Four ways US mid-terms are undemocratic

- Published

The mid-term elections are being held up as a key barometer of support for Donald Trump's presidency. But how representative of the US are they really?

If Democrats sweep to power in Congress, it will be seen as a rebuke of the Trump government.

If the Republicans prevail, the message will be that the nation has validated his stunning 2016 victory.

Yet in a country of nearly 326 million, perhaps only 100 million ballots will be cast.

The United States is a representative democracy. At times, however, the process for determining control of the federal government can appear very undemocratic.

Here are some reasons why.

Low turnout

If mid-term elections are less than fully representative of the popular will, the American public - first and foremost - has itself to blame.

A majority of citizens who are eligible to vote simply choose not to.

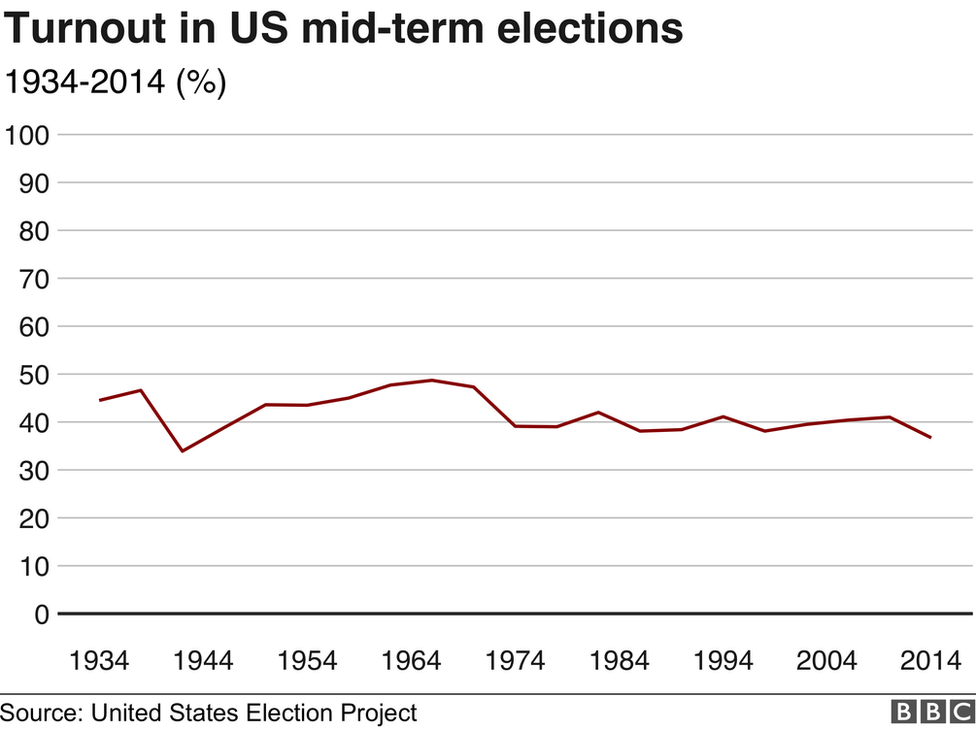

In the 2014 mid-term elections, only 35.9% of the voting-eligible population cast a ballot. That was the lowest mark since 1942. The modern peak was in 1966, when 48.7% turned out - still less than half.

In the 1970s, the numbers took a precipitous decline - a consequence of the Watergate political scandal, perhaps - and they largely held steady until its most recent low point.

Presidential election years are somewhat better, which is not entirely surprising given the vast sums of money spent on advertising and the non-stop media attention.

The peak was 64% in 1960, and after a drop through the 1970s and 1980s, the numbers rose again, to 62% in Barack Obama's historic 2008 election and 60% in 2016.

Even in the 2016 presidential election, however, a Pew Research Center report, external found that the US turnout levels ranked 31 out of 35 democratic nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Some of this lack of enthusiasm to vote can be ascribed to the relative non-competitiveness of many of the congressional races, where incumbent politicians frequently win more than 90% of the time.

Voter suppression

In a number of states, legislatures have made it more difficult to register to vote and cast ballots. Supporters explain that the actions are intended to combat voter fraud, although they are frequently hard-pressed to come up with tangible evidence of widespread malfeasance.

Voters in eight states must present government-issued photo identification in order to cast a non-provisional ballot. Another eight states prefer that voters have photo identification, but they accept other methods of verifying identity.

Voters in Arlington, Virginia

When combined with the difficulty some - particularly the poor, the elderly and minority communities - have with getting proper government identification, the impact can be substantial.

According to a University of Wisconsin study, external, in 2016 at least 17,000 voters in Wisconsin were deterred from casting ballots during the presidential election because they lacked acceptable photo identification. Mr Trump only won the state by 22,700 votes.

Some states have also ramped up efforts to purge their voter rolls, which frequently contain inaccuracies because individuals die or move to other precincts without informing their local election board (although there is little evidence that those inaccuracies lead to widespread illegal voting).

The move to trim the lists has been particularly pronounced in the nine states (mostly in the South) that, because of their history of racial discrimination, had until a 2013 Supreme Court decision been required to obtain federal pre-approval for any changes in their voting process.

According to a report by the Brennan Center, left-leaning think tank, 12 million voters nationwide were removed from state rolls from 2006-08. From 2012-14, that number increased to 16 million. The centre attributed half of that rise - 2 million voters removed - to the actions in states covered by the Supreme Court decision.

Georgia recently ignited a firestorm of controversy because it quietly tried to close seven of the nine polling places in a part of the state with a large population of low-income black residents.

Gerrymandering

In 37 states, the boundaries of voting districts - for members of the US House of Representatives as well as state legislatures - are determined by state politicians. That creates a built-in incentive to draw lines that maximise the political advantage for the party in control, giving their side greater representation than would be indicated by a straight distribution of the vote statewide.

It's a power legislators regularly exercise.

Two common strategies for partisan-inclined map-makers are to "crack" opposition voters into multiple districts to dilute their numbers or "pack" them all into one constituency. With computer-assisted statistic modelling, what used to be sometimes haphazard attempts to "gerrymander", as it is called, has become an exacting science.

Why are US election campaigns never-ending? Ask America has the answer

In the Wisconsin state assembly races in 2012, for instance, Republicans won 60 out of 99 seats (60%) despite winning only 48.6% of the state-wide vote. Democrats have produced similar advantages in states like Maryland.

The Wisconsin map became the basis for a lawsuit by Democratic voters and officeholders alleging that it amounted to an unconstitutional infringement on their constitutionally protected voting rights. But while the US Supreme Court has ruled it illegal for legislatures to use line-drawing to diminish the power of minority voters, it declined to strike down the Wisconsin maps for political bias.

California is among a handful of states that have handed their map-drawing authority over to independent commissions. In others, such as Pennsylvania, state courts have ruled partisan gerrymandering violates state laws.

Even with explicit prohibitions on the most glaring forms of gerrymandering, however, imbalances can be difficult to avoid. Republicans nationally have a built-in advantage in the House of Representatives due to simple demographics. Their voters tend to be more spread out across the country, while Democratic voters congregate in larger urban areas.

In 2016, because of the byzantine machinations of the Electoral College, Donald Trump became president despite losing the nationwide popular vote by nearly 3 million.

The Senate map

Mid-term elections don't fully reflect the will of the people for another fundamental reason. It's the way the nation's founders wanted it.

The two-chambered Congress, with a House of Representatives and a Senate, was a result of the "Great Compromise" between the large and small states during the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Seats in the House of Representatives are determined by proportional representation, but every state has equal influence in the Senate.

As the US has grown, the contrast has become particularly stark. California's 40 million residents, for instance, elect 53 members of its House delegation, while the entirety of Wyoming, population 579,000, has one. Both states, however, have two seats in the Senate.

Then there are the residents of US territories like Puerto Rico and Guam, as well as the District of Columbia (with a population by itself greater than Wyoming's), who have no congressional representation.

While the entire membership of the House of Representatives stand for election every two years, the framers of the constitution designed the Senate to be less responsive to popular will. Members of the upper chamber of Congress serve six-year terms, staggered so only one-third of the 100-seat body comes up at a time.

In an apocryphal story, George Washington once explained to Thomas Jefferson that the Senate was like a saucer into which the hot tea of the House could be poured to cool. In fact, the Senate was once even less democratic than it is now. Prior to a 1913 constitutional amendment, senators were chosen by state legislators, not American voters.

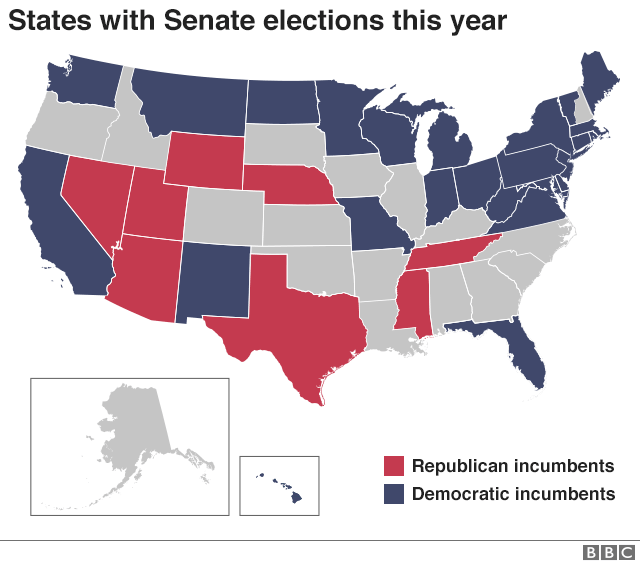

This year, thanks to special elections, 35 Senate seats are up for a vote. Of that number, Democrats (and Democratic-friendly independents) are defending 26 of them - including 10 in states Mr Trump won in 2016.

The reality, then, is that while the political winds could be blowing strongly to the left, the Republican Party still has an opportunity to hold - or gain - ground in the chamber that has the sole power to confirm executive and judicial appointments and ratify international treaties.

Residents of 17 states will be sitting on the sidelines for one of the most meaningful political battles of the year. And in the states that do cast ballots, some voters will have more of a say in the outcome than others.

November could very well become an inflection point in Donald Trump's presidency. If it is, however, it will be a result of the voices of a minority of Americans being heard.