of the greatest moments in [Supreme Court} history," tweeted liberal commentator Maya Harris, external, "why won't he say Obergefell, which established LGBT marriage equality, was one of the great moments in the court's history?"

Instead, Mr Kavanaugh pointed to this year's Masterpiece Cakeshop v Colorado Civil Rights Commission decision, which - while reaffirming that the "days of discriminating against gay and lesbian Americans as inferior in dignity and worth are over" - did so as part of a ruling that was sympathetic to a man who would not bake a wedding cake for a gay marriage.

The emphasis on religious liberty will surely please the president and evangelical activists, but it will also set off warning alarms for gay-rights supporters.

Mr Kavanaugh's glide path

This week's hearings may not have gone as smoothly as Mr Kavanaugh and the White House would have liked. The reality, however, is the judge's nomination is still headed for a successful conclusion because of simple math.

There are 51 Republicans in the Senate. If 50 vote in favour of Mr Kavanaugh's confirmation, he'll have his lifetime appointment to the court without the need for Democratic support. Even with questions surrounding the judge's views on abortion - a point of particular interest for some pro-choice Republican senators - it appears that the party's battle lines are holding.

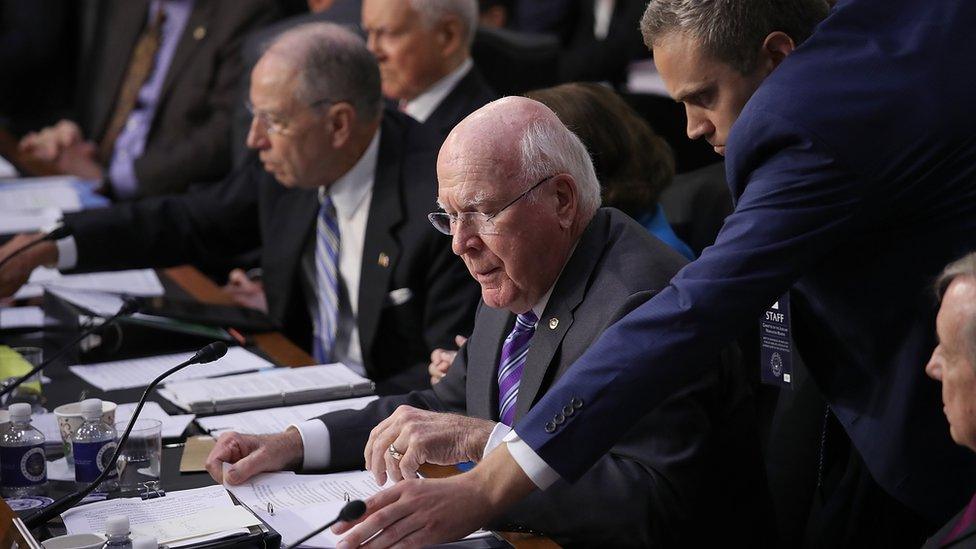

Senator Patrick Leahy was among those who pressed Mr Kavanaugh

Democrats, including those like Mr Booker and Ms Harris with 2020 presidential aspirations, will continue to press in the committee room and on the floor of the Senate, hoping to exploit any weaknesses.

In a different era, they may have had a reasonable chance of success. That's not how the confirmation process works these days, however.

When it comes to the Supreme Court, which has become the final arbiter in some of the most contentious political and cultural battles of our time, the stakes are too high for a party to risk failure.

- Published4 September 2018

- Published10 July 2018

- Published4 September 2018